Table of Contents

ALSO BY BEN YAGODA

When You Catch an Adjective, Kill It:

The Parts of Speech, for Better and/or Worse

The Sound on the Page: Style and Voice in Writing

About Town: The New Yorker and the World It Made

Will Rogers: A Biography

The Art of Fact: A Historical Anthology of Literary Journalism (coeditor)

All in a Lifetime: An Autobiography (with Ruth Westheimer)

To Gigi

Authors Note

BY WAY OF DEFINITION

IN THIS BOOK I USE THE WORDS memoir and autobiographyand, on occasion, memoirsto mean more or less the same thing: a book understood by its author, its publisher, and its readers to be a factual account of the authors life. (The one clear difference is that while autobiography or memoirs usually cover the full span of that life, memoir has been used by books that cover the entirety or some portion of it.) Therefore, the following autobiographical works are not considered: diaries, collections of letters, autobiographical novels, and, for the most part, any unpublished text.

My interchanging of the terms may seem odd, since in (very) recent years, the years of This Boys Life and The Liars Club and Running with Scissors, memoir has acquired a distinctive sense. A brief stroll through the history of the words may clarify things. Autobiography is unambiguous. It was first used in 1809 and within a couple of decades acquired its current meaning: a biography of a person written by that person. (A fuller account of the origin of the word is in chapter 3.) Memoirs and memoir, both of which are derived from the French mmoire, or memory, are more complicated. The plural form was and is synonymous with autobiography; the Oxford English Dictionary cites William Wycherley, who in 1678 referred to a volume entire to give the world your memoirs, or life at large. Memoirs is still in use and is often chosen by statesmen and other eminencesor, as a result, is used ironically, as in Albert Nocks Memoirs of a Superfluous Man (1943) and Bernard Wolfes Memoirs of a Not Altogether Shy Pornographer (1972).

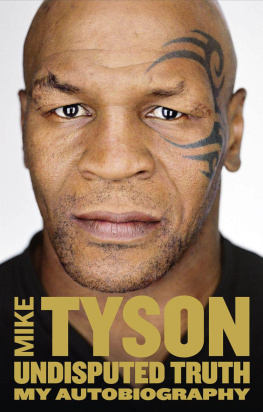

Roy Pascal, in his 1960 book Design and Truth in Autobiography, succinctly laid out the traditional contrast between autobiography and s-less memoir: In the autobiography proper, attention is focused on the self, in the memoir or reminiscence on others. A well-known, fairly recent example of the latter would be A. E. Hotchners 1966 Papa Hemingway: A Personal Memoir, in which Hotchner is a supporting player and Hemingway the star. That distinction still held sway as late as 1984, when another scholar, Richard Coe, observed that while in an autobiography it is the writer himself who is the center of interest, in a memoir the writer is, as a character, essentially negative, or at least neutral.

In France, at least, there was also a distinction among the forms in their respective requirements for accuracy and truthfulness. In 1876, Louis-Gustave Vapereau wrote in the Dictionnaire universel des littratures: Autobiography leaves a lot of room to fantasy, and the one who is writing is not at all obliged to be exact about the facts, as in memoirs.

The twenty-first-century memoir, of course, is 180 degrees different. Attention is resolutely focused on the self, and a certain leeway or looseness with the facts is expected. (The gross liberties or outright fabrications perpetrated by James Frey and many other recent fraudulent memoirists are another matter, and will be considered at length in the pages that follow.) Writing in his 1996 memoir Palimpsest, Gore Vidal reversed Vapereaus classifications: A memoir is how one remembers ones own life, while an autobiography is history, requiring research, dates, facts, double-checked. Another recent memoirist, Nancy Miller, was hardly going out on a limb in describing her possible strategies for writing about an event in her past: I could write down what I remembered; or I could craft a memoir. One might be the truth; the other, a good story.... When I sit down to reconstruct my past, I call on memory, but when memory fails, I let language lead.... As a writer, the answer to the question of what really happened is literaryor at least textual. I will know it when I write it. When I write it, the truth will lie in the writing. But the writing may not be the truth; it may only look like it. To me. Among other things, this book will try to explain how and why the change took place.

My main approach in seeking the answers to these and other questions is not thematic, theoretical, generic, psychological, moral, or aesthetic, but historical. That is, Rousseaus Confessions makes sense only if the earlier tradition of spiritual autobiography is considered, and Frank Conroys Stop-Time makes sense only in the context of Rousseaus Confessions. A historical frame of mind is helpful, as well, in corralling the tens of thousands of autobiographies that have been written since the dawn of time into a manageable, useful, and readable narrative. There is no room to consider every memoir, a majority of memoirs, or even a majority of great memoirs. (And that is why such exceptional works as Vladimir Nabokovs Speak, Memory, Mary McCarthys Memories of a Catholic Girlhood, and Saul Friedlanders When Memory Comes, among many others, wont be discussed here.) Pride of place goes to books that memorably or notably did a significant thing first, and thus changed the way the genre was conceived.

Chapter 1

MEMOIR

UNIVERSE

As mankind matures, as it becomes more possible to be frank in the scrutiny of the self and others and in the publication of ones findings, biography and autobiography will take the place of fiction for the investigation and discussion of character.

H. G. WELLS, Experiment in Autobiography, 1934

I moved on to the memoir section. After browsing for a while, I knew

why it had to be so big: who knew there was so much truth to be told,

so many lessons to teach and learn? Who knew that there were so

many people with so many necessary things to say about themselves?

I flipped through the sexual abuse memoirs, sexual conquest memoirs,

sexual inadequacy memoirs, alternative sexual memoirs, remorseful

hedonist rock star memoirs, twelve-step memoirs, memoirs about

reading (A Reading Life: Book by Book). There were five memoirs by

one author, a woman who had written a memoir about her troubled

relationship with her famous fiction-writer father; a memoir about her

troubled relationship with her children; a memoir about her troubled

relationship with the bottle; and finally a memoir about her more

loving relationship with herself. There were several memoirs about the

difficulty of writing memoirs, and even a handful of how-to-write

memoir memoirs: A Memoirists Guide to Writing Your Memoir and

the like. All of this made me feel better about myself, and I was

grateful to the books for teaching mewithout my even having to

UNIVERSE

UNIVERSE