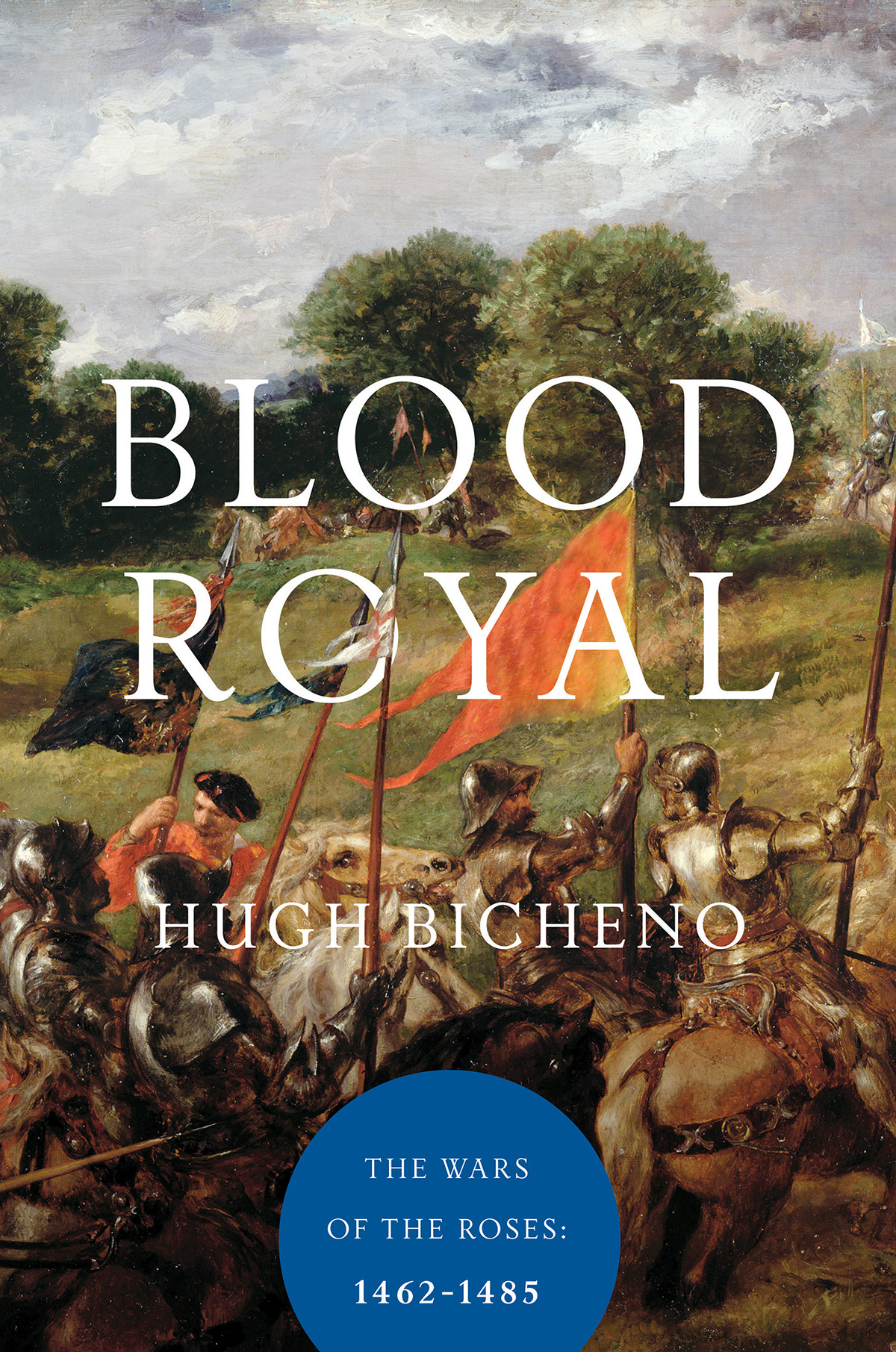

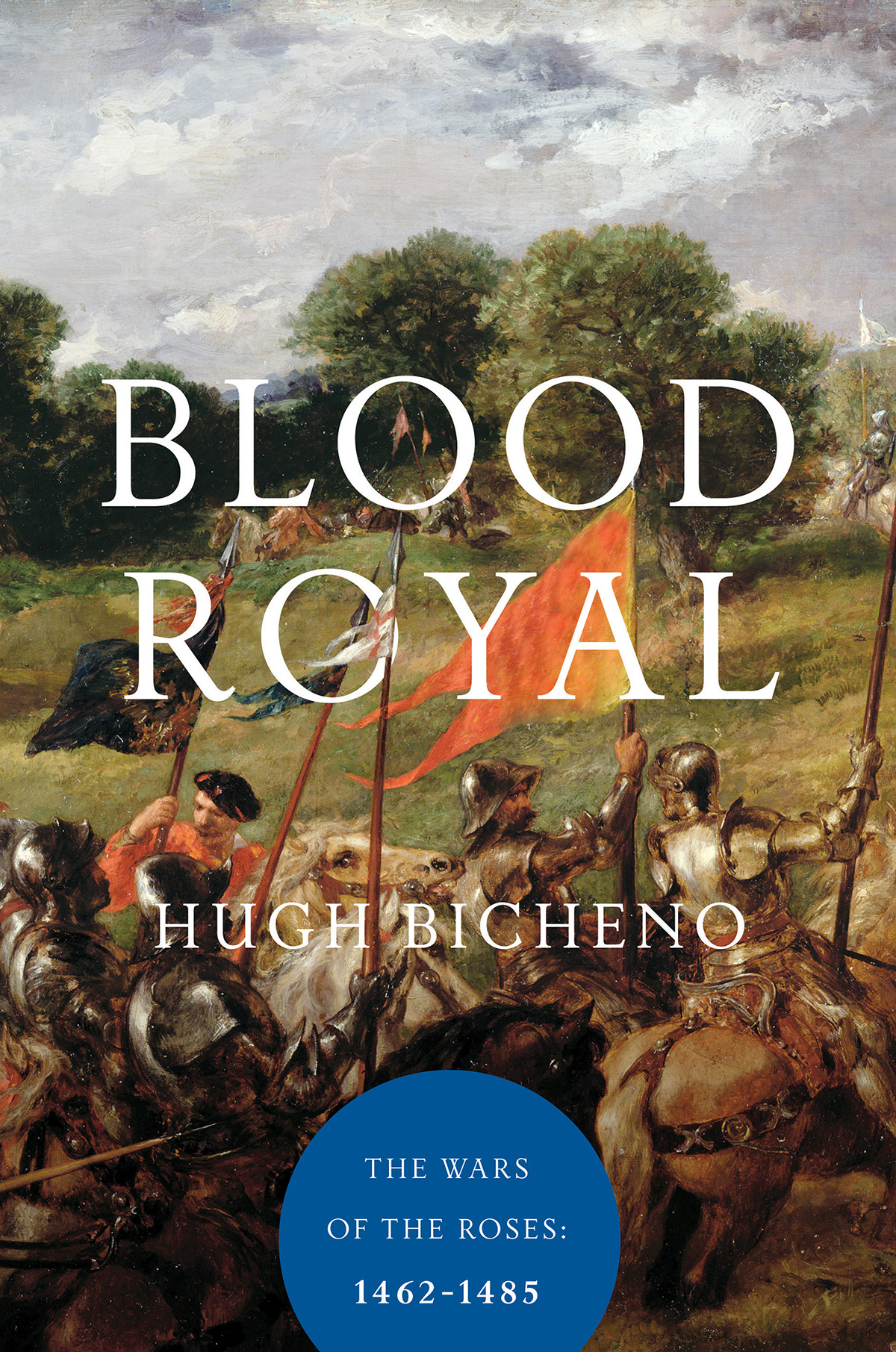

BLOOD

ROYAL

THE WARS OF THE ROSES: 14621485

HUGH BICHENO

PEGASUS BOOKS

NEW YORK LONDON

BLOOD ROYAL

Pegasus Books Ltd

148 West 37th Street, 13th Floor

New York, NY 10018

Copyright 2017 by Hugh Bicheno

First Pegasus Books hardcover edition June 2017

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in whole

or in part without written permission from the publisher, except by reviewers who may

quote brief excerpts in connection with a review in a newspaper, magazine, or electronic

publication; nor may any part of this book be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system,

or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying,

recording, or other, without written permission from the publisher.

ISBN: 978-1-68177-428-2

ISBN: 978-1-68177-483-1 (e-book)

Distributed by W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

For

JACK and ISABELLA

SEBASTIAN and RUAN

My Hearts Delight

I T WOULD BE ANTICLIMACTIC TO EXTEND THE WARS OF the Roses narrative beyond Bosworth. There were several rebellions against the Tudor succession, including one by Thomas Vaughan in 1486, crushed with relish by Rhys ap Thomas, and two in 1487 and 1497 led by Yorkist impostors sponsored by Margaret of York, dowager Duchess of Burgundy. During the first John de la Pole, Earl of Lincoln and Richard IIIs heir presumptive, was killed.

Although Henry VII claimed the throne by right of conquest, he was finally provoked into crushing the Yorkist seed. He executed Clarences feeble-minded and blameless son Edward, Earl of Warwick, in 1499. Emperor Maximilian surrendered John de la Poles rebellious brother Edmund to Henry, under oath not to harm him. Previously demoted from duke to earl of Suffolk and then deprived of the earldom, Edmund was executed by Henry VIII in 1513. Richard de la Pole, the last Yorkist pretender, was killed in 1525 fighting for France in Italy.

Edward Gibbon observed that history is little more than the register of the crimes, follies, and misfortunes of mankind, hardly the stuff of comedy. Although the doings of our ancestors were often farcically inept, an awareness of our own on-going stupidities generally constrains our urge to laugh at them. Happily we need feel less inhibited when to bowdlerize T. H. Huxley a fanatically held belief is slain by an ugly fact.

Just such a moment occurred when, thanks to the persistence and brilliant deduction from sparse facts of Philippa Langley, a devoted Ricardian, the remains of Richard III were discovered and their identity confirmed by mitochondrial DNA. Unfortunately the bones revealed that he was, after all, the deformed individual portrayed by Shakespeare in The Tragedy of King Richard the Third.

The discovery undermines the defining purpose of the Richard III Foundation, which is to challenge the popular view of King Richard III by demonstrating through rigorous scholarship that the facts of Richards life and reign are in stark contrast to the Shakespearian caricature. It is going to be harder to defend that thesis now we know that the most salient characteristic of Shakespeares Richard III was not, in fact, a caricature.

The modern Ricardian movement is the historiographical oak that sprang up from the acorn planted by Josephine Teys 1951 detective story The Daughter of Time and a sixteenth-century portrait of Richard that portrays him as a sensitive soul. I could not have written these books without the vast amount of excellent scholarship the movement has generated. However the defining Ricardian dogma that Richard IIIs black villainy was an invention of Tudor propagandists was always skating on thin ice.

The key contemporary sources for the events of 1483, by which Richard III is rightly judged, are the Crowland Continuator and Mancini. The first was unknown to a wider audience until the end of the Tudor period, and the second not until 1934. As the editors of the Crowland Chronicle Continuations judiciously observe, this helps to explain why Tudor propaganda was so successful: like all good propaganda it offered an interpretation which even informed people, in independent possession of the facts, could accept.

No serious historian doubts that Richard was directly responsible for the murder of his nephews, and that it was the defining act of his life and reign. Despite this, we saw the strength of the Ricardian cult in the veneration surrounding the reburial of his remains in March 2015. As Thomas Cromwell said to Ambassador Chapuys, Richard was a bad man who met the end he deserved; that Cromwells master Henry VIII was also loathsome does not alter the justice of that verdict. It is far more debatable whether Richard deserved a handsome tomb monument in Leicester Cathedral with Loyaulte me lie inscribed without irony on the plinth.

It was, however, perfectly expressive of the Zeitgeist. If a latter-day Richard III were put on trial today for murdering his nephews in order to steal their inheritance, well-paid apologists would be lining up to argue in mitigation not only that his intentions were good, but also that he was not responsible for his actions because of his congenital deformity and malignant upbringing. They would also, of course, assert that society, not he, was to blame.

It should go without saying that Richards personality was shaped by his genetic endowment, his dysfunctional family and the violent social environment in which he grew up. But while such influences predispose to psychopathy, they are not predictive. He was also immensely privileged and raised in the Christian chivalric tradition, which did not constrain him in the slightest. Only his elevated social status differentiates him from common criminals.

If the Tudor big lie turns out not to be so big after all, the same cannot be said for other black holes in the historiography of the Wars of the Roses. In Battle Royal it was the demonization of Marguerite dAnjou for having fought for her sons birthright, and in Blood Royal it has been the greedy-and-grasping-parvenu Woodvilles trope. These influential interpretations have scant basis in fact and are little more than manifestations of the universal human tendency to blame the foreigner, of a startling amount of misogyny, and of petty bourgeois snobbery.

In Darwinian terms the final verdict on the Houses of York and Neville, who have dominated our narrative, is that even their mitochondrial DNA will be extinguished upon the death of the childless donor who provided the sample that permitted the identification of Richards remains. By contrast, a fair proportion of the native English population, including the monarchy and much of the old aristocracy, carries the mitochondrial DNA of Jacquetta de Luxembourg, wife of murdered Richard Woodville, mother of Queen Elizabeth and of murdered Anthony and John, and grandmother of the little boys murdered in the Tower of London.

If, as Darwinian absolutists argue, human beings are simply DNAs means of reproduction, then the winners rosette in the competition among the bloodlines of senior titles of aristocracy goes to John Howard. Despite vicissitudes including two subsequent attainders under Henry VIII and Elizabeth I and a genetic bottleneck in 1975, his linear descendant is Edward William Fitzalan-Howard, since 2002 not merely the 18th Duke of Norfolk and Earl Marshal of England, but also Earl of Arundel (with Jacquettas DNA along for the ride), of Surrey and of Norfolk, and Baron Maltravers, Beaumont and Howard of Glossop.

Next page