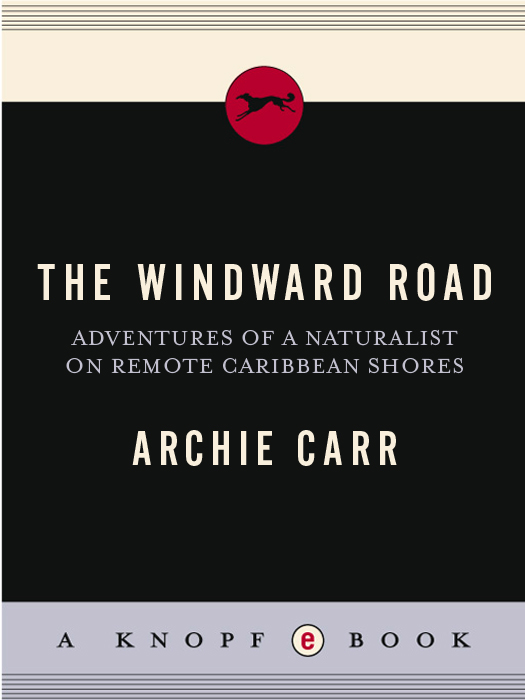

L. C. catalog card number: 559277 Archie Carr, 1955

Copyright 1955 by ARCHIE CARR . All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages and reproduce not more than three illustrations in a review to be printed in a magazine or newspaper. Published simultaneously in Canada by McClelland & Stewart Limited. Manufactured in the United States of America.

The lines from Kitch on are by Aldwyn Roberts (Lord Kitchener) and are reprinted with the kind permission of the Mechanical-Copyright Protection Society Limited.

eISBN: 978-0-307-83211-5

v3.1

TO THE MEMORY OF

Thomas Barbour

Preface

D OWN IN the Caribbean the trade wind blows so honestly that in some of the islands you rarely hear the cardinal directions used, but people speak instead of living to leeward or of going to windward to visit an aunt. On all but the smallest or most rugged or least populated islands there are roads that lead to or run along the upwind coasts, and these are known as windward roads. I got to thinking in these terms and liked it, and then it occurred to me that the book I was writing grew mostly out of the hundreds of miles I had walked along the beaches of the Caribbean, where the good beaches are the windward ones built up high and clean by the driven surf. These beaches were the road I walked, and it is a good road. If you are in the tropics and have trouble seeing the good in where you are, work your way to windward where the trade comes in to land.

Leave your car at Maracas Bay, say, in northwestern Trinidad, and walk off into the marvel of the land-edge there; or travel the heights of north-coast Jamaica, past scenes I never believed in the old stereopticon days. Follow the windward road in Tobago from Scarborough to Speyside, through the West Indies as they used to be, and if the sea is not angry, take a boat out to Little Tobago and look for the birds of paradise there. Go west out of Havana, turn into the wind to Baracoa, and stop at the little restaurant by the inlet for rabirrubias panbroiled in olive oil, and find the part of town where little houses have clear pools hewn out of the rock of the yards and loggerheads living there, with the people, like confident hens. Get out of Puerto Limn in Costa Rica and climb the stacks and spurs to search out the slips of palm-edged beach set like jewels among the tall rocks.

Or on Grand Caymanif it is July and the broad scrub inside the island claws down the breeze before it gets to Georgetown and looses the mosquitoes in the shade and leaves the open land in the hard grip of the sun, and it is no longer a pleasant place to be, there in the lee of the landtake the road to windward and see the change.

Take a taxi for it. George Potter has one and there is another driven by a blonde woman named Honeysuckle. Flip a coin and say it comes out George. His wife just got back from the Bay Islands on the Cacique, and it was one long storm the whole way home and they threw out the cookstove to ease the little ship. George will want to take his wife alonghe wont say to keep her in reach, but that is what he means. And then the young will set up a dinning to go, and you wind up sharing the car with a family of six. But they are all cheerful and none of them minds the crowding.

Now take it easy. You have a goal in mindto get coolbut keep it in the background till you can do something about it. Forget the solid heat and take the quiet charm of this place so few outsiders ever see. You have to take itnobody is going to sell it to you. Nobody tries to sell you anything in Grand Cayman.

So, stop twice before you ever leave the Iron Shore, as they call the rust-brown fossil reef of the downwind edge of the island. Stop first by the graveyard, where the sea sucks and bulges in a little tank cut out of the rock, and fish up the chicken hawksbills they keep there and hold them in the sun and see how you have to turn your eyes away from the five-colored fire from their rayed shells. Stop again to see how the old Cayman glory grew, how the old tradition hangs by a thread in the little shipyard, in the strong slim sculpturing of a mahogany hull. Look hard, because it is the last of something great.

Then start the seven-mile drive to windward, but keep your pace down, and when you hear the hoot of a blown conch, stop for an image to take away, when a bicycle crunches by on the white rock road, pedaled by a gangling tan man with long bare feet and a wide straw hat, who raises the shell twice a minute and blows one long note to cry the conchs and goatfish in his saddle basket. It is that sort of thing you will see if you are willing; and the little store beside the incandescent road out where the town wanes, with the chalked sign in big letters like train-times at the depot, and the sign says:

Just arrive Sweet potatoes

Skellion

Fresh bullas

Chochoes

Cocoes |

When you get there, dont just go on bymake the Potters stop and tell you what just arrived. They will enjoy the trip a lot more for it.

Then when you are still hardly under way, ask George which house belongs to Rosabelle Byrd, whom they call the best cook in Georgetown, which is saying a great deal. When he points out the gnome-hut, the only one nearby with a thatch roof, go in and tell Rosabelle you always liked to eat, and hide the wince when she pokes you in the ribs for love of you, and listen to what she says about Cayman fish stew, which is what happens to bouillabaisse in the islands, or about codfish-and-akees or black crab stuffed, or the things they do with green turtles to make Caymanians strong and unafraid of the sea. Get a firm commitment for her to cook you a meal and then head on into the rain-hungry island, and after a while come out on the windward shore. You see it first in the streaming trees, and then the live air is in your face and you see the waves of the upwind ocean and some old stone walls where hurricanes scattered a settlement ages past, and you say this is the place. You get out there and ask George whether he will wait for you or come back, but he is already necking and the kids are chasing crabs and you leave them alone. It is the windward shore you are on now and the burden of leeward heat is gone, the trade wind tilts the slack feathers of the long, black smooth-billed anis in the bushes, and only the rocks are still. You walk through a grove of whistling casuarinas, sown all at once, they say, when a storm spewed up the seeds from somewhere years ago, and come out at a whitewashed house set by itself in a clean-swept shady yard. Beside the house is a little restaurant, a roof with three tables and bottled drinks from Tampa and Blue Mountain coffee; and you go to a table as if it were what you came for. A Negro girl makes coffee for you and then sits down to talk, not troubled by your being white, talking as anybody would who lived in lonesome country.