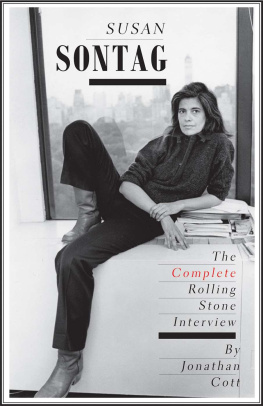

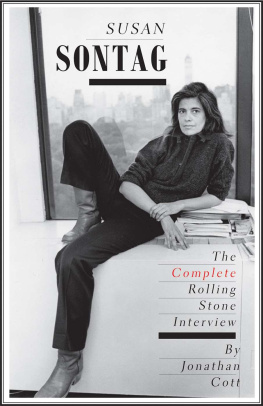

Susan Sontag

Susan Sontag

The Complete Rolling Stone Interview

JONATHAN COTT

Published with assistance from the foundation established in memory of

Philip Hamilton McMillan of the Class of 1894, Yale College.

Copyright 2013 by Jonathan Cott.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including

illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107

and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public

press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational,

business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail

sales.press@yale.edu (U.S. office) or sales@yaleup.co.uk (U.K. office).

Designed by Sonia Shannon.

Set in Electra type by Integrated Publishing Solutions.

Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Sontag, Susan, 19332004.

Susan Sontag : the complete Rolling Stone interview / Jonathan Cott.

pages cm

Includes index.

ISBN 978-0-300-18979-7 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Sontag, Susan, 1933

2004Interviews. 2. Authors, American20th century

Interviews. 3. Motion picture producers and directorsUnited States

Interviews. I. Cott, Jonathan. II. Title.

PS3569.O6547Z46 2013

818.54dc23

[B]

2013003894

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992

(Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

He becomes a disturber of the intellectual peace, but only at the cost of becoming an intellectual wayfaring man, a wanderer in the intellectual No Mans Land, seeking another place to rest, farther along the road, somewhere over the horizon. They are neither a complaisant nor a contented lot, these aliens of the uneasy feet.

THORSTEIN VEBLEN

When a person dies, we lose a library.

OLD KIKUYU SAYING

Contents

Preface

THE ONLY POSSIBLE metaphor one may conceive of for the life of the mind, wrote the political scientist Hannah Arendt, is the sensation of being alive. Without the breath of life, the human body is a corpse; without thinking, the human mind is dead. Susan Sontag agreed. In the second volume of her journals and notebooks (As Consciousness Is Harnessed to Flesh), she declared: Being intelligent isnt, for me, like doing something better. Its the only way I exist. I know Im afraid of passivity (and dependence). Using my mind, something makes me feel active (autonomous). Thats good.

Essayist, novelist, playwright, filmmaker, and political activist, Sontag, who was born in 1933 and died in 2004, was an exemplary witness to the fact that living a thinking life and thinking about the life one was living could be complementary and life-enhancing activities. Ever since the 1966 publication of Against Interpretationher first collection of essays that ranged joyously and unpatronizingly from the Supremes to Simone Weil, and from films like The Incredible Shrinking Man to MurielSontag never wavered in her loyalties to both popular and high culture. As she remarked in the preface to the thirtieth-anniversary republication of her book, If I had to choose between the Doors and Dostoyevsky, thenof courseId choose Dostoyevsky. But do I have to choose?

A proponent of an erotics of art, she shared with the French writer Roland Barthes not only what he called the pleasure of the text but also what she described as his vision of the life of the mind as a life of desire, of full intelligence and pleasure. In this regard, she was following in the footsteps of William Wordsworth, who, in his Preface to Lyrical Ballads, defined the poets role as that of giving immediate pleasure to a human Beingan undertaking that he took to be an acknowledgement of the beauty of the universe and an homage paid to the native and naked dignity of manand insisted that turning that principle into reality was a task light and easy to him who looks at the world in the spirit of love.

What makes me feel strong? Sontag asked herself in one of her journal entries, giving as her answer: Being in love and work, and affirming her fealty to the hot exaltations of the mind. Clearly, for Sontag, loving, desiring, and thinking were, at their root, essentially coterminous activities. In her fascinating book Eros the Bittersweet, the poet and classicist Anne Carsona writer whom Sontag greatly admiredproposed that there would seem to be some resemblance semblance between the way Eros acts in the mind of a lover and the way knowing acts in the mind of a thinker, and Carson added: When the mind reaches out to know, the space of desire opensa sentiment echoed by Sontag in her essay on Roland Barthes when she remarked that writing is an embrace, a being embraced; every idea is an idea reaching out.

In a 1987 symposium sponsored by PEN American Center that was devoted to the work of Henry James, Sontag expanded on Anne Carsons notion of the indissoluble connection between desiring and knowing. Rejecting the criticisms often made about Jamess arid and abstract vocabulary, Sontag countered: His vocabulary is in fact one of munificence, of plenitude, of desire, of jubilation, of ecstasy. In Jamess world, there is always moremore text, more consciousness, more space, more complexity in space, more food for consciousness to gnaw on. He installs a principle of desire in the novel, which seems to me new. It is epistemological desire, the desire to know, which is like carnal desire, and often mimics or doubles carnal desire. In her journals, Sontag describes the life of the mind with the following words: avidity, appetite, craving, longing, yearning, insatiability, rapture, inclination; and it is not difficult to imagine that Sontag might have felt that Anne Carson was in fact speaking for both of them when she confessed that falling in love and coming to know make me feel genuinely alive.

In all of her endeavors, Sontag attempted to challenge and upend stereotypical categories such as male/female and young/old that induced people to live constrained and risk-averse lives; and she continually examined and tested out her notion that supposed polarities such as thinking and feeling, form and content, ethics and aesthetics, and consciousness and sensuousness could in fact simply be looked at as aspects of each othermuch like the pile on the velvet that, upon reversing ones touch, provides two textures and two ways of feeling, two shades and two ways of perceiving.

In her 1965 essay On Style, for example, Sontag wrote: To call Leni Riefenstahls Triumph of the Will and Olympiad masterpieces is not to gloss over Nazi propaganda with aesthetic lenience. The Nazi propaganda is there. But something else is there too the complex movements of intelligence and grace and sensuousness. A decade later, in her essay Fascinating Fascism, she reversed the pile, commenting that Triumph of the Will was the most purely propagandistic film ever made, whose very conception negates the possibility of the filmmakers having an aesthetic or visual conception independent of propaganda. Where she once focused on the formal implications of content, Sontag would explain, she later wished to investigate the content implicit in certain ideas of form.

Describing herself as both a besotted aesthete and an obsessed moralist, Sontag might well have concurred with Wordsworths notion that we have no sympathy but what is propagated by pleasure and that wherever we sympathize with pain it will be found that the sympathy is produced and carried on by subtle combinations with pleasure. So it is not surprising that while Sontag fully embraced the pleasures of what she called a pluralistic, polymorphous culture, she never ceased from regarding the pain of othersthe title she gave to the last book she wrote before her deathnor from attempting to ameliorate it.

Next page