Susan Sontag

Titles in the series Critical Lives present the work of leading cultural figures of the modern period. Each book explores the life of the artist, writer, philosopher or architect in question and relates it to their major works.

In the same series

Georges Bataille Stuart Kendall Charles Baudelaire Rosemary Lloyd Simone de Beauvoir Ursula Tidd Samuel Beckett Andrew Gibson Walter Benjamin Esther Leslie John Berger Andy Merrifield Jorge Luis Borges Jason Wilson Constantin Brancusi Sanda Miller Bertolt Brecht Philip Glahn Charles Bukowski David StephenCalonne William S. Burroughs Phil Baker John Cage Rob Haskins Fidel Castro Nick Caistor Coco Chanel Linda Simon Noam Chomsky Wolfgang B. Sperlich Jean Cocteau James S. Williams Salvador Dal Mary Ann Caws Guy Debord AndyMerrifield Claude Debussy David J. Code Fyodr Dostoevsky Robert Bird Marcel Duchamp Caroline Cros Sergei Eisenstein Mike OMahony Michel Foucault DavidMacey Mahatma Gandhi Douglas Allen Jean Genet Stephen Barber Allen Ginsberg Steve Finbow Derek Jarman Michael Charlesworth Alfred Jarry Jill Fell James Joyce Andrew Gibson Carl Jung Paul Bishop Franz Kafka Sander L. Gilman Frida Kahlo Gannit Ankori Yves Klein Nuit Banai Lenin Lars T. Lih Stphane Mallarm RogerPearson Gabriel Garca Mrquez Stephen M. Hart Karl Marx Paul Thomas Eadweard Muybridge Marta Braun Vladimir Nabokov Barbara Wyllie Pablo Neruda Dominic Moran Octavio Paz Nick Caistor Pablo Picasso Mary Ann Caws Edgar Allan Poe Kevin J. Hayes Ezra Pound Alec Marsh Marcel Proust Adam Watt Jean-Paul Sartre Andrew Leak Erik Satie Mary E. Davis Arthur Schopenhauer Peter B. Lewis Susan Sontag Jerome Boyd Maunsell Gertrude Stein Lucy Daniel Richard Wagner Raymond Furness Simone Weil Palle Yourgrau Ludwig Wittgenstein Edward Kanterian Frank Lloyd Wright Robert McCarter

Susan Sontag

Jerome Boyd Maunsell

REAKTION BOOKS

for Tessa

Published by Reaktion Books Ltd

33 Great Sutton Street

London EC1V 0DX, UK

www.reaktionbooks.co.uk

First published 2014

Copyright Jerome Boyd Maunsell 2014

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers

Page references in the Photo Acknowledgements and

Index match the printed edition of this book.

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Bell & Bain, Glasgow

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

eISBN: 9781780233291

Contents

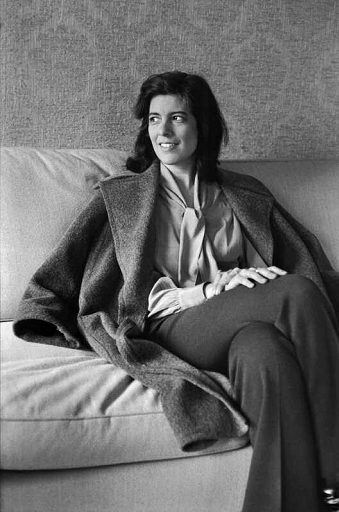

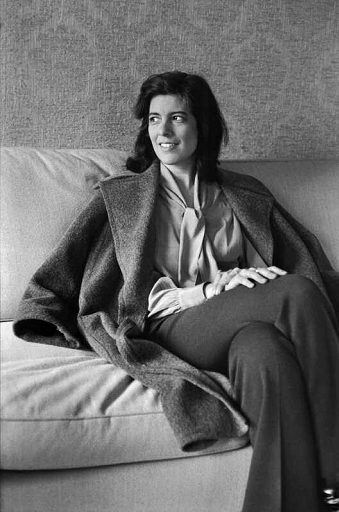

Susan Sontag by Henri Cartier-Bresson, 1972.

1

Beginnings, 19331950

In the end we all return to our beginnings.

Susan Sontag, American Spirits (1978)

Susan Sontag wrote essays, film scripts, novels, plays, short stories and her essays, in particular, display an extraordinary range of interests, in art, cinema, dance, drama, politics, photography and opera, as well as literature, always her first love but she never wrote an autobiography portraying her life in full. In the early 1970s, soon to turn 40, she thought very briefly about writing a book structured around several different themes in her life, although she never did so, perhaps because she felt it was too early. This project was likewise never attempted, joining the ranks of the books Sontag planned to write one day.

But Sontag did publish two fragmentary autobiographical pieces in her lifetime: the short memoir Pilgrimage and the short story Project for a Trip to China, which deal with aspects of her childhood, each painting it in a different light. Pilgrimage turns mainly on a visit Sontag paid as a teenager to the writer Thomas Mann at his home in Los Angeles in the late 1940s; Project for a Trip to China focuses on Sontags father and on her preparations to visit China, where she was probably conceived, for the first time. The tone in Pilgrimage, written in the mid-1980s and published in the New Yorker, is ironic, self-mocking, contemptuous, wondrous, embarrassed; while Project for a Trip to China, written in the 1970s, displays humour, pathos, nostalgia and melancholy. Both pieces reveal, in recounting different voyages away from herself, much about Sontags childhood and her attitude towards it.

Privately, Sontag also kept a diary from her early adolescence onwards, which by her death ran to around a hundred notebooks. The diaries record her life as it was lived, and as she wanted to live it, day by day, with an incredible, even exemplary, avidity for books, for experience, for love, for conversation, for knowledge, for art, for company almost a series of different, overlapping lives. As they went on, increasingly the diaries became creative workbooks as well, listing ideas for essays, stories and novels alongside accounts of Sontags life and loves. They also contain, intermittently but persistently, fragments of reflective autobiography on Sontags family and origins, including two lists of memories she wrote in 1957, turning 24, called Notes of a Childhood. Made up of disconnected phrases, impressions and sentences, recounted in the first list without chronological order and grouped into two sections in the second, these Notes are true to the workings of memory in their lack of sequence and give a raw portrait of Sontags youth.

The brevity of these texts on youth suggests an unwillingness to look back and reminisce for long, while the repeated attempts show her fascination. Sontag also often spoke about her youth in interviews. Her childhood, she said, was a prison sentence from which she escaped as soon as possible.own childhood, of being alien to her beginnings. As an adult Sontag tried to extricate herself from her own early biography, yet all her fragmentary attempts, other than the diaries, to write autobiography deal only with the very beginnings which she disavowed: a childhood of half-formed allegiances, arrivals and departures, enticingly glimpsed vistas that soon faded from view forever.

Susan Rosenblatt, later Sontag, was born in Manhattan on 16 January 1933, the first child of Jack Rosenblatt and Mildred Jacobson, who were both in their mid-to-late twenties and ran a fur trading business in China. Susans young parents had been raised in New York and came from Jewish families which had left Europe for America: Jacks parents, Samuel and Gussie, from Austria, and Mildreds parents, Isaac and Dora, from Russian-occupied Poland. She asked again and received the same answer; even in the 1970s she said that she did not know exactly where the Rosenblatts came from.

Susans parents were away in China for much of her early childhood. Mildred came back from China to Manhattan to deliver Susan, yet she returned there after the birth, leaving Susan with the extended family in New York. An Irish nanny, Rose McNulty, or Rosie, played a large role in bringing up Susan over the following years. Mildred revisited New York to have a second child, Judith, on 27 February 1936; Susan remembered visiting her in hospital with Rosie after the birth. This fragile and mysterious connection with China was soon severed abruptly. When Mildred finally came back to New York and her two children for good, it was as a widow, after Jack Rosenblatt died of pulmonary tuberculosis on 19 October 1938 in the German American Hospital in Tientsin, northern China. Susan was five years old.