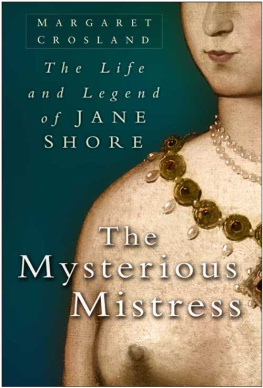

The

Mysterious

Mistress

The

Mysterious

Mistress

The Life and Legend

of J ANE S HORE

M ARGARET C ROSLAND

First published in 2006

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL 5 2 QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2011

All rights reserved

Margaret Crosland, 2006, 2011

The right of Margaret Crosland, to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 7091 7

MOBI ISBN 978 0 7524 7092 4

Original typesetting by The History Press

The past exudes legend:

There is no life that can be recaptured wholly, as it was.

Which is to say that all biography is ultimately fiction.

Bernard Malamud, Dubins Lives,

1979, p. 20

Read no history:

nothing but biography, for that is life without theory.

Benjamin Disraeli, Contarini Fleming,

1832, Part I, Ch. 23

Contents

Acknowledgements

I n writing about Jane Shore, the background to her life and her legend, I have received essential and valuable help from many individuals and organisations. Particularly important has been the groundbreaking research by Nicolas Barker and the late Sir Robert Birley concerning her family, their London life and Janes possible connection with Eton College, published in 1972 in Etoniana Nos. 125 and 126. New information also came from Desmond Seward in his 1995 study The Wars of the Roses and the Lives of Five Men and Women in the Fifteenth Century.

In addition Professor J.L. Harner of Texas A&M University gave me his unpublished dissertation Jane Shore: A Biography of a Theme in Renaissance Literature and indicated several hard-to-find sources of reference and information.

Other information has come from the Group Archives Unit at Barclays Bank plc, the British Film Institute, the Monumental Brass Society, the Richard III Society, the National Portrait Gallery and Tate Britain, London; many libraries have been helpful: the Bodleian Library, the British Library, the Guildhall Library, the Huntingdon Library in San Marino, California, the Pepys Library, Cambridge and the Poetry Library, London. The Dictionary of National Biography (2004) has also been constantly useful.

I am especially grateful to the Billingshurst branch of West Sussex County Libraries, where the staff have been unfailingly helpful in all ways.

I have also received helpful cooperation from Bill Alexander; Professor Sir John Baker (Cambridge); Nick Baker, Collections Administrator, Eton College; Catherine Ellis carried out wide-ranging Internet research. Madge Madden-Colenso and Mike Heritage took me to Hinxworth in Hertfordshire where Mrs Yvonne Tookey, Secretary to the Parochial Church Council, showed me the Lambert-Lynam family memorial brasses in the church of St Nicholas. Further help came from Geoffrey Wheeler, Anne Easton, Philip Heritage, Andrew Player, Elfreda Powell, Jan Stadler and my agent Jeffrey Simmons. My friend Bren Newman has supported and educated me constantly in the world of computer technology; I cannot thank her enough for her advice and cooperation.

Finally, I would especially like to thank Jaqueline Mitchell, my commissioning editor at Sutton Publishing, and the other members of the team: Anne Bennett, Jane Entrican and the unsung heroes and heroines in the back office.

M.C.

Introduction

One day I wrote her name upon the strand,

But came the waves and washd it away...

Edmund Spenser, Amoretti, 1595

J ane Shore was the mistress of King Edward IV of England for at least the last twelve years of his life, from 1471 or 1472 until his death in 1483, but if he lived all his life in the glare of publicity and had to fight for his throne twice over, she has remained in the shadows. There are at least two reasons for this: few women in the fifteenth century, apart from queens, certain aristocrats, and a few who were prominent within or near the Church, were able to enjoy any real independence; and the lives of others, if mentioned at all, with varying degrees of inaccuracy, were not usually recorded in detail. Jane Shore, unlike many royal mistresses, especially those in later centuries, did not seek fame or indeed rewards. As a result even her name, if considered worth including, has usually been relegated to footnotes or brief references in books about other people.

To revert to Edmund Spensers imagery, the waves of time may have washed her name away briefly, but the tide of reputation unexpectedly soon came in again and magically restored it. No magic was involved: her survival in legend was due to the poets and dramatists who wrote about her, passing on her story and interpreting her past behaviour in the light of changing social conditions. They needed a real-life heroine, an icon. No new media ever ignored her, a successful eighteenth-century play was translated into French and German, leading to operas with French and Italian libretti, four films were made about her in the early days of cinema, aspects of her story have led to PhD dissertations in American universities and analytical essays in Britain.

During her lifetime she was described and condemned as a harlot, a word originally used to describe men but later restricted to women. She was not a prostitute, not a courtesan, for she came from the middle class and did not try to find favour by cultivating anyone who happened to be near the court. Yet without much effort it was the king who sought her out she found herself occupying the top job, the best job available to women at the time: she became the kings mistress, and she was the mistress he really wanted. He had usually had many of them in a quick-moving procession. Safety in numbers, his wife Elizabeth Woodville may have thought, and King Edward never deserted this beautiful widow whom he had married in secret against everyones wishes. At the same time he annoyed her because he sacked all the other women but insisted on keeping Jane. Sir Thomas More, writing in the next century, explained why: but her he loved. Sadly, the king died in 1483 and Jane was on her own.

There are frustrating gaps in the records of Janes life but many of them can be filled from the evidence of her times, dominated from the start to the finish of her life by rebellion, war, violence, jealousy, sexual ambition, personal enmity, treason, murder, usurpation and ruthless social climbing.

Jane Shore was a name acquired in two stages by a young middle-class woman and in history and hearsay it has remained with her. Hers was not just a rags-to-riches story with secrets of some sort, but a story with undertones of family breakdown, romance and revenge which could only have happened during the later decades of the fifteenth century, when both royalty and middle-class society were changing fast, moving out of the Middle Ages towards the first decades of the Renaissance and the modern world. If Jane had not been so close to King Edward IV for twelve years or so her name would probably not have been known or remembered outside a few pages included in a much contested unfinished work by Sir Thomas More and a few cynical mentions in Shakespeares tragedy