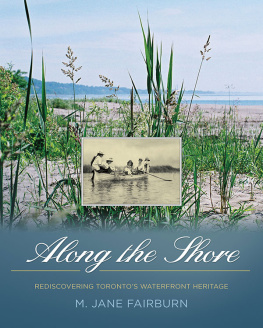

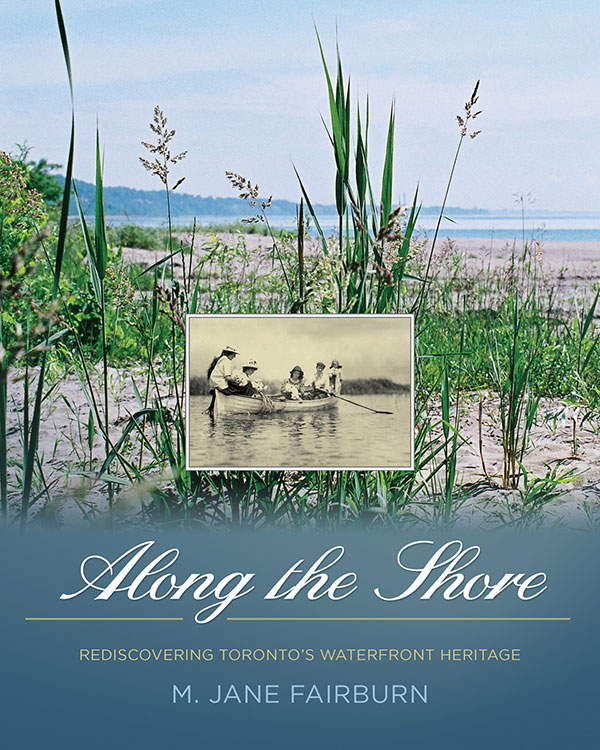

M. Jane Fairburn

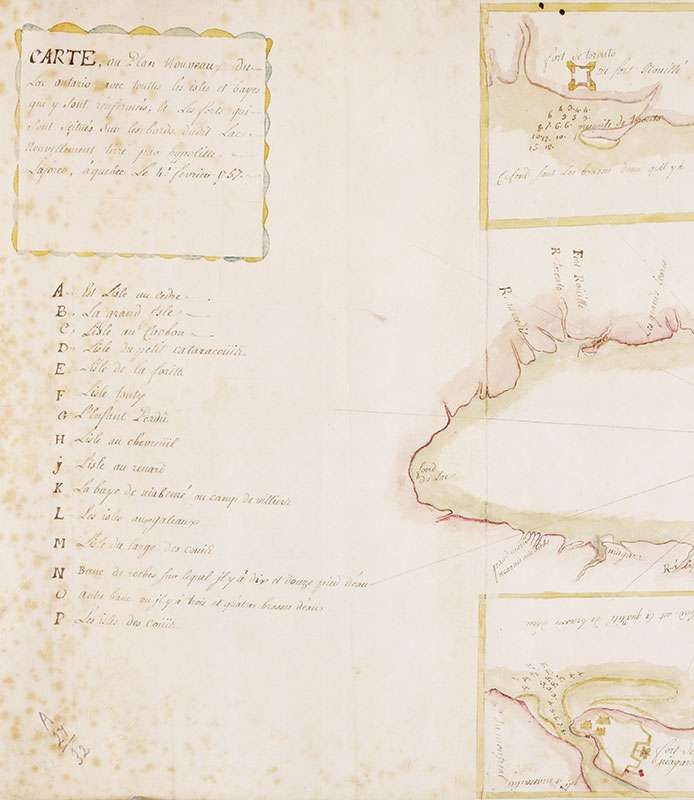

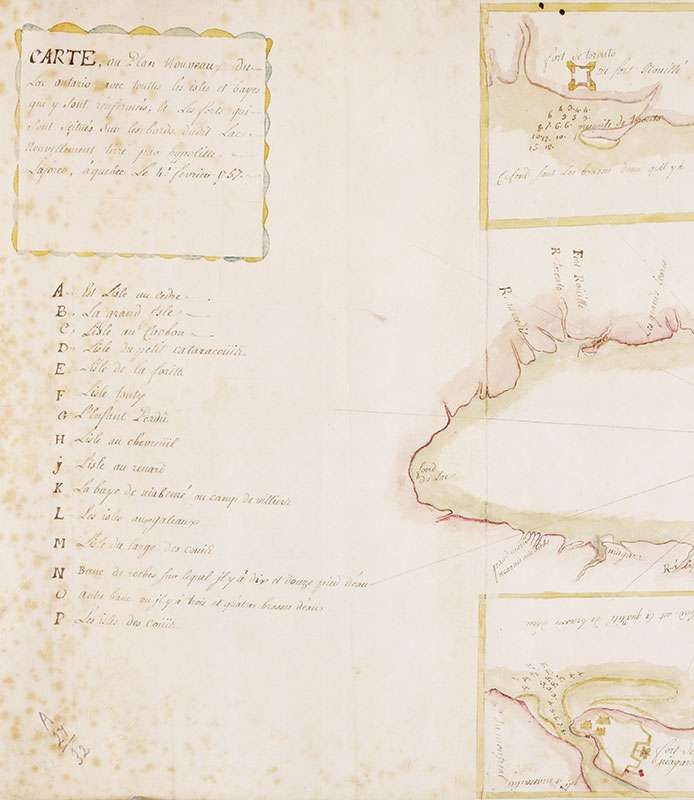

Carte au plan nouveau du lac Ontario, 1757. Ren-Hippolyte Laforce, British Library Board, Add.MS.57707.folio10

This land like a mirror turns you inward

And you become a forest in a furtive lake;

The dark pines of your mind reach downward,

You dream in the green of your time,

Your memory is a row of sinking pines.

Explorer, you tell yourself, this is not what you came for

Although it is good here, and green;

You had meant to move with a kind of largeness,

You had planned a heavy grace, an anguished dream.

But the dark pines of your mind dip deeper

And you are sinking, sinking, sleeper

In an elementary world;

There is something down there and you want it told.

Gwendolyn MacEwen,

Dark Pines Under Water, The Shadow-Maker

Introduction

CANADIAN CLASSICAL PIANIST Glenn Gould once said that Toronto was one of the few cities in the world in which he could live because it imposed no cityness upon him. This statement may seem somewhat curious, given that at the time of its utterance Toronto was a rapidly growing conurbation of over two million people, with suburbs that radiated out in all directions from a busy central core. Yet perhaps not. Perhaps Goulds view was, in part, influenced by where he was raised, Torontos Beach, where within a short five or ten minute stroll down a hill, or through a leafy ravine, he could reach the limit of the city and stand along the shore of one of North Americas massive inland seas, Lake Ontario.

Though Goulds favourite place in the Beach was the waters edge, he also roamed Toronto Bay, tracking the freighters from far-off exotic locales that cruised up the St. Lawrence from the Atlantic Ocean into Lake Ontario, finally arriving at Canadas great interior maritime city, Toronto. Lieutenant Governor John Graves Simcoe, who visited Toronto Bay in May of 1793, was also attracted to the site but for different reasons: the sandy peninsula in front of the mainland made for a natural sheltering harbour in the event of an anticipated American attack. Toronto also stood at the junction of two ancient aboriginal transportation corridors: the relatively flat Lakeshore Trail and the Toronto Carrying Place, whose two branches, near the mouths of the Rouge and Humber Rivers, served as access points to the Upper Great Lakes and the interior regions of Canada. Attracted by its strategic position, Lieutenant Governor Simcoe named the site York in 1793, though it was later re-named Toronto.

Glenn Gould out in Lake Ontario, the Beach, 1956 Jock Carroll, LAC, e011067053

The length of the shoreline of modern Toronto has greatly increased since its inception in 1793, and it now stretches from the Rouge River in the east to Etobicoke Creek in the west. Likewise, as the city has grown, the northern boundary of Toronto has moved farther and farther away from the waters edge, so much so that for many city residents today, the lake may seem somewhere on the periphery and not part of their active awareness. Everywhere and always, beyond the crumbling Gardiner Expressway and the rooflines of the Royal York Hotel, the peaks and crevices of the Scarborough Bluffs, the near shore waters of the Island, and the mouth of the Humber River, stretch the waters of Lake Ontario, within our reach yet perceived by many of us as being almost impossibly remote.

Yet in the early days of settlement, the lake was the source of Torontos existence. It provided a vital hub for industry, trade, transportation, and the movement of goods, which made pioneer settlements possible, many of which began at or near the shore. Early on in Torontos development, the lake was also a key destination for leisure, sport, and entertainment, with a series of pleasure grounds, hotels, and amusement parks established at or near the lakefront by the late nineteenth century.

Even the many people who enjoy the waterfront today may take the lake itself for granted, yet the sheer magnitude and breadth of Lake Ontario often astounds the newcomer. We often forget that Lake Ontario is part of a series of lakes that live up to their attribution as great. Unparalleled anywhere in the world, the Great Lakes contain more than eighty per cent of North Americas fresh water, or about one-fifth of the worlds supply. Only the polar ice caps contain more fresh water than these enormous basins. Lake Ontario though the smallest of the Great Lakes, with a surface water area of some 7,340 square miles, and more than 700 miles upriver from the Atlantic remains our gateway to the ocean and all that lies beyond.

I have now lived a significant portion of my life along Torontos eastern shore. My experience with the lake is personal and remains one of connection, and for many years I have had at least one toe in the water. Yet it took an unanticipated close encounter with the lake about fifteen years ago to cement this relationship and set me on a journey of discovery a journey that continues to this day.

While running high above the lake on a frigid midwinter afternoon, I slipped on black ice on the first step down to the Scarborough Bluffs, an extremely steep incline known locally as Killer Hill. Below the hill, the Scarborough Bluffs plunge to the water some 250 feet below. As I lay there stranded, my cries were blown away by the gusts of wind that swirled around me. With my right ankle hanging from my leg at an unnatural angle, I could do nothing but wait to be discovered. Far below me the ice fog swirled along the surface of the lake, weaving its intricate patterns over the grim grey water. Despite being on the outskirts of Canadas most densely populated city, it seemed as though I had tumbled into a wilderness that remained raw and uncivilized. It was a lake I had never known.

Scarborough Bluffs, 2012 Keith Ellis

To be sure, I was at last seen and eventually rescued, and then I was promptly delivered into the hands of a marvellous surgeon. But long after my body had fully recovered, the time I had spent on the slope stayed with me. Where had I been? What was that all about? I found quite early in my journey that the questions I was asking related, first and last, to the spirit, the innermost nature of a particular place.

That place is the waters edge, where the city rubs shoulders with the natural world. Along the Shore turns our gaze back to the lake and four distinct communities and districts that remain connected to the waterfront and hug its shores, from the Rouge River in the east to Etobicoke Creek in the west: the Scarborough shore, the Beach, the Island, and the Lakeshore (composed of the communities of Humber Bay, Mimico, New Toronto, and Long Branch). Moving from east to west, Ill examine the unique landscape and geography, history, and people that make up each of these special places. Though each retains a separate identity, collectively they are a place rich in memory and imagination.

Along the Shore does not cover what we today still think of as the downtown core, nor does it address the communities near the waters edge that at one time were more directly connected to the lake, particularly those communities to the west of downtown that lie east of the Humber River, Parkdale and Swansea, and Leslieville, which is situated east of the Don River. Although the core has its own fascinating history, some 160 years have passed since downtown Toronto could be thought of as simply a waterfront community. With the advent of the railway age in the mid 1850s came a rapid period of industrialization and commercialization that saw the downtown develop into a centre of finance, commerce, government, and public entertainment.