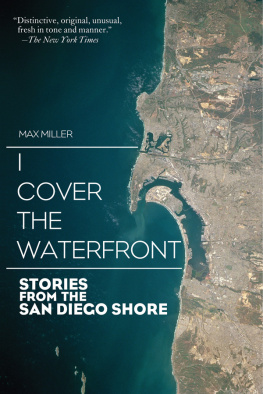

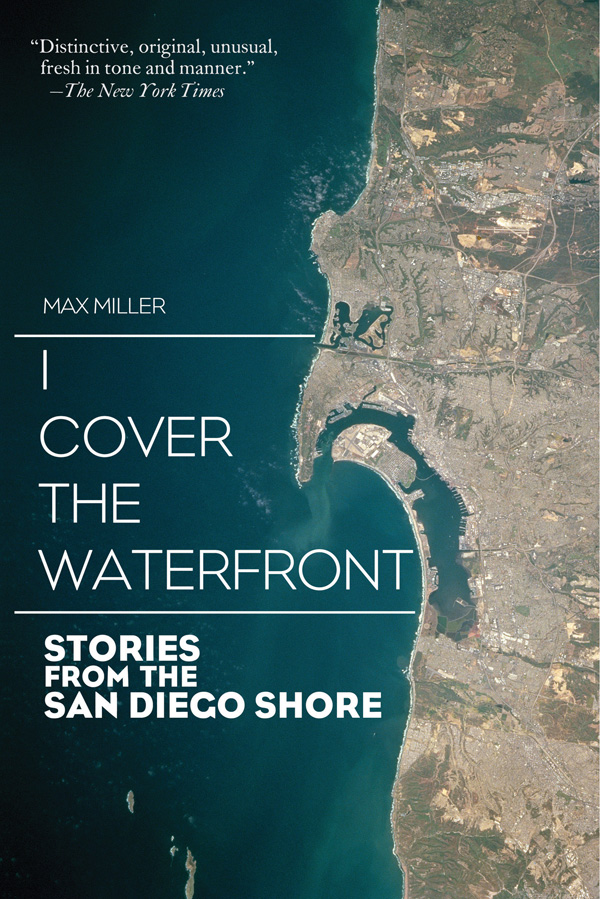

I COVER THE WATERFRONT

I COVER THE

WATERFRONT

STORIES FROM THE

SAN DIEGO SHORE

BY

MAX MILLER

First Skyhorse Publishing edition 2014

Copyright 1932 by E. P. Dutton & Co., Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

Cover design by Owen Corrigan

Print ISBN: 978-1-62914-454-2

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-63220-002-0

Printed in the United States of America

I COVER THE WATERFRONT

I

I HAVE been here so long that even the sea gulls must recognize me. They must pass the word along about me from generation to generation, from egg to egg.

Former friends of mine, members of my old university class, acquaintances my own age, have gone out to earn their six thousand a year. They have become managers, they have become editors, they have become artists. Yet here am I, what I was six years ago, a waterfront reporter.

True, I am called a good waterfront reporter in this city, as if the humiliation were not already great enough in itself. I shudder at the compliment, yet should feel fortunate in a way that so far I have escaped the word veteran. When I am called not only the best waterfront reporter but also the veteran waterfront reporter, then for sure all hope is dissolved. And I need look ahead then, only to that day when the company presents me with a fountain pen and a final check.

I am nearing twenty-eight, and should I by accident be invited to a home where literature is discussed, or styles, or Europe, the best I could do would be to crawl into the backyard. There I could sit tossing pebbles into the fountain until the hostess found me out. If she compelled me to come back into the house and join the conversation, my topics would have to be of sword-fishing, or of lobstering, or of hunting sardines in the dark of the moon, or of fleet gunnery practice, or of cotton shipments. The predicament has passed beyond my control. I am one of those creatures who remain permanent, who stay in one place, that successful men on returning home may see for the happiness of comparison. I am of the damned and the lost, and yet I do know more than I did six years ago when I first came here, a graduate in liberal arts.

I existed my first season on this waterfront buoyed by that common hope of mankind that by next year I would write a book, a novel composed of the characters I met. Quite tidily, too, I would insert my own silent sufferings, such as eating at the lunch counter downstairs where the sugar bowl is always chucked with brown lumps. These fishermen will dip coffee spoons back into it for the third or fourth helping. But instead of writing of this, I learned instead to take the lazy mans course and drink my coffee without sugar.

The second year blended into the third. The characters I had picked out for my novel gradually became more blurred to my complete understanding. Nobody was definitely good, nobody was definitely bad. The more I knew of them the less positive I became of which stand to take, and for a novel a writer does need a villain; a writer needs several of them. Even Evangeline, the brown-haired waitress, proved a disappointment to my plans. I had selected her to be the waterfront harlot. I had a drab death already prescribed for her, a death in which she would fling herself from the tugboat pier with only the silver moon as witness. The gentle bosom of the bay would cleanse her of her sorrow, would baptise her anew, and she would be carried by the tide to sea with a look of peace upon her world-wronged face. But unfortunately Evangeline does not need cleansing. In fact she has a home and a husband, rather a nice chap. He is a quartermaster on a destroyer based here. And even now I can hardly forgive Evangeline for this trick on me.

Of course if a writer were really desperate for harlots there are plenty of them around here. They follow the fleet from port to port as regularly as the wake of the vessels, but a person has to be an expert to distinguish them. I see the girls come down to the float where the shoreboats land, but often enough they turn out to be dutiful wives or high-school daughters. And the sailors, especially, are wise enough to keep their mouths shut until they know for sure.

At any rate the original characters I selected for my book never did show up. I have yet to see them. I do not know what has happened to them, but I have waited six years. I can wait no longer; I am getting too old, so must go ahead with what I already have on hand.

My studio, by the way, is upstairs in the tugboat office. The room is not mine. It belongs to the publicity agent of the deep-sea fishing barge. Until this book he has been a critic of all I write. When my news stories concerned his fishing barge he clipped them out. He keeps a scrapbook to show his employer at the end of the season. Some of my writings are being saved. I under-estimated myself.

The walls of this room are decorated with pictures of bluefin, yellowfin, skipjack, barracuda and mackerel. These are my inspiration. They are the left-over pictures he could not peddle to the papers. Men are holding the fish. The pictures where women are holding the fish are peddled. They were printed. He has none of them left but he keeps the others here.

The shingles of the roof show through the ceiling. The roof slopes so low on the south side that a person cannot stand up there. The room is quite small, and in summer stuffy with a sort of cobweb stuffiness.

Frequently the tugboat operators come up to see the publicity agent, my lone encouragement. They have questions to be answered, yet mostly they desire to read his library. The book in it is Rabelais, illustrated. He keeps it locked in the middle drawer to the right. The operators must not take the book downstairs to the pier, but must read it in the room, and first must see that their hands are wiped of grease. He keeps an eye secretly on them as they read; he is deathly afraid that one of them with a pencil might some day add insulting shadows to the naked ladies. And all this, then, is the ultimate of my literary environment. I who would have consented six years ago to have done book reviews while waiting for the job of theatre critic.

Next page