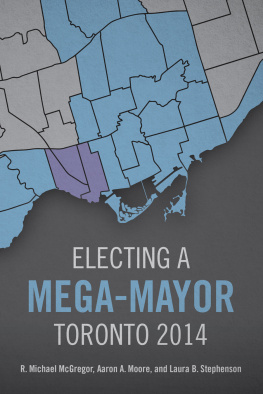

Undressed Toronto

From the Swimming Hole to Sunnyside, How a City Learned to Love the Beach, 18501935

Undressed Toronto: From the Swimming Hole to Sunnyside, How a City Learned to Love the Beach, 18501935

Dale Barbour 2021

25 24 23 22 21 1 2 3 4 5

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database and retrieval system in Canada, without the prior written permission of the publisher, or, in the case of photocopying or any other reprographic copying, a licence from Access Copyright, www.accesscopyright.ca, 1-800-893-5777.

University of Manitoba Press

Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada

Treaty 1 Territory

uofmpress.ca

Cataloguing data available from Library and Archives Canada

ISBN 978-0-88755-947-1 (PAPER)

ISBN 978-0-88755-951-8 (PDF)

ISBN 978-0-88755-949-5 (EPUB)

ISBN 978-0-88755-953-2 (BOUND)

Cover image: Bathers, Sunnyside, City of Toronto Archives, William James family Fonds 1244, Item 225, 1911.

Cover design by David Drummond

Interior design by Jess Koroscil

Printed in Canada

This book has been published with the help of a grant from the Federation for the Humanities and Social Sciences, through the Awards to Scholarly Publications Program, using funds provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

The University of Manitoba Press acknowledges the financial support for its publication program provided by the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund, the Canada Council for the Arts, the Manitoba Department of Sport, Culture, and Heritage, the Manitoba Arts Council, and the Manitoba Book Publishing Tax Credit.

Contents

Acknowledgments

Introduction

1 Central Waterfront: Testing the Waters

2 Central Waterfront: Vernacular Spaces

3 Toronto Island: Implementing a Beach

4 The Don River and the Bathing Boy

5 Humber River Encounters

6 Sunnyside and the Beach

Conclusion

Epilogue

Notes

Bibliography

Illustration Credits

Index

Acknowledgments

I need to thank Albert, Dupree, Joy, George, and countless others who left traces of their encounters with Torontos rivers and waterfront. Their moments of joy and tragedy brought Toronto to life for me in a way I never imagined possible. And I need to thank the Don River, a space of refuge while I was writing this book. I never knew I could love a river until I met the Don.

My research was conducted at the University of Toronto with the help of the Ontario Graduate Scholarship Program, including the Arthur Child, Rene Efrain Memorial, and Thomas and Beverley Simpson scholarships, and the Jeanne Armour Scholarship. St. Johns Colleges Visiting Researcher in Western Canadian Studies Fellowship and the University of Winnipegs Sanford Riley Postdoctoral Fellowship have supported me during the publication process. An earlier version of Chapter 4: The Don River and the Bathing Boy appeared in Urban History Review in 2019 and I appreciate their permission to use the material here.

I owe a debt of gratitude to Steve Penfold, Ian Radforth, Mariana Valverde, Sean Kheraj, Ruth Sandwell, and Sean Mills for guiding my research.

Thank you to John Huzil, Lawrence Lee, and Sharon Anderson at the City of Toronto Archives, PortsToronto archivist Jeff Hubbell, and to the Toronto Public Library system, Archives of Ontario, and Library and Archives Canada.

Friends, colleagues, and inspirations: Ben Bradley, Bret Edwards, Peter Mersereau, Ryan Masters, Jonathan McQuarrie, Jennifer Evans, Lindsay Sidders, Vanessa McCarthy, Steven McClellan, Julia Rady-Shaw, Beth Jewett, Sharon Wall, Adele Perry, Veronique Church-Duplessis, Casper, Rembrandt, and Roxie. Brandon University kept my head above water while I was completing my manuscript: it was a pleasure to wander by and visit David Winter, James Naylor, Patricia Harms, Rhonda L. Hinther, and Lynn MacKay.

At the University of Manitoba Press, David Carr has always had my back. Thank you to the entire team.

And, of course, my mom and dad, Flo and John Barbour. You taught me how to read, Mom. I couldnt have done this without you.

Undressed Toronto

Introduction

As the end of summer neared in 1925, a Globe writer mused about the relationship between Torontos boys and the citys natural environment in an editorial entitled A Summer Idyll Urbanized:

Ifone visits certain secluded sections of the Don or Humber, set aside by the city fathers for the benefit of the citys youngest sons, and well protected against feminine intrusion, one realizes that boys seek water as inevitably as water seeks its own level. There is a natural affinity between a boy and a swimmin hole, just as marked as the natural antipathy between a boy and a washbowl.... These happy little urchins skipping about in frolic zestfulness, or basking in peaceful indolence upon the sand, all clad in nothing but coats of tan that vary in shade from the mere pink of newcomers to the deep walnuts stain or caf-au-lait of habitus, make it seem that the Age of Innocence has come again.

Such spaces were reservoirs of civic health that could protect and rejuvenate the city and they needed to be maintained and expanded, the Globe writer argued, because there is no wiser or cheaper investment for future citizenship than merely utilizing natural advantages in order to prevent the diseases or deformities due to overcrowded and undernourished tenement district life. The seasonal rite of boys frisking about in all the charming freedom of native innocence, their lithe little forms radiating health and joy and the unstudied grace of vigorous statues flushed with eager young life spoke to the rejuvenation of society itself. But as it faced the growing threat of pollution the swimming hole was a precarious space in 1925. The Globe argued it would be an exceedingly regrettable invasion of the pastoral by the urban [if] any of the more private swimming places, where bathing suits are unnecessary, should have to be closed on account of preventable defects in sanitation.

The swimmin hole is a lucrative space for examining how Torontonians used the bathing boy as an icon to soften the transition into modernity. Within these Gardens of Eden bathers played without sin or shame. They created a community with its own rules, hierarchy, and even shared systems of knowledge: it was expected that those with a deeper tan would school the untanned newcomers in the ways of the swimming hole. The price of admission was stripping down and becoming one of the boys. Yet for all the swimming holes seeming seclusion, the bathers were often in plain view, portrayed as statues that captured the energy of youth. Toronto was caught between staring at its youthful urchins and averting its eyes to ensure their purity.

While the Globe mused that similar spaces should be set aside for girls to bathe, it was careful to add that they should be under the watchful eye of police matrons. Girls were an afterthought. The goal of the swimming hole was the production of vigorous masculinity. And like Peter Pan in Neverland, the sanctity of the swimming hole depended on the boys never growing up but instead remaining chaste figures within an all-male homosocial space.