I Remember Sunnyside

The Rise & Fall of a Magical Era

Revised Edition

by Mike Filey

Copyright Mike Filey, 1996

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise (except brief passages for the purposes of review), without the prior permission of Dundurn Press Limited. Permission to photocopy should be requested from the Canadian Reprography Collective.

We would like to express our gratitude to the Canada Council, the Ontario Arts Council, and the Book Publishing Industry Development Program of the Department of Communication for their generous assistance and ongoing support.

Care has been taken to trace the ownership of copyright material used in the text (including the illustrations). The author and publisher welcome any information enabling them to rectify any reference or credit in subsequent editions.

J. Kirk Howard, Publisher

Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data

Filey, Mike, 1941

I remember Sunnyside

Revised Edition

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 1-55002-274-1

1. Sunnyside Amusement Park (Toronto, Ont.)

History. I. Title.

GV433.C33T67 | 790.068713541 | C96-932162-7 |

Cover illustration: Herb Franklin

Editor: Nadine Stoikoff

Designer: Ron & Ron Design and Photography

Printer: Webcom

Printed and bound in Canada.

Second Printing, April 1998

Dundurn Press

8 Market Street, Suite 200

Toronto, Ontario

M5E 1M6

Dundurn Press

73 Lime Walk

Headington, Oxford

England 0X3 7AD

Dundurn Press

250 Sonwil Drive

Buffalo, New York

U.S.A. 14225

Dedication

To my grandmother, Martha Hatch, who first took me to the playground by the lake, and to my mother and father who kept taking me back.

This revised edition is also dedicated to the memory of those who assisted with the original work and have since passed away.

Contents

by Robert Thomas Allen

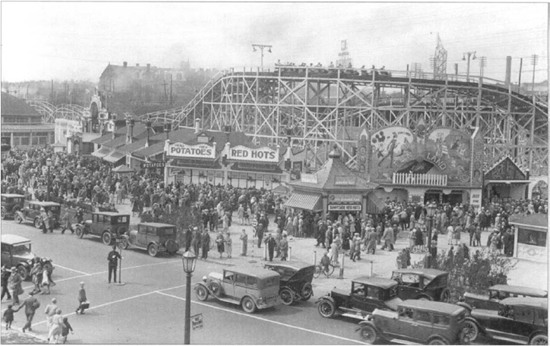

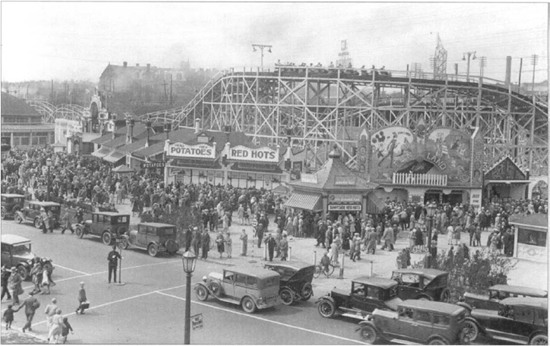

A train of ecstatic passengers on the Sunnyside Flyer roller-coaster roars by overhead as traffic pauses at the Lakeshore pedestrian crossover. The young fellow with the briefcase was on his way to earn a few dollars painting the owners initials in gold paint on the doors of their flivvers. The former Sunnyside Orphanage, recently converted into the new St. Josephs Hospital (and now St. Josephs Health Centre) can be seen on the hill in the background to the left.

This same view, as depicted by talented Burlington, Ontario, artist Herb Franklin, appears on the cover. Herb, who spent his early years in the Ossington/Dupont part of Toronto, records his memories of Sunnyside in his self-published book Street Stories of Toronto. Information on purchasing the book can be obtained by writing Herb, c/o 626 Fothergill Boulevard, Burlington, Ontario L7L 6E3.

Foreword

Robert Thomas Allen

One bright, still, hazy day I walked down past some beautiful willows at Sunnyside to a peaceful spot on the shore behind the bathing pavilion and sat at a battered old picnic table eating a hot dog and watching three kids skipping stones. In the distance I could hear the moan, hiss, growl, and whine of fourteen lanes of fast traffic. The fresh smell of the lake and of warm paint made me drowsy and I began to doze and my thought drifted back to the days of the old amusement park that used to be here and I imagined what I heard wasnt traffic, but the rumble and roar of the rides the whip, the Derby racer, the roller-coaster and the ecstatic screams of the girls (they must be all around seventy now).

Youd take a streetcar and get off at the station restaurant, where the Lakeshore streetcars headed southwest across a bridge over the railway tracks, and youd go down a long set of stairs into the smell of gun smoke, perfume, french fries, popcorn, and sparks from the Dodgem, and submerge into a crowd of fellow humans, as relaxing as sinking into a warm tub, and shuffle along past the weight-guesser, the rabbit run, the poker game, and fish pond the hoarse cries of front men exclaiming over the amazing skill of their customers and how close they were coming to winning prizes. The merry-go-round was a shadowy, breezy cave of polished brass and mirrors and carved wood where you could ride around on a charger, or a camel, holding onto a brass pole or sit in the Roman chariot one arm over the back like a debauched emperor, lulled by music and the faint breeze, with your worries flung gently outward by centrifugal force, sometimes falling in love with some girl who was waiting her turn, who floated past you rhythmically like someone in a lovely sance. There were two merry-go-rounds at Sunnyside: the Derby racer, now at the Canadian National Exhibition, and the Menagerie merry-go-round, which is now in Disneyland, California. Another magnificent Toronto merry-go-round that used to be at Toronto Island is now in Walt Disney World in Florida.

We didnt know it then, but we were in something more than a crowd at Sunnyside; we were in the mainstream of major sociological change. Sunnyside came in with the automobile not with the early models of the 1890s, but with the beginning of the automotive age when cars were to change our cities and our lives. The automobile was a magic carpet that smelled of rubber curtains and gasoline, the new smell of the future, progress, and adventure, and it invoked thoughts of remote country roads and shimmering lakes and far-off wonderful places of an exciting world.

We were still very aware of the marvel of being able to, say, drive down the Danforth or Bloor Street for a brick of ice cream and be back in some fabulous time, like eight minutes; and of the miraculous fact that you could get into your Ford coup outside your house, and sit comfortably behind a steering wheel until you reached Sunnyside, stop at the curb, pull on the emergency brake, and step out fifteen, twenty feet from, say, the shooting gallery. But Sunnyside created some of the first great traffic jams. There was one cop, with a hand-operated wooden stop-and-go sign shaped something like a living-room floor lamp. It was the first time somebody told you when you could move, and you got the feeling as you sat there looking at the line of cars, moving bumper to bumper about three feet at a time, with people eating ice cream cones stepping between the bumpers, that the whole world had gone mad. Men used to teach their wives to drive in those days and they would make them drive through Sunnyside on a busy warm evening, figuring that by the time they got from the Humber River to the Palais Royale theyd never forget how to change gears again, and I know women approaching their gold wedding anniversary who have never forgiven their husbands for this, and probably never will.

Sunnyside went through the Great Depression and into the beginning of the age of affluence. Over half that time, money was regarded as a precise gauge of value and a commodity hard to come by. It had absolute value. If someone had said when you spent, for instance, thirty cents on a ring-toss game without winning anything, that it was only a little bit of money, it would have been like saying it was only a little bit of your arm. You were prepared to lose it, but not to think of it as nothing. Your pay came folded in a flat brown envelope the size of a playing card, which during the Depression sometimes had a white slip in it saying that you were fired. You