IMAGES

of America

HISTORIC

CEMETERIES OF

LONG BEACH

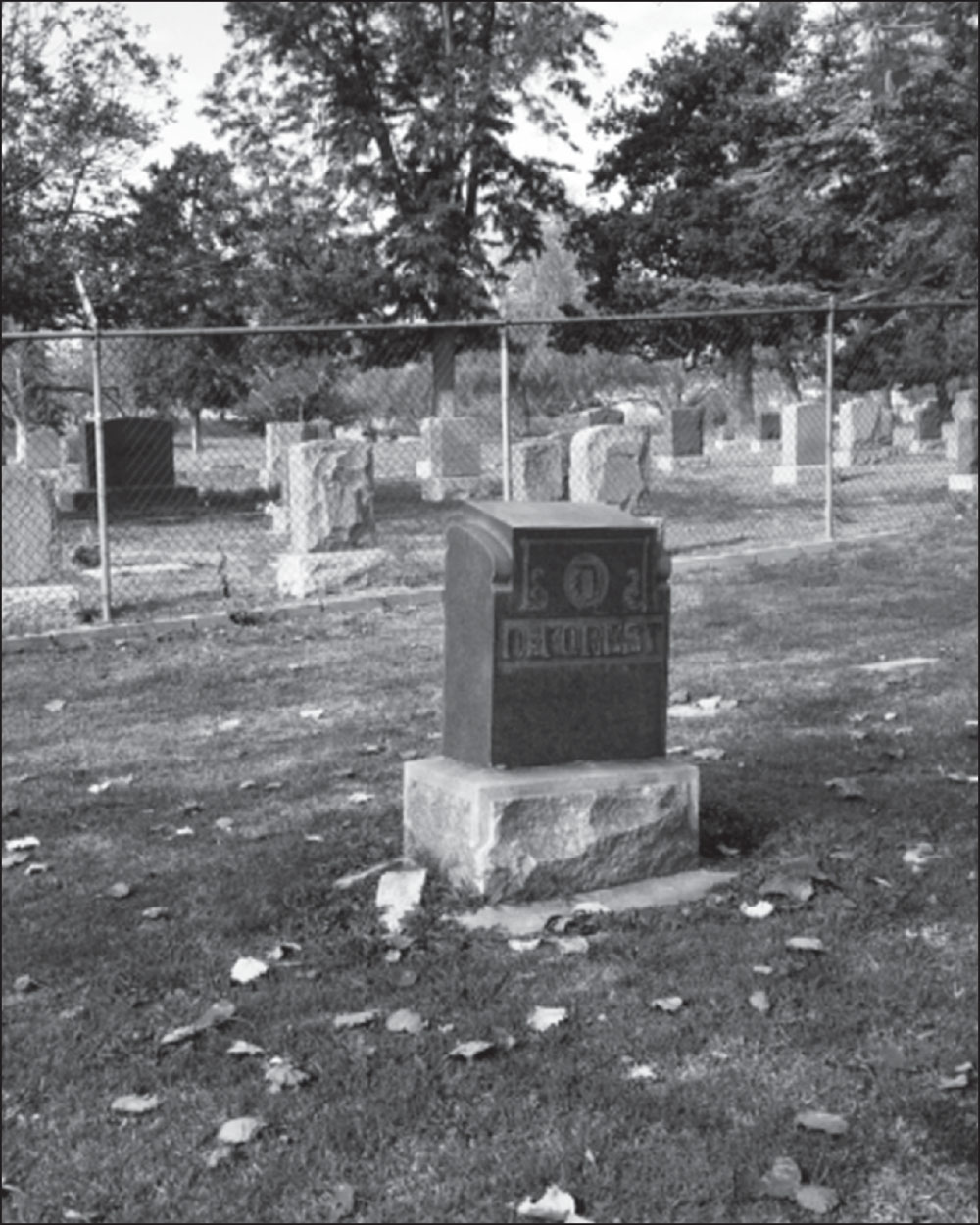

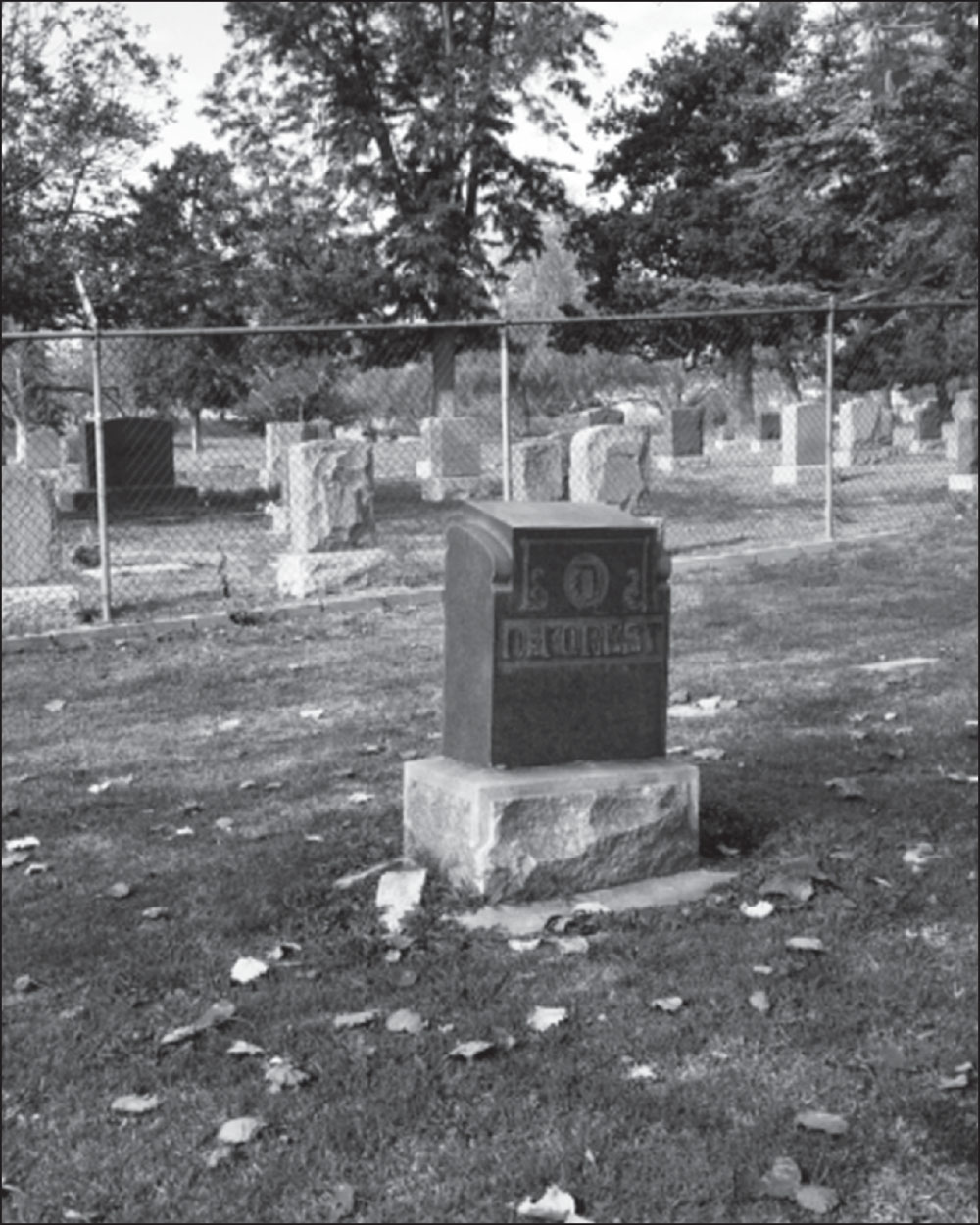

A chain-link fence separates the Municipal and Sunnyside Cemeteriesthe two oldest non-native burial grounds in Long Beach, California. Both are located on Willow Street on the sloping land of oil-rich Signal Hill. The Second Sunnyside Cemetery is several miles to the north and today is known as Forest Lawn Long Beach.

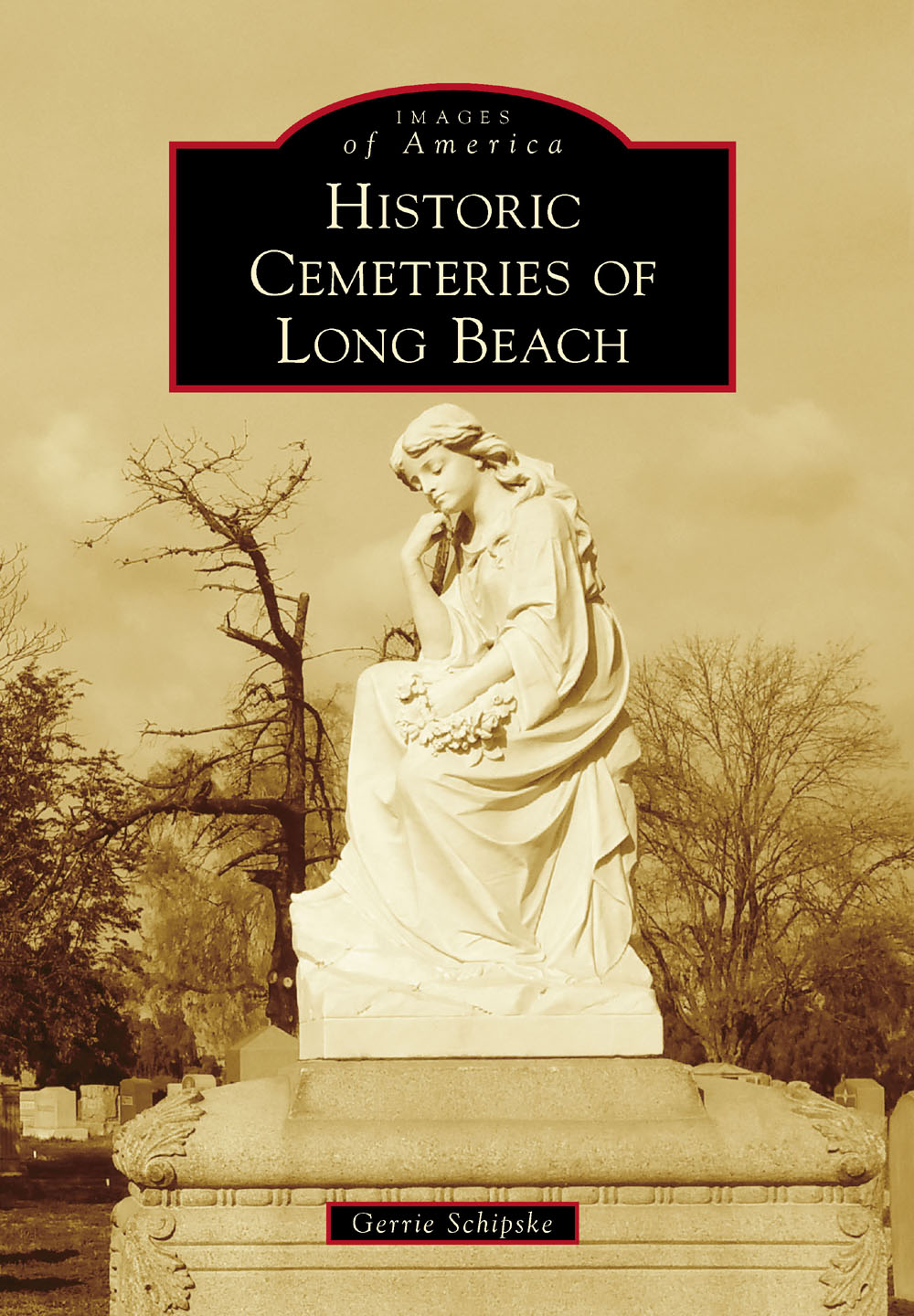

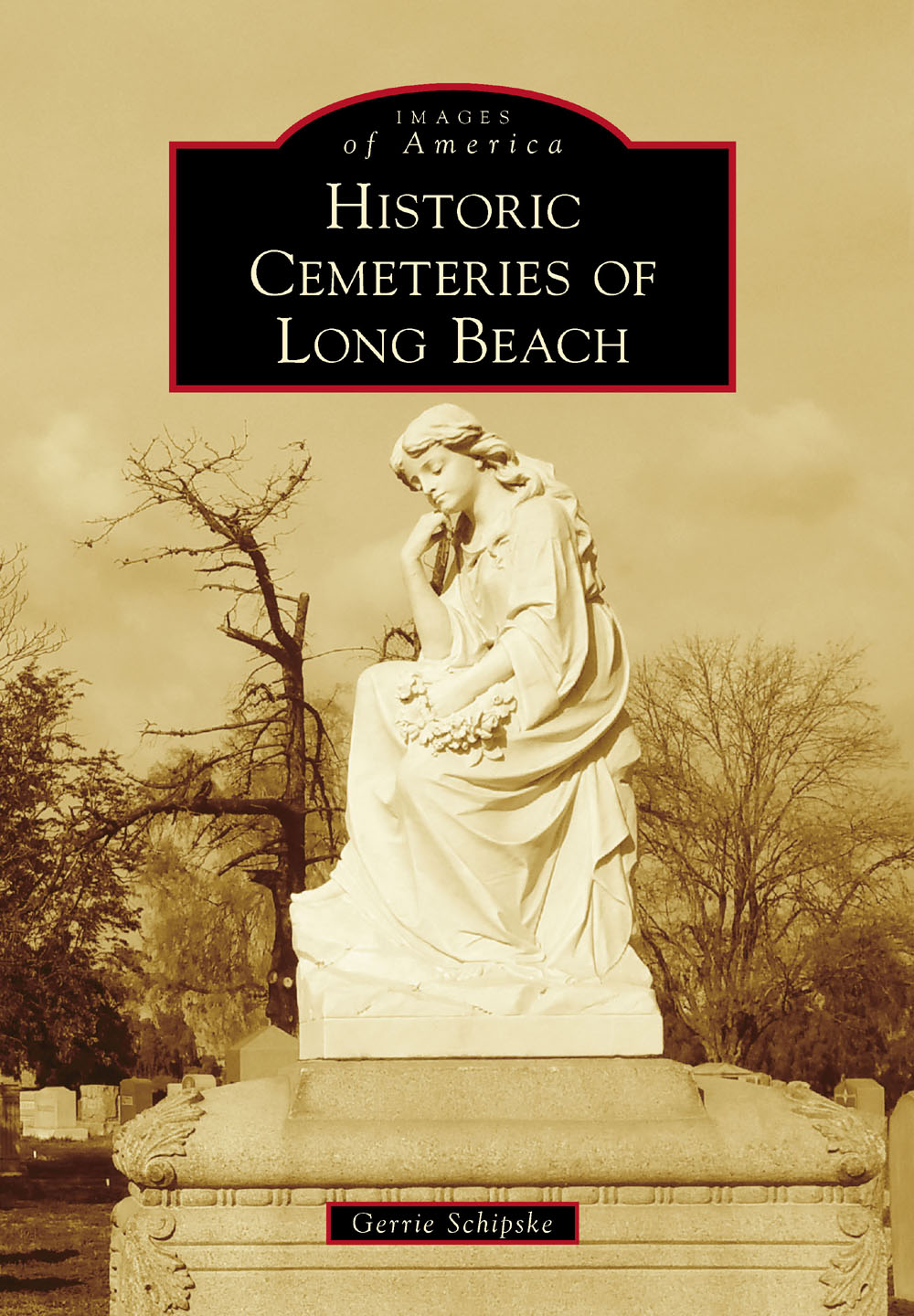

ON THE COVER: Ansel Adams made the Angel of Sorrows famous in 1939 when he took pictures of the statue against a background of hundreds of oil derricks. The authors photograph shows that most of the oil derricks are gone, but the statue remains atop the 1907 grave of Dr. Albert Rhea in Sunnyside Cemetery.

IMAGES

of America

HISTORIC

CEMETERIES OF

LONG BEACH

Gerrie Schipske

Copyright 2016 by Gerrie Schipske

ISBN 978-1-4671-1713-5

Ebook ISBN 9781439657652

Published by Arcadia Publishing

Charleston, South Carolina

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016941976

For all general information, please contact Arcadia Publishing:

Telephone 843-853-2070

Fax 843-853-0044

E-mail

For customer service and orders:

Toll-Free 1-888-313-2665

Visit us on the Internet at www.arcadiapublishing.com

To Flo Pickett, my partner in life, who listened so patiently as I told these cemetery stories over and over again. Thank you.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

A sincere thank-you to Michael Miner, a board member of Friends of Sunnyside Cemetery, who made records and access so readily available. The preservation of Sunnyside Cemetery is a labor of love for him, not only because he has family buried there, but because he understands that it is one of the remaining sites that provides a glimpse of early Long Beach history. Thank you also to Long Beach city manager Patrick West and Dustin Borrelli of the Public Works Department for providing access to city records. Unless otherwise noted, all images are from the authors collection. The following sources were also used: LOC (Library of Congress), LBPL (Long Beach Public Library), LAPL (Los Angeles Public Library), and the University of Southern California Digital Collections.

INTRODUCTION

Long Beach may contain some of the earliest burial grounds in California. Home of the Tongva natives, the eastern portion of Long Beach contains a dozen or more archeological sites that are believed to be ceremonial and burial sites.

The non-native cemeteries of Long Beach came in the late 1870s and early 1900s and are the final resting places of those born here and the many more who came in search of a better, healthier, and calmer life. They were doctors, bankers, real estate developers, teachers, politicians, lawyers, farmers, writers, evangelists, activists, entertainers, and veterans. They were their spouses, siblings, and children.

Some died within their first few minutes or years of life. Some were taken by disease, murder, accident, or suicide. Some have no marker to provide clues to their name and history. Most lived the long lives they hoped they would after leaving other states and coming to Long Beach.

One chronicler of cemeteries remarked in a 1921 edition of Park and Cemetery that Long Beach was a two grave town due to more than one half of the population being elderly retired couples who moved to Long Beach to live the remainder of their lives. With children living elsewhere, they only needed a two-grave lot.

Many early residents, some of whose names are immortalized as streets, parks, schools, and historic areas of the city, lie in one of the four cemeteries: William E. Willmore, whose American Colony eventually became the city of Long Beach; Col. Charles Heartwell, one of the first city water commissioners whose vision for use of water property led to the development of one of Long Beachs largest parks; F.W. Stearns, a prominent real estate developer whose father, T.P., served in the Civil War; and Dr. William Lawrence Woodruff, who promoted good health through his Woodruff Sanitarium. There are also a number of other prominent families, including those of Buffum, Bixby, Walker, Bush, Teel, and Shaw.

The history of these cemeteries parallels the changes in public attitude toward death and burial. Early cemeteries were removed from churchyards and placed in rural areas and made park-like. Funerals were no longer conducted in family parlors, but by those who would undertake the tasks in their own funeral parlors. Coffins became caskets to emphasize that the dead were only sleeping. Headstones, once stark and small, became ornate and large to indicate wealth.

There were no crematoriums or community mausoleums in Long Beach until 1922, when the second Sunnyside was opened. Before then, families wishing cremation or entombment went to other cemeteries.

Two of the Long Beach cemeteries are located on Signal Hill. These were originally farm lots in the American Colony and were thought to be largely unusable land because of the slope. In its earliest days, the Municipal Cemetery was known as Signal Hill Cemetery. It is not known for certain who is buried in the Municipal Cemetery because burial records were not required to be kept before 1905, and a fire destroyed much of the records in 1936. A headstone marking the 1878 death of 17-year-old Milton Neece appears to be the oldest in the cemetery.

The records for Sunnyside Cemetery are much more complete. The first plot purchased in 1907 was for Dr. A. Rhea, a retired Civil War physician who was deaf and was hit by a trolley while bicycling.

Both Sunnyside and the Municipal Cemeteries contain hundreds of Union and Confederate veterans of the Civil War, including Abraham Cleag, a former slave who served as a private in Company A of the 1st Colored Heavy Artillery Regiment in Knoxville and later as a janitor in Long Beach City Hall. Nelson Ward, a Union Medal of Honor recipient, is buried in Sunnyside Cemetery, as is Confederate Alexander Lawson, who served as the citys third prosecutor. Long Beach Post 181 of the Great Army of the Republic, an organization of Union Civil War veterans, was one of the largest. Only Sunnyside has a dedicated Civil War section on its Westside.

The 1921 discovery in Signal Hill of one of the largest oil fields in the world sparked an intense and long battle for oil drilling rights in and adjacent to the two cemeteries as thousands of oil derricks surrounded them. A second Sunnyside Cemetery was opened in 1922 several miles to the north with advertisements offering to remove and rebury those in the older Sunnyside Cemetery.

Famed photographer Ansel Adams was so intrigued by the surrealism of a cemetery surrounded by oil derricks that, in 1939, he photographed the white marble Angel of Sorrows that sits atop the grave of Dr. A. Rhea in Sunnyside Cemetery with the derricks in the background. The photograph appeared in Life magazine.

The new, ornate Sunnyside Mausoleum and Memorial Park attracted many families who liked the idea of an elegant funeral that cost little more than burial in the deteriorating Municipal Cemetery and older Sunnyside cemeteries.

In 1960, Forest Lawn purchased Sunnyside Mausoleum and Memorial Park and made extensive restorations and improvements. In 1974, an area was designated Rose of Sharon Memorial Gardens for the burial of those of the Jewish faith. Today, Sunnyside Mausoleum and Memorial Park are known as Forest Lawn Long Beach.

Next page