Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2015 by William G. Krejci

All rights reserved

First published 2015

e-book edition 2015

ISBN 978.1.62585.555.8

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015949906

print edition ISBN 978.1.46711.772.2

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Special thanks to the following for their priceless contributions and assistance: Jack Nickels, the Rocky River Historical Society; Louise Varisco, the Strongsville Historical Village; George and Mary Krejci, Chad Thomas, John Nanovsky, Matthew Rump, Ryan McCarbery, Patricia Mahon, Rebecca E. Haaga, Amanda Francazio and Greg Palumbo, the Lakewood Historical Society; Paul Nelson, the Western Reserve Fire Museum and Education Center; Gayle Hill and Charles Cassady Jr., the Western Reserve Historical Society; Ware Petznick, the Shaker Historical Society; Marcia Anselmo, the Gates Mills Historical Society; Roy Larick and Dave Lawrence, the Euclid Historical Museum; the Cleveland Public Library; Cleveland State University; Janet Wood; Lucy Fiore; and Laura Hine.

INTRODUCTION

As we go about our daily lives, we seldom, if ever, wonder what once occupied the places our feet take us. We constantly see things changing before our very eyes. A derelict building might get demolished to make way for a new shopping center. An old farm might be bulldozed and, in a few years, replaced by a modern housing development. A rare sight, however, is the removal of a cemetery. Yet it used to be a common occurrence.

Anyone who has seen the 1982 classic horror film Poltergeist knows that its a bad idea to relocate a cemetery and build on its former site, especially when you leave the bodies behind. First, your chairs begin to move on their own and then a tree almost eats your son. The next thing you know, your five-year-old daughter gets sucked into another dimension through a portal in her bedroom closet. Who needs that kind of a hassle?

All joking aside, what most people dont realize is that moving a cemetery was, at one time, common. When the earliest period of Clevelands urban sprawl occurred in the 1820s, the need for housing and businesses took precedence over retaining grave sites as hallowed ground. Cemetery movements were inevitable. One thing that is immediately apparent upon seeing where these cemeteries were once located is the fact that most of them exist in what are now the more densely populated parts of the county. This further reinforces the idea that they were moved as a result of urban sprawl. Most small cemeteries that rested farther from the city have been preserved because the land wasnt needed for other purposes.

Cuyahoga Countys earliest cemeteries were little more than small, unkempt lots scattered about what would one day become a major metropolitan area. During the 1800s, most urban cemeteries were simply a place for disposing of the dead and werent treated with much respect. Few were little more than dumping grounds. Before the establishment of township cemeteries, graveyards were, for the most part, small burial plots on family farms that were later opened to neighbors. As farms changed hands, many of these cemeteries became overgrown and were lost.

Many of these grave sites have become parking lots and backyards, with a few scattered about the county in small wooded patches. Some are actually under modern homes and businesses. The question remains whether these are still cemeteries. The answer is a resounding yes. Just because you cant see the headstones doesnt mean that its not still a graveyard. With the erosion of time, tombstones fall over and settle into the grass. The changing seasons bring leaves down on them, which ultimately turn to mulch and soil. As the years pass, these headstones sink deeper into the earth until they are completely lost from sight and memory. In truth, there usually isnt much left of those who were buried in these cemeteries either, perhaps a few bones here and there.

For the most part, no visible evidence remains of these early burial sites. In some suburban and rural graveyards, small patches of creeping myrtle (Vinca minor) can still be found. This hearty plant, native to central and southern Europe, was introduced to North America in the 1700s and was commonly used as a ground cover in these old cemeteries. Though the occasional tombstone fragment might be discovered, this plant is often all that is left to indicate that a site was used as a cemetery.

For those burial grounds that were moved, there was no way for developers to know whether all of the remains had been exhumed. This was primarily due to poor record keeping and the fact that many graves were unmarked the point being, something is almost always left behind. In some cases, we can only speculate about who was buried in them. Most tombstones are either broken, missing or many inches beneath the surface. What needs to be remembered is that it is still someones final resting place and should be treated with dignity and respect.

The following pages will reveal the stories and locations of more than fifty cemeteries throughout Cuyahoga County that have been lost to the sands of time. This work is being presented to the public for many reasons, the foremost of these being the proper documentation of these locations for future reference. Should someone happen to be digging on a site and discover human bones, he or she can refer to this work and find an explanation in these pages. Furthermore, this book will tell the stories of those who once occupied this area and ultimately took their repose here. Among them are many veterans of the American Revolution, the War of 1812 and the Civil War. Some were dignitaries and famous scientists while other were people simply trying to carve out a future for their families. In all cases, their stories are fantastic and should be shared. It is also the hope that these historical sites will now be recognized for what they truly are and will one day be surveyed, documented and preserved as such. Keeping that in mind, should anyone decide to visit any of these sites, it is strongly advised that anything found there be left as it is. After all, these cemeteries have been desecrated enough, and any trace evidence that remains should be left for professionals to document and future generations to view. Take pictures and leave only footprints.

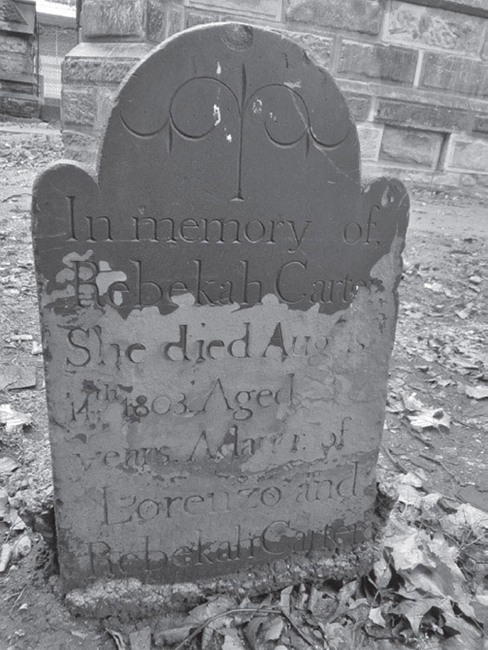

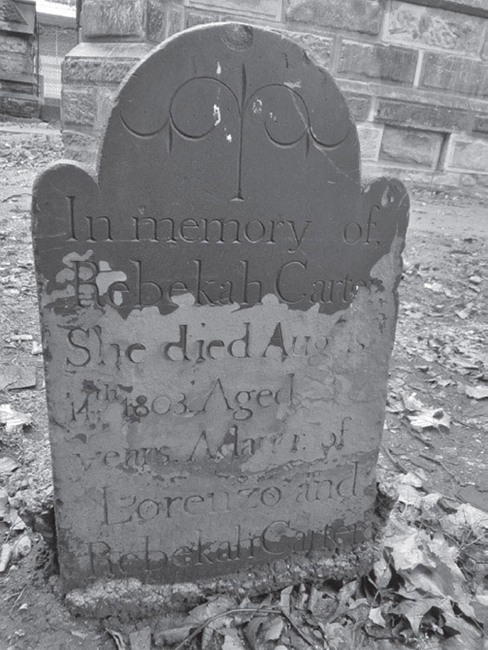

The headstone of three-year-old Rebekah Carter, who died on August 14, 1803, is the oldest in Cuyahoga County. Authors collection.

For your safety and benefit, these sites have been broken up into four classifications. The first of these is Fully Accessible. These are sites that sit on public land and can be easily visited with little or no safety hazard. The second class is Partially Accessible. These sites share their location with both public and private property. An example of this would be a site that is now occupied by a road as well as a front yard. The public side of these locations may be visited while the part that rests on private property is off limits without permission from the property owner. Next is the classification of

Next page