IMAGES

of America

GALVESTONS

BROADWAY CEMETERIES

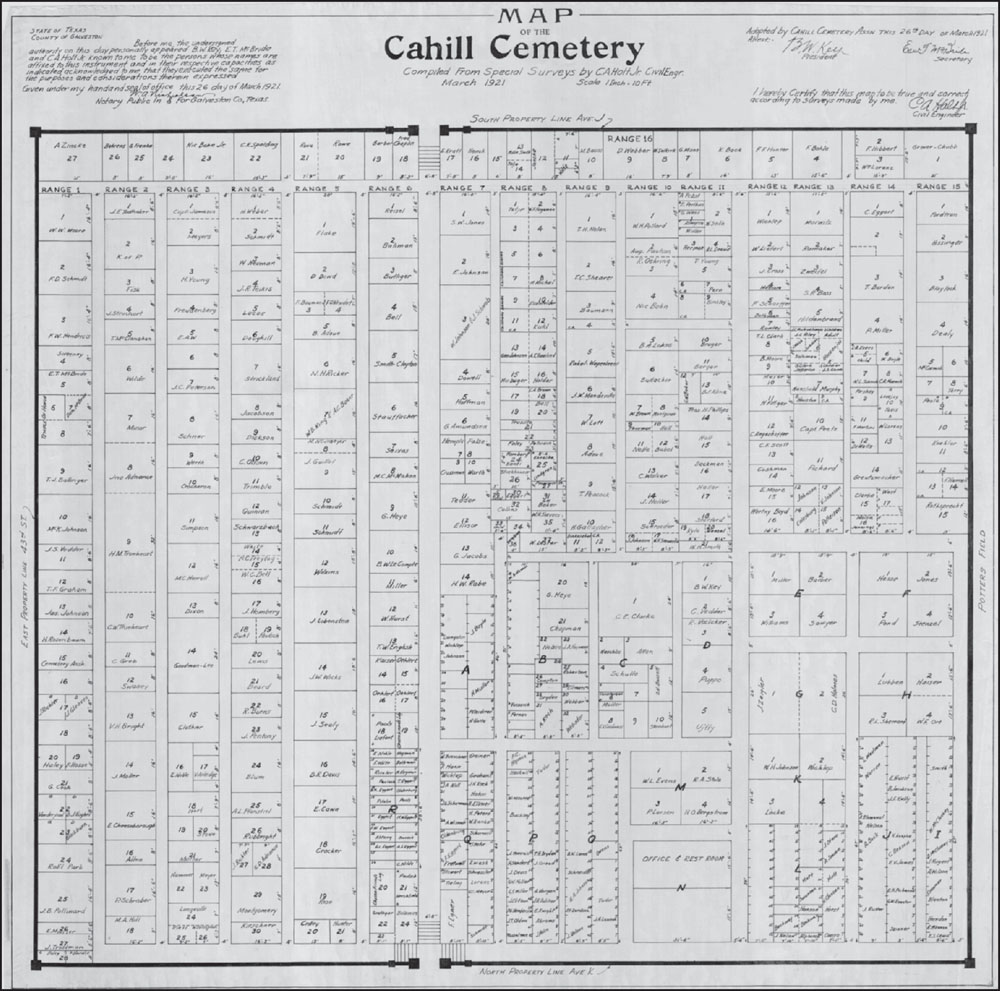

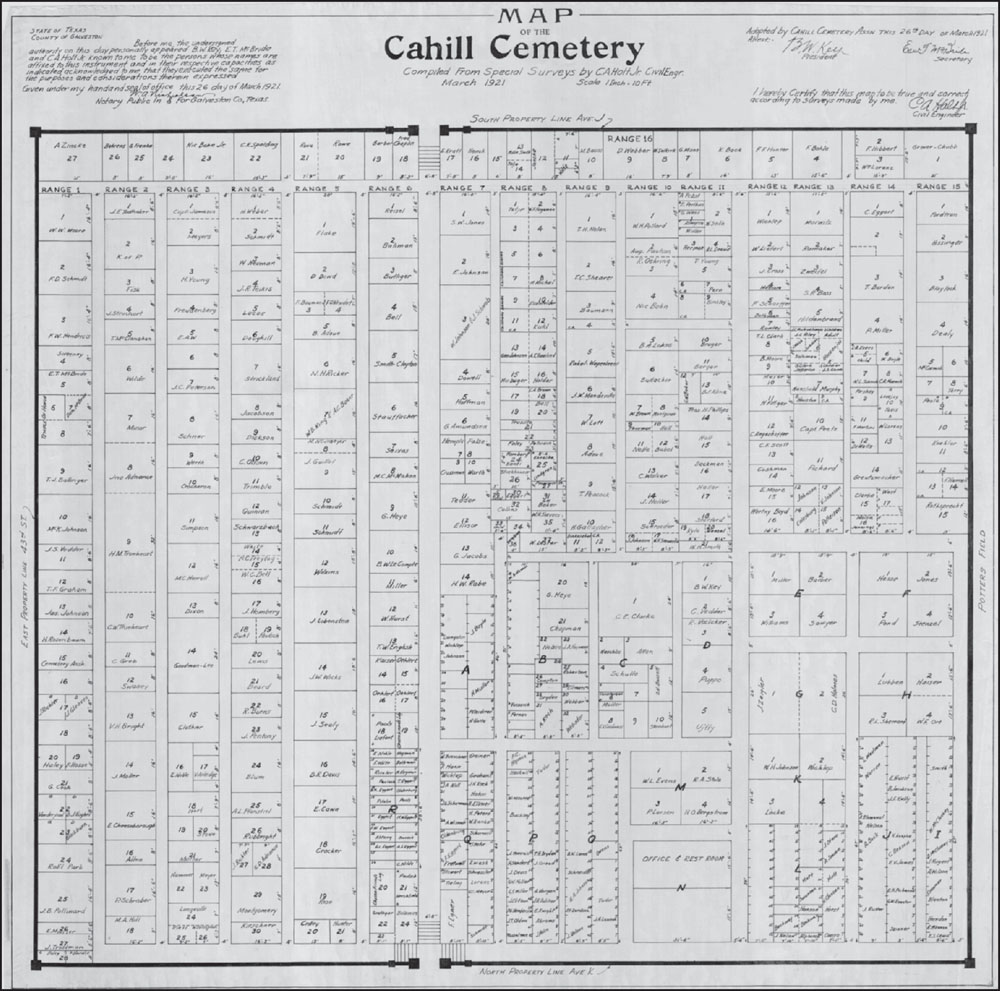

Pictured here is a 1921 map of Cahill Cemetery before the last grade raising in the cemeteries. Many names that appear on this map are nowhere to be found in the present-day lots due to grave markers being covered with fill. (Courtesy of the City of Galveston.)

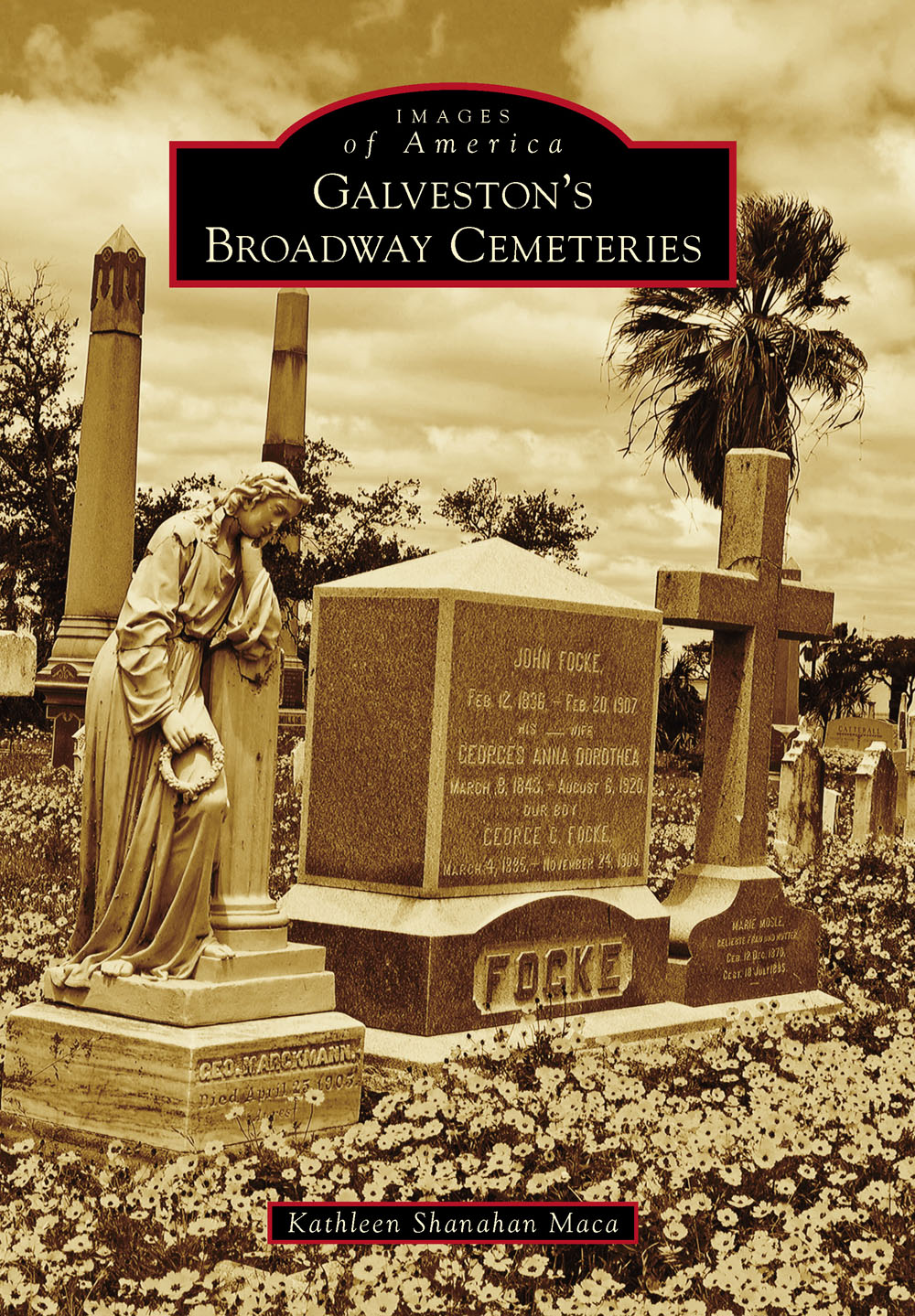

ON THE COVER: The profusion of bright yellow wildflowers makes the month of May a favorite time for photographers and visitors to explore the history hidden in Galvestons Broadway Cemeteries. (Author photograph.)

IMAGES

of America

GALVESTONS

BROADWAY CEMETERIES

Kathleen Shanahan Maca

Copyright 2015 by Kathleen Shanahan Maca

ISBN 978-1-4671-3343-2

Ebook ISBN 9781439652350

Published by Arcadia Publishing

Charleston, South Carolina

Library of Congress Control Number: 2014958538

For all general information, please contact Arcadia Publishing:

Telephone 843-853-2070

Fax 843-853-0044

E-mail

For customer service and orders:

Toll-Free 1-888-313-2665

Visit us on the Internet at www.arcadiapublishing.com

To the memory of my grandparents Juanita Haverfield Scott and Joseph Graves Noyes, who sparked my interest in history by sharing stories of the past.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This book would not be possible without the wonderful archives and institutions that generously shared their resources.

I would like to thank the Galveston and Texas History Center of the Rosenberg Library and staff members Peggy Dillard, Carol Wood, and Travis Bible for their time and patience; Catherine Gorman of the City of Galveston Planning Office; Lisa Reyna-Guerro of the Blocker History of Medicine Collections at University of Texas Medical Branch; and Trish Clason of Trinity Episcopal Church.

A special thank-you also goes out to those who shared photographs from their private collections: the Ott family, the Malloy family, Brent Scott, Lisa Smalling, Connie Saculla, and Carolyn Cannon.

Thanks are also due to Chris Smith, who shares my enthusiasm for these wonderful cemeteries and donates so much of his own time to their restoration, and Mike Kinsella of Arcadia Publishing, who was a pleasure to work with during the planning process of this book.

I am also endlessly grateful for the support of friends and family who provided encouragement during the creation of this book, especially John and Kelsey Maca, who had to live with a wife and mother who was most likely to be found wandering in the local cemeteries.

Although only a portion of the amazing stories from these cemeteries are shared here, I hope you will enjoy learning a bit about those who rest there.

A majority of the images in this volume are from the Galveston and Texas History Center at the Rosenberg Library, Galveston, Texas (GTHC) as well as the authors own photography (KSM). Also featured are selections from the University of Texas Medical Branch Galveston, Blocker History of Medicine Collection (UTMB), the City of Galveston, and the private collections of Galveston families and residents.

The following abbreviations are used to identify each grave location. This will be noted in parentheses after each caption, followed by the source of the photograph as noted above.

TE Trinity Episcopal Cemetery

OC Old City Cemetery

NC New City Cemetery

HEB Hebrew Benevolent Society Cemetery

EV Evergreen Cemetery

CATH Old Catholic Cemetery

OL Oleander Cemetery

INTRODUCTION

Old City Cemetery, established 1839

Potters Field, established 1839; renamed Oleander Cemetery in 1939

Trinity Episcopal Cemetery, established 1844

Old Catholic Cemetery, established about 1844

Old Cahill Cemetery/Yellow Fever Yard, established 1867; renamed New City Cemetery about 1900

Hebrew Benevolent Society, established 1868

New Cahill Cemetery, established about 1900; renamed Evergreen in 1923

Visitors to Galveston Island often remark on the beauty of a large cemetery they encounter after crossing the causeway onto Broadway. It is a time capsule of history that holds over 6,000 visibly marked burials within a six-block area.

What most do not realize, however, is that the complex is actually composed of seven separate cemeteries plotted together between Fortieth and Forty-second Streets, and Broadway and Avenue L.

The Broadway Cemetery Historic District is the final resting place of heroes of the Texas Revolution, political figures dating back to the Republic of Texas, both Union and Confederate soldiers of the Civil War, prominent local citizens, and more than its share of infamous characters.

One central drive with concrete walks and curbs unifies the look of the grouping of cemeteries surrounded by an iron fence. The divisions between the cemeteries are difficult to distinguish in some areas, marked only by low brick walls.

The burial grounds have a strange and interwoven history, but the beautiful necropolis was not always available to the citizens of the island.

During the early days of settling Galveston, burials were conducted in the large sand dunes that once ran the length of the side of the island facing the Gulf of Mexico. The towering dunes, covered with grass and trees, were a simple solution for family and friends who were responsible for interments of the departed before the age of funeral businesses. Hand-carved markers, often made from salvaged wood, served as headstones for loved ones.

In 1839 alone, 250 victims of a yellow fever epidemic were buried in the dunes along the beach. But the nature of sand is to shift and reshape, and markers were often covered or coffins exposed.

The citys founding fathers, owners of the Galveston City Company, alleviated this situation by donating four square blocks of land in 1839 to be utilized for public burials as part of the Galveston City Charter. Old City Cemetery and an adjacent section named Potters Field, for those who could not afford burial costs, were established the same year and became the citys first official burial grounds. The location was considered outside of the city limits at that time, a respectable distance from commercial and residential properties.

Many of the bodies previously buried in the sand hills were exhumed and reinterred at the new city cemetery, although others were discovered as they were exposed by the elements.

In 1844, two blocks of this land were deeded to local congregations: one to the Episcopal church and one to the Catholic. These became Trinity Episcopal Cemetery and Old Catholic Cemetery. Both of these cemeteries were enlarged in 1864 when the decision was made to close the section of Forty-first Street that ran between them, and the land was divided evenly.

During the Civil Wars Battle of Galveston on January 1, 1863, numerous Confederate and Union soldiers lost their lives, and many were interred in the Old City, Episcopal, and Old Catholic Cemeteries. After the war, a Confederate Potters Field was created within the existing Potters Field for veterans with no money or family to provide a formal burial.

Congress also appropriated funds for burials of soldiers and spent an estimated $3,500 on wooden headboards, picket fences, and other improvements by 1868. In addition to the 231 bodies from Galveston, soldiers remains were brought from Port Lavaca, Green Lake, and Victoria for reinterment. The government took this burial ground out of the national cemetery system in 1869 because it was unable to obtain a clear title to the land, and it soon fell into disrepair.

Next page