Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

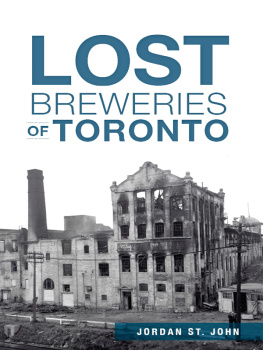

Copyright 2014 by Jordan St. John

All rights reserved

First published 2014

e-book edition 2014

ISBN 978.1.62585.199.4

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

St. John, Jordan.

Lost breweries of Toronto / Jordan St. John.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

print edition ISBN 978-1-62619-666-7

1. Brewing industry--Ontario--Toronto--History. 2. Breweries--Ontario--Toronto--History. 3. Beer--Ontario--Toronto--History. I. Title.

HD9397.C23T667 2014

338.76634209713541--dc23

2014036944

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thanks should go out to Alan McLeod, my co-author on the previous book, Ontario Beer. Thanks also to Sean Duranovich for providing images of the Dominion Brewery in operation. Thanks to Robin LeBlanc for proofreading bits of the book and for her patience with the daily research epiphanies. Thanks to the National Archive of Canada, Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library at the University of Toronto and to Larry Sherk. A book like this isnt possible without the work of pioneers like Ian Bowering and Allen Winn Sneath. Additionally, to the men and women who must have spent years archiving the nineteenth-century newspapers from the city of Toronto, I almost certainly owe you a beer. I would also like to acknowledge Jon Downing and Ron Pattinson for helping bat around contemporary brewing information.

Introduction

THE QUEEN CITYS EVOLUTION FROM 1800 TO 1914

The most helpful thing you can do to put yourself in a mindset conducive to understanding Toronto is to remember that two hundred years ago, nearly every piece of land within one hundred kilometers was completely covered with forest. It is not an exaggeration to say that only a short time ago, there were bears and wolves roaming the Don and Humber Valleys. The wilderness was vast, and the land was largely untouched. The bounty was plentiful. In some places, there were so many wild pigeons that you could simply swat them out of the air for your supper. You would not want to try that now.

Although York was not initially meant to be the capital of Ontario, John Graves Simcoes decision to use it as a makeshift administrative centre in the early days of Upper Canada would eventually cement it in that role. The capital was meant to be London, the inland position of which made it less immediately accessible to incursions by American troops. Because of the rapid growth of the town of York and its importance as a centre for trade and governance, the changeover never transpired.

The story of Torontos growth throughout the nineteenth century depends greatly on the fact that there was initially a powerful, entrenched political class of the kind that could be found in any British colonial settlement at the time. Around the powerful central oligarchic structure of the Family Compact sprang all the trade, manufacturing and agriculture that allowed the rapid growth of the city. Sometimes this happened in spite of the bureaucracy.

For most of the nineteenth century, the population of Toronto increased at a phenomenal rate, frequently doubling in a decade. Some of the citys early organizers were students of Thomas Malthus and applied the theories of his Essay on the Principle of Population to the development of York and its environs. Upper Canada sought Irish immigration long before the Great Famine. Those immigrants would drive the construction of the Grand Trunk and Great Western Railways and the settling of the frontier.

Toronto derived massive economic benefit from its position at the centre of a constantly expanding agricultural network. As a booming city, it required tradesmen of all stripes. It was not an era of specialization. Today, one might choose simply to be a brewer, and with enough talent, one might make a living at it. In Toronto of the nineteenth century, there was greater opportunity to take on additional roles. Throughout the histories related in this book, the common thread tends to be the involvement of Torontos brewers in the development of the city.

In arenas political, religious, financial and mercantile, the history of Toronto is inseparable from that of its breweries. Many of the memoirs and histories written about the city in the late nineteenth century (those of Henry Scadding, John Ross Robertson and W.H. Pearson) were penned during a period when temperance was on the march. I do not debate that some form of temperance was needed. In the early part of the century, even the Methodists were brewers, which is a very bad sign for the sobriety of a population. I will suggest to you that the mood of the city at the time shied away from acknowledging the positive contribution of the manufacture of alcohol.

The idea of Toronto the Good is bound up with late Victorian morality. It is a staid and thoroughly repressed representation that tends to whitewash the baser needs of an exploding metropolis. The flipside of that image is that of Hogtown, the grimier manufacturing and meatpacking side of Torontos heritage that helped to pay for the grand buildings that still dot our landscape. Torontos brewers occupied a space between these two realities. On a daily basis, they would encounter neighbours who occupied each. Their stories offer important insights into the development of our city.

FROM THE QUEEN CITY TO THE GREATER TORONTO AREA

If you live in Toronto, you know that one of the things that were best at is tearing down old buildings and replacing them with less historic properties. It may seem like a recent development, but I can guarantee you that this has always been the case, even if the new buildings were not always condominiums.

Over the course of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Toronto went through rapid and fairly significant changes to its layout and geography. In places throughout this history, I will need to make reference to various facets of the citys geographical development to spare you hours of poring over obscure fire insurance maps. For that reason, Im going to try and illustrate some of the core concepts that crop up frequently enough to be of universal importance.

THE GARRISON

Fort York began construction in 1793, and the museum that exists today stands on the site of the original buildings. Unlike other military fortifications within Ontario, Fort York is primarily of wooden construction, a fact that reflects the haste in which it was built. For a brief period, the administrative capital had been Niagara-on-the-Lake. It was a poor choice for a number of reasons, the greatest of which was its proximity to America.

Upper Canada had originally been part of the province of Quebec, the territory that once stretched down into the Ohio Valley and west into Michigan, Illinois and Wisconsin. The problem had been that very few people actually lived within that territory; in practice, its ownership was in some dispute. A full set of battlements like those at Fort Frontenac in Kingston would have been wasted in the towns of York or Niagara. It would have been difficult to provision and garrison. It would have been tactically inflexible. In a territory of that size, an invading army might simply go around.

Next page