Libya and the United States

Libya and the United States

Two Centuries of Strife

Ronald Bruce St John

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia

Copyright 2002 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4011

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

St John, Ronald Bruce.

Libya and the United States : two centuries of strife / Ronald Bruce St John,

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references (p.) and index.

ISBN 0-8122-3672-6 (cloth : alk. paper)

1. United StatesForeign relationsLibya. 2. LibyaForeign relationsUnited

States. I. Tide

E183.8.L75S7 2002

327.73061209dc21 | 2002018049 |

To Carol

Contents

Chapter 1

Dismal Record

Bilateral relations between Libya and the United States have been active, engaged, and positive for no more than twenty out of the last two hundred years, a dismal record with few parallels in the annals of American diplomatic history. Commercial and diplomatic intercourse between the United States and Libya began on a low note after the failure of desultory negotiations in the late eighteenth century led to armed conflict at the beginning of the nineteenth. Following a hiatus of almost a century and a half, diplomatic exchange expanded with expectation and promise, particularly on the Libyan side, in the aftermath of World War II. A little more than two decades later, relations between Libya and the United States entered the Qaddafi era, a period characterized from the outset by political tension and mutual mistrust that later deteriorated into open hostility.

No issue of foreign relations since American independence in 1776 has confounded and frustrated the policy makers of the United States more completely, repeatedly, and over a longer period of time than the problems of the Middle East. Washington has repeatedly tried and failed since 1945 to mediate lasting solutions, prevent recurrent crises, and secure its own national interests in a region that became increasingly important to the United States. The root cause of this failure was the inability of successive presidential administrations from Truman to Bush, often because of domestic political considerations, to harmonize and synthesize Americas four major interests in the Middle Eastaccess to oil, the security of Israel, containment of communism and Soviet expansionism, and adherence to the principles of self-determination and the peaceful settlement of disputes. The preservation of the status quo was the real thrust and practical intent of all four of these objectives.

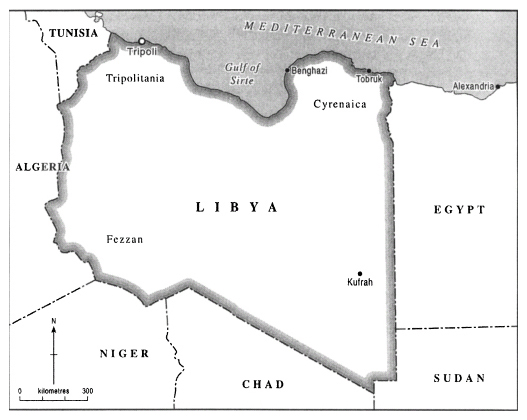

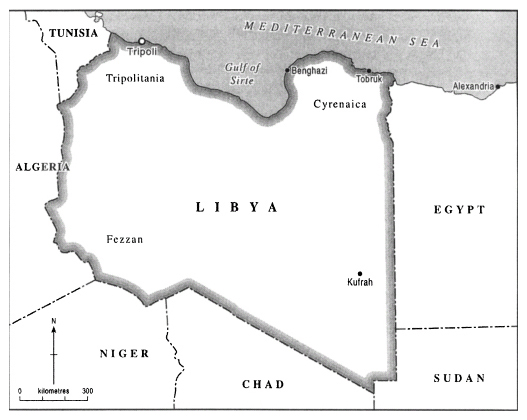

United States foreign policy toward Libya in the immediate postwar period mirrored American policy toward the Middle East and the world as a whole. In support of a Cold War strategy, grounded on a chain of air bases in the eastern Mediterranean and the Middle East, Washingtons first priority in Libya was to ensure long-term Western access to existing military facilities, especially Wheelus Field outside Tripoli. In support of this objective, the United States adamantly opposed Soviet attempts to secure similar facilities in Tripolitania. It also rejected a proposed UN trusteeship over Cyrenaica, the Fezzan, and Tripolitania because the administrator of a trust territory, under the UN system, could not establish military bases except in the case of a strategic trusteeship; and the Soviet Union was sure to veto in the Security Council any attempt to create a strategic trusteeship. As its options narrowed, the Truman administration later supported the Bevin-Sforza plan to establish a series of Western trusteeships over Libya. When this approach failed, Washington viewed an independent Libya as the best option available to achieve its strategic objectives in the region. Platitudes voiced at the time by American officials in support of self-determination and self-government were, at best, secondary considerations packaged as window dressing to disguise the real intent of U.S. policy. As the Cold War heated up, the primary interest of the United States was to secure a base agreement in Libya as soon as possible and preferably before independence strengthened the Libyan negotiating position.

With North Africa commanding the southern approaches to Europe and the western approaches to the Middle East, Arab nationalism, especially in the wake of the creation of Israel in 1948, was seen in Washington as a potent force that threatened Western interests in the region. Misreading the intent of Arab nationalists, American policy makers expressed mounting concern with the potential for communist infiltration of the region in conjunction with Arab nationalist activities. As a result, the United States, in a policy doomed from the start, opposed Arab nationalist movements in Libya for the first two decades of Libyan independence on the faulty premise that such movements would necessarily facilitate the spread of communism. In so doing, American officials throughout the 1950s and 1960s continually underestimated or ignored the potential impact of Arab nationalist movements on an isolated Libyan monarchy with transparent ties to the West. Viewing Libya after independence as a strategic asset as opposed to an important but sovereign ally, the U.S. government encouraged the regime of Sayyid Muhammad Idris al-Mahdi al-Sanusi to adopt foreign policy positions that were unpopular in the Arab world and thus contributed to the popular perception of Libya as a Western dependency. The discovery of oil in marketable quantities in the late 1950s offered an opportunity for Washington to reassess its regional policies; nevertheless, American policy toward Libya ended the decade of the 1950s exactly where it had begun.

As a result, the economic, military, and political dependence of Libya on the United States reached a dangerous level in the second decade of Libyan independence. This situation was the product of internal factors, forces, and interests in Libya together with the pursuit by the United States of its own economic, military, and political objectives. It was not the product of a Libyan commitment to Western ideals or traditions; on the contrary, the monarchy sought to minimize the impact of Western social structures and mores on the Libyan people. The Libyan government chose to maintain a close relationship with the United States and its allies because it believed they were in the best position to guarantee Libyan security. The monarchys position in this regard was later borne out in September 1969, when it asked the British government to intervene and restore it to power, an action the Labour government of Harold Wilson refused to take.

Under the circumstances, the position of the United States in Libya was rendered more and more paradoxical. As American foreign policy heightened the awareness of both governments as to the intricacy of their interests and relations, a growing number of Libyan citizens increasingly distrusted the United States and resented its extensive presence in significant aspects of Libyan internal and external affairs. The conflicting demands of Arab nationalism, and the need for ongoing cooperation with the United States to achieve many of Libyas foreign and domestic goals, contributed to the growing ambiguity that characterized this complex and convoluted relationship.