I.

II.

III.

IV.

V.

VI.

Prologue

For a student of geology, flying in a small plane for the first time from Nairobi, Kenya, down to Kigoma, a town in western Tanzania at the edge of Lake Tanganyika, must be an exciting experience. Africa can seem like a mythical, magical place to any newcomer; but for someone interested in geology, that flight from Nairobi to Kigoma is a real-life classroom lesson at one of the most spectacular geological features in the world: the East African Rift.

The Rift! Where immense subterranean forces have slowly, during the last 25 million years, ripped open a deep gash in the crust of the earth. And when, on a clear day, you ride in that small, bouncing plane southwest from Nairobi to Kigoma, you may at some point be able to imagine reaching out and down to touch the rift, which from high enough above can look like a painful wound in the planetary skin. Youll discover as well, as you begin to move above the western edge of Tanzania, a place where that great wound has filled up with water, blue and glistening, and become Lake Tanganyika. You will also recognize that the high escarpment rising up so abruptly on the eastern shore of the lake is a stressed, compressed, and eroded edge of that giant piece of torn skin.

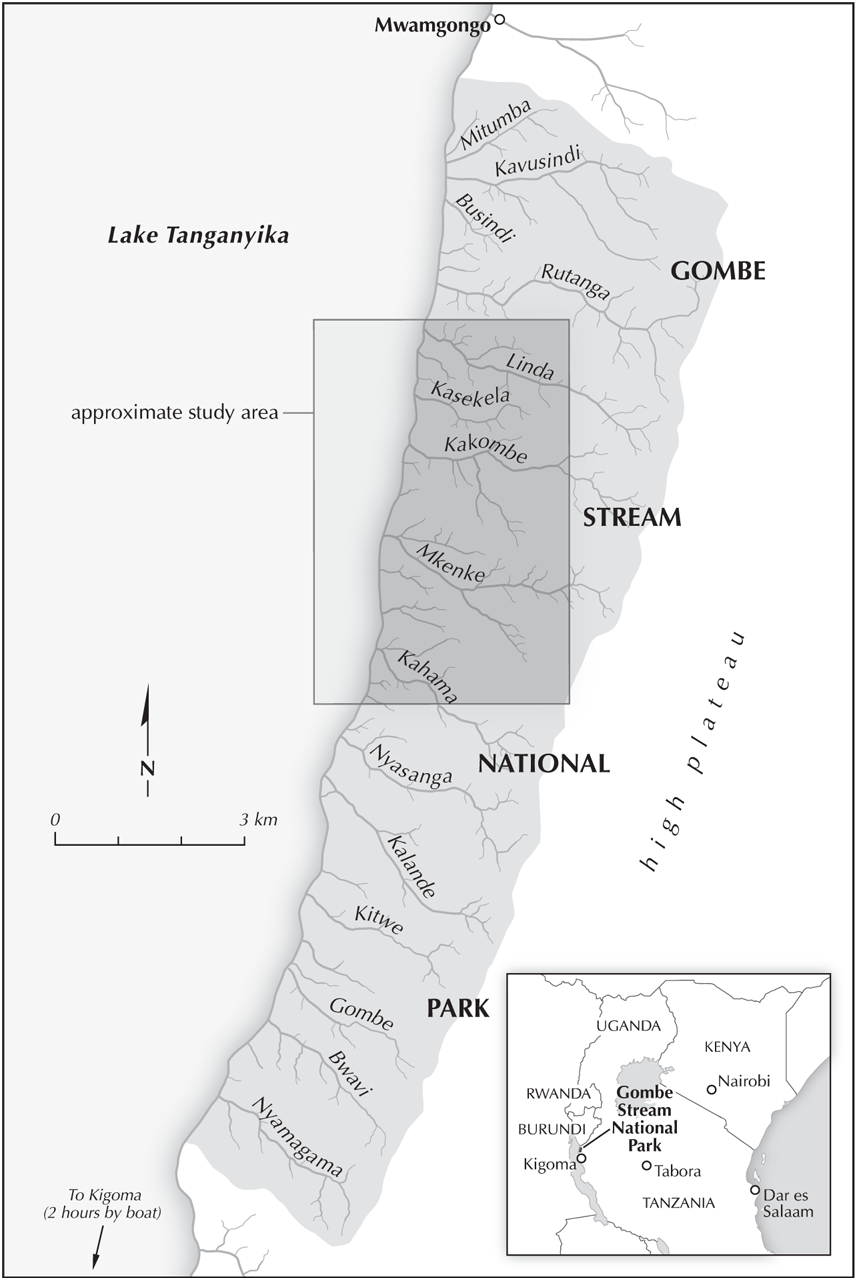

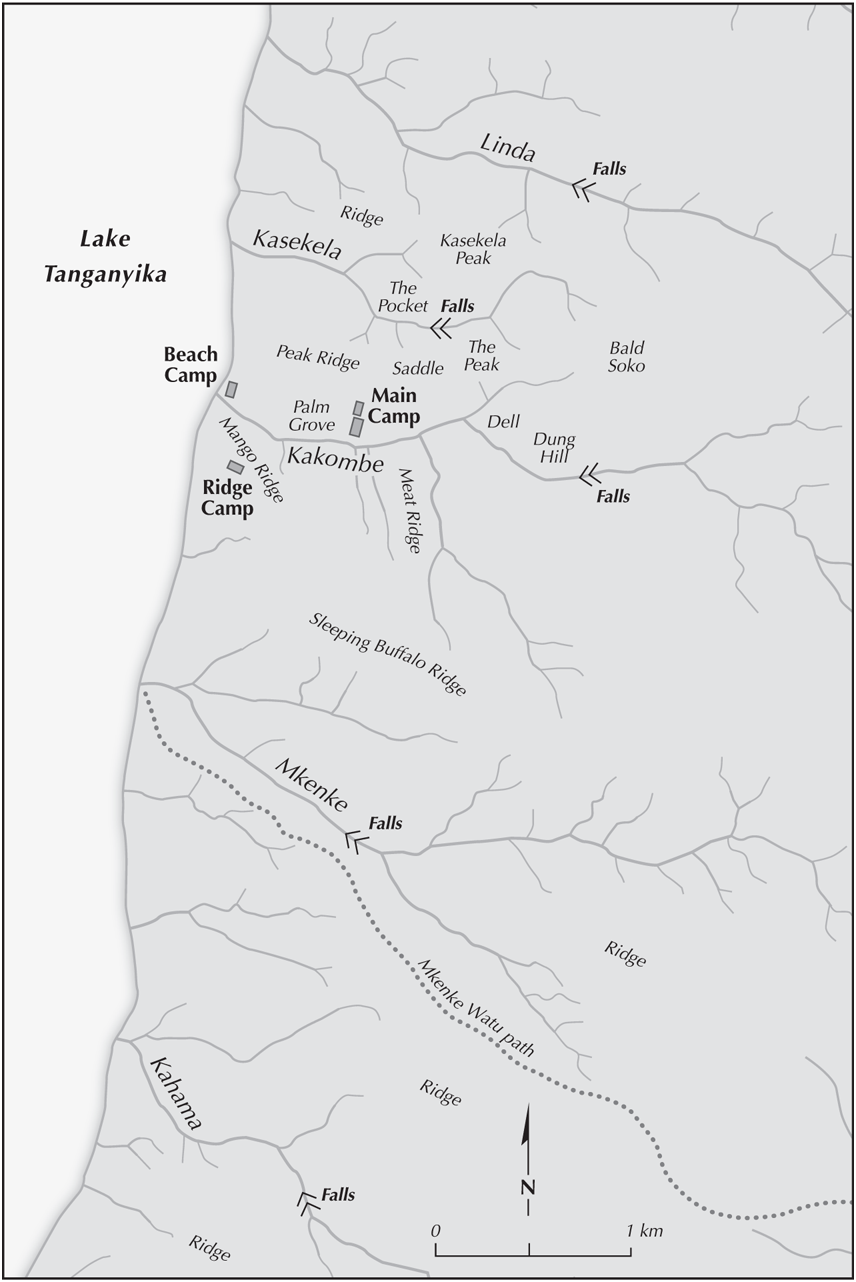

The airstrip at Kigoma is where youll land, and you can walk or be driven down to the lake and take a boat north for a couple of hours until you disembark at one of the biologically richest and best-known forests in the world: the Gombe forest, which grows right there on the rift escarpment. It is an elongated rectangle of thick and tangled vegetation situated on the rifts moving edge, with one long side lapped by the waters of the lake while the other long side extends 725 meters up a series of rough and ragged reaches to meet the high Tanzanian plateau. Gombes exceptionally rugged terrain was created by the flow of numerous streams that gather at that high plateau and descend, east to west, to the lake belowin the process, and over millions of years, scouring out numerous complex valleys. Fifteen of the streams are important enough to have been given names, which are also the names of the valleys. One of the southernmost streams is known as the Gombe Stream, which for unknown reasons has become the name of the larger ecosystem. And because the escarpment face exposes a few strata of especially hard rock, the streams tumble over cliffs and break into high waterfalls at a somewhat predictable point as they slide on their way down to the lake.

This special forest has long been protected from human intrusion not merely by its remoteness and terrain but also by cultural traditions and political decisions. The local Ha people, the Waha, may have regarded the Gombe forest as generally forbidden territory because it was said to include the sacred lairs of their formidable earth spirits. The Germans, who arrived in the late nineteenth century and claimed a good deal of East Africa as their own, formalized that early protection by defining boundaries and declaring the Gombe forest a special reserve for chimpanzees. With the collapse of the German colonial empire at the end of World War I, the British, working under a League of Nations mandate, took over the governance of Tanganyika Territory and, smartly following the German tradition, continued protecting that small rectangular forest at the western edge of their new territory, identifying it as the Gombe Stream Chimpanzee Reserve.

Tanganyika was still a British mandate and Gombe still described as a chimpanzee reserve when, in the summer of 1960, a twenty-six-year-old Englishwoman named Jane Goodall arrived. Accompanied by her mother, Vanne, and a recently hired African cook, Dominic Bandora, the young Miss Goodall pitched her tent in the forest not far from the shore of the lake and began her plan to study the chimpanzees. This improbable expedition was formally sponsored by the great paleoanthropologist Dr. Louis Leakey, but Jane Goodall had no scientific training. In fact, she had been Leakeys secretary, and she arrived at Gombe having no clear idea about how to go about studying the elusive apes. Neither, for that matter, had anyone else. No one had ever before observed wild chimpanzees to any degree, except perhaps for the one person who managed to publish a brief scientific account of them based on a few weeks of scattered observations done while crouching anxiously inside carefully constructed blinds. The precaution made good sense. As everyone knew, chimpanzees are immensely strong, emotionally volatile, and extremely dangerous.