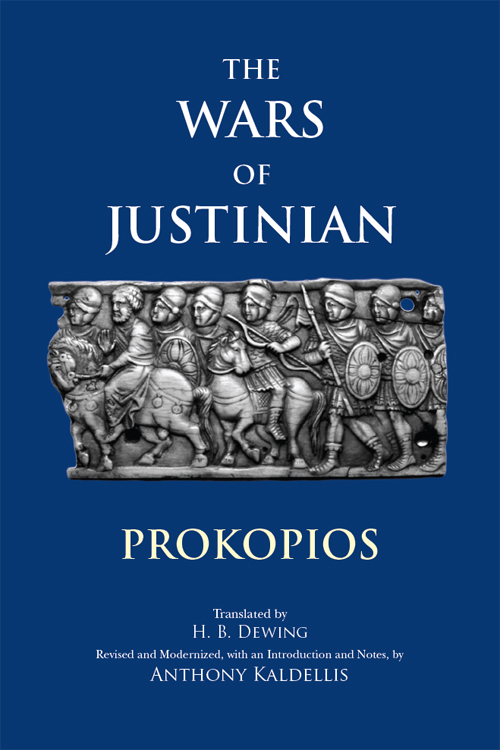

The Wars of Justinian

Prokopios

The Wars of Justinian

Translated by H. B. Dewing

Revised and Modernized, with an

Introduction and Notes, by Anthony Kaldellis

Maps and Genealogies by Ian Mladjov

Hackett Publishing Company, Inc.

Indianapolis/Cambridge

Copyright 2014 by Hackett Publishing Company, Inc.

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

17 16 15 14 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

For further information, please address

Hackett Publishing Company, Inc.

P.O. Box 44937

Indianapolis, Indiana 46244-0937

www.hackettpublishing.com

Cover design by Rick Todhunter

Interior design by Elizabeth L. Wilson

Composition by Aptara, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Procopius, author.

[History of the wars. English]

The wars of Justinian / Prokopios ; translated by H.B. Dewing ; revised and modernized,

with an introduction and notes, by Anthony Kaldellis.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-62466-170-9 (pbk.) ISBN 978-1-62466-171-6 (cloth)

1. Byzantine EmpireHistory, Military5271081. 2. Byzantine EmpireHistoryJustinian I, 527565. I. Dewing, H. B. (Henry Bronson), 1882 II. Kaldellis, Anthony.

III. Title.

DF572.P79213 2014

949.5013dc23 2014006039

ePub ISBN: 978-1-62466-173-0.

Prokopios, The Secret History. Edited and Translated. with and Introduction, by Anthony Kaldellis.

Ancient Rome: An Anthology of Sources. Edited and Translated, with and Introduction, by Christopher Francese and R. Scott Smith.

Thucydides, The Peloponnesian War. Translated, with Introduction and Notes, by Steven Lattimore.

Herodotus, Histories. Translated by Pamela Mensch. Edited, with Introduction and Notes, by James Romm.

Prokopios History of the Wars of Justinian (or simply the Wars) is one of the greatest works of history written in antiquity or Byzantium. That is not primarily a statement about its length, though it is lengthy. At 1,200 pages of printed Greek, it is longer than almost every other contemporary history that has come down to us from antiquity but it also covers a shorter time frame than most, about twenty-five years, making it the densest account of contemporary warfare. Because of this there are few periods of ancient history that we know as well in terms of their events and personalities. The Wars is written in clear, fluid classical Greek, and rarely bores or confuses the reader. It is an engaging narrative of a fascinating period of history that would otherwise have been much more obscure to us. It draws on classical literature to offer moments of Homeric heroism, Herodotean inquiry, and Thucydidean level-headedness and rhetoric. Prokopios is always in control.

The Wars is also an innovative and courageous work, two aspects that go together. The safe practice among historians of imperial Rome was to conclude their narration at the end of the previous reign, thus avoiding the choice between panegyric (flattery of the current emperor) and personal risk (telling the awful truth). Prokopios was the only one who dared to write and publish a work that covered mostly the current reign and that was generally neutral and sometimes critical of the emperor, Justinian, a ruler not known to tolerate disagreement. Prokopios reserved his most biting criticisms for a separate work, which we call the Secret History. He also experimented with structure. Justinians armies were, at times, simultaneously active in five theaters of war: northern Mesopotamia, Lazike (ancient Kolchis, modern Georgia), the Danube frontier, Italy, and North Africa. There was no precedent for writing a military history about so much going on at the same time. Prokopios tripartite solution has served historians well, though it poses difficulties too.

The events of the sixth century were momentous enough, but there is also a sense in which it was an unexpected century. It defies the logical progression from the world of the Roman empire to that of the Middle Ages and Islam. If we knew only the major changes of the fifth and seventh centuries, namely the fall of the western Roman empire and the Arab conquests, we would never postulate the resurgence of Roman power and culture in the sixth century. The fifth-century East was prosperous and relatively quiet, excepting the usual interminable theological controversies. In the sixth century it not only mobilized the resources to reconquer a large part of the West from the barbarians, once and for all codify Roman law, and build Hagia Sophia (projects attributable to Justinians initiative), it was also (no thanks to Justinian though) dynamic and innovative in its literary production, including historiography, philosophy and political thought, science, poetry (in both Greek and Latin), geography, antiquarian scholarship, theology, and hagiography. Justinian looms over this period as its main doer, Prokopios as its chief reporter.

The Wars is long enough and does not need an extensive introduction to further lengthen this volume. There is no point in giving an overview of the reign, as there are plenty of books that do that and they rely largely on the Wars anyway. The topics the work does not cover, especially Church history, are largely irrelevant to its own subject matter, which is war. This introduction, then, presents what we know about the author and a likely theory about the construction and composition of this work and its esoteric supplement, the Secret History. While Prokopios military narrative is clear enough, he does not divulge basic information about the organization of the Roman army in the sixth century, which he took for granted. This will therefore be laid out in the second section. For other topics of possible interest, such as the enemies with whom the empire was at war, the reader is referred to the guide to scholarship below.

All the facts that we know about Prokopios life come from his own writings. He was born ca. 500 in the major coastal city of Kaisareia (Caesarea Maritima), the seat of the governor of the province of Palaestina Prima. The city was a center of learning since the third century (Eusebios was its bishop in the early fourth century) and it boasted many amenities and monuments. The population of its territory was religiously mixed, including Christians of many varieties, pagans, Jews, and Samaritans. We estimate the date of Prokopios birth from his appearance in 527 as the legal advisor/secretary of the rising military officer Belisarios (soon promoted to general in 529) and the fact that he was still writing in the 550s. His movements for the period 527540 were determined by his service to Belisarios, as revealed by seemingly random glimpses in the narrative of the Wars. Before being posted to the east, Belisarios belonged to the retinue of Justinian, who was a general but resident in Constantinople. It is likely, then, that Prokopios and Belisarios met in the capital during the 520s.

![Adam Brown - World History: Ancient History, United States History, European, Native American, Russian, Chinese, Asian, African, Indian and Australian History, Wars including World War 1 and 2 [2nd Edition]](/uploads/posts/book/308581/thumbs/adam-brown-world-history-ancient-history-united.jpg)