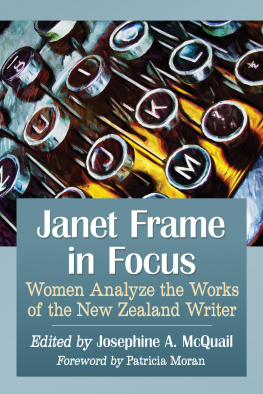

Janet Frame in Focus

Women Analyze the Works of the New Zealand Writer

Edited by JOSEPHINE A. MCQUAIL

Foreword by PATRICIA MORAN

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina

The essay Janet Frames New Zealand Autobiography: A Postcolonial Odyssey by Suzette A. Henke is reprinted from Shattered Subjects: Trauma and Testimony in Womens Life-Writing. Copyright 2000 by Suzette A. Henke, with the permission of Palgrave Macmillan Press for St. Martins Press.

The essay Janet Frames New Gothic: Language in A State of Siege is adapted from How Can Life Be Still?: Teaching Janet Frames A State of Siege and Virginia Woolfs To the Lighthouse by Josephine McQuail in Antipodes:A Global Journal of Australian/New Zealand Literature 29, no. 1, June 2015. Copyright 2015 Wayne State University Press, with the permission of Wayne State University Press.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-2854-7

2018 Josephine A. McQuail. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Front cover image of vintage typewriter 2018 itsme23/iStock

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

This book is dedicated

to the memories

of Susan Marie Chaffin,

February 16, 1958October 5, 2015,

James M. Rooney,

September 4, ?December 24, 2014,

and Marion Clavier,

October 24, 1983September 13, 2017.

The soul of Adonais, like a star,

Beacons from the abode where the Eternal are.

Percy Shelley, Adonais

Foreword

PATRICIA MORAN

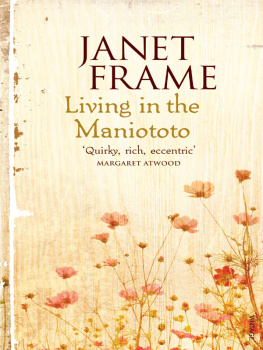

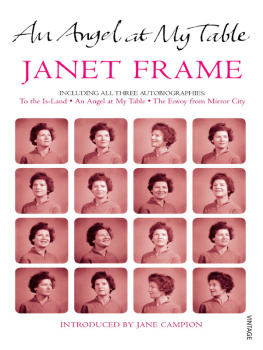

It is sadly ironic that Janet Frame may be best known today as the subject of Jane Campions 1990 film An Angel at My Table, based on Frames three-volume autobiography. In her lifetime, Frame, a prolific author, published eleven novels, three short story collections, a collection of poetry and a childrens book in addition to her autobiography. Since her death in 2004 a number of other works have been published, including a novel, a novella, several short stories, another volume of poetry, a collection of interviews and nonfiction pieces, and several volumes of letters. Yet it is her life that still dominates her reputation, specifically the tragedies that dogged her family during her formative years, her lengthy incarceration in New Zealand mental hospitals for much of her twenties, her miraculous reprieve from a lobotomy when her first collection of short stories won a literary prize, and her subsequent claiming of a spectacularly successful writing career. Mary Elene Wood relates an experience shared by many academics and scholars working on Frame: I have repeatedly had the experience in the U.S. of mentioning her name and her work to blank looks only to receive the reply, Oh, yes! when I mention Jane Campions film, Wood reports. At this point, people usually say something like, Wasnt she the one in the mental hospital? (177). As Wood points out, the film managed to place Frame once again in the light of mental illness and to spread her reputation as a mad literary artist well beyond New Zealand (177). Frame, who guarded her privacy fiercely and spent her life combatting not only the psychiatric label of schizophrenia but the tendency to read her fiction as autobiography, would be infuriated, and justly so. For as she herself often stated, her writing speaks for itself.

That writing still has not received the serious attention it merits, particularly outside New Zealand and Australia. Despite the publication of a number of book-length studies, essay collections, and journal articles, Frame remains woefully underrepresented in university reading lists and studies of postcolonial, womens and experimental writing. Study of her work has much to add to all three fields. Frames is a deeply ethical vision of the ways in which the artistic imagination informs, shapes and communicates human experiences that mostly remain inarticulated, in part because they are inadmissible by the norms of the so-called normal. Her writing thus troubles the boundaries and categories that structure social and cultural life. Yet hers is no simple deconstruction in which binary divisions are identified and upended. In giving voice to the inner lives of the silenced Frame not only endorses the vital humanity of the marginalized, but also uncovers the ways in which social and cultural norms diminish the full expression of normal humanity as well.

Frames goal is thus to show the systematic limiting of the range and richness of human experience across all categories of social and cultural organization: gender, class, nationality, yes, but also abnormality, madness, strangeness. And her means of doing so is through language. Experience for Frame is constructed and understood through language. Through formal experimentation, then, Frame challenges the acceptedthe normalconstruction of experience and meaning, and asks her readers to explore with her the uncharted territories opened up by imaginative vision. That exploration in turn expands our vision of what it means to be human even as it demands that we question what we have come to think of as reality.

Frames experimentation takes a number of different forms. Much of her fiction is metafictional, that is, fiction about the writing process itself. Here, too, experimentation serves an ethical purpose, for Frames project is always to show the process of the construction of experience, in part to expose the constructedness of the real and in part to privilege the role of the imagination in exposing that construction and positing alternative ways of thinking. One means of doing so is her manipulation of plot structure. Hence in Scented Gardens for the Blind, a novel about a couple trying to deal with a daughter who refuses to speak, the reader learns only at the end that the entire story has taken place in the mind of the mother, who is herself an incarcerated mental patient who has been mute since the age of thirty. This reversal forces the reader to rethink the meaning of madness and even speechlessness, since Veras inner worldthe entire novel, as it wereis a richly textured tapestry of relationships, observations, and sensations, one that is invisible to others but that exists nonetheless through the power of Frames rendering. In a sense this novel bears out an observation made by Istina, the protagonist of Faces in the Water, who at one point questions whether ordinary, normal thinking is preferable to the self-contained worlds of the so-called mad, whose minds she imagines to be planets in their private sky (Faces 16970) with an entire cosmogony of meaning inaccessible to others.

In other novels, multiple and shifting perspectives call into question the stability of any story, as in The Carpathians. Here the ostensible narrator tells his wifes story in the third person; her narrative is in turn usurped by a neighbor she has just met, but who presents her with a typescript in which she figures. When she escapes a seeming apocalypse, her husband conveys her surviving narrative to their son. Yet the son undermines the stability of the entire construction of the novel when he questions whether any of the narration really exists, since his parents died when he was seven. Reality is illusory: the artists imagination, like the Gravity Star that serves as a central metaphor in the novel, is the force that is capable of collapsing time and space.

Next page