Kin of Place

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

Poetry

Whether the Will is Free

Crossing the Bar

Quesada

Walking Westward

Geographies

Poems of a Decade

Paris

Between

Voices

Straw into Gold

The Right Thing

Fiction

Smiths Dream

Five for the Symbol (stories)

All Visitors Ashore

The Death of the Body

Sister Hollywood

The End of the Century at the End of the World

The Singing Whakapapa

Villa Vittoria

The Blind Blonde with Candles in her Hair (stories)

Talking About ODwyer

The Secret History of Modernism

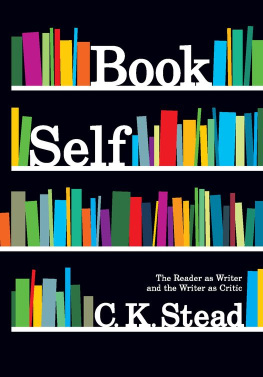

Criticism

The New Poetic

In the Glass Case

Pound, Yeats, Eliot & the Modernist Movement

Answering to the Language

The Writer at Work

Edited

Oxford New Zealand Short Stories (second series)

Letters & Journals of Katherine Mansfield

Measure for Measure: a Casebook

The Collected Stories of Maurice Duggan

Faber Book of South Pacific Stories

Werner Formans New Zealand

C. K. Stead

Kin of Place

Essays on 20

New Zealand

Writers

This ebook edition 2013

Auckland University Press

University of Auckland

Private Bag 92019

Auckland 1142

New Zealand

www.press.auckland.ac.nz

C. K. Stead, 2002

eISBN 978 1 86940 706 3

This book is copyright. Apart from fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior permission of the publisher.

Contents

Introduction

Of the twenty-eight pieces in this collection, fourteen come from In the Glass Case (1981), five from Answering to the Language (1989), and nine are new, written during 2001, a year when fiction and poetry equally left me in discontented peace. Since the earliest piece here from In the Glass Case was written in 1959, the range is across forty years, except that much of my New Zealand critical writing from the 1990s has gone into a separate book, The Writer at Work (2000), a collection in which I tried to nudge literary criticism just slightly into the field of autobiography, allowing such personal anecdotes as seemed relevant to take their place in the account.

In the present collection, though I have not set about eliminating autobiographical elements (something that would be artificial, given my own involvement over so many years on the same public stage that my subjects occupy), I have reduced it to a minimum, not reprinting, for example, any of the third section of In the Glass Case, A Poets View. Personal knowledge of the writers enters some of the recent pieces my use of Sargesons letters, for example, on the subject of his Memoirs of a Peon, and my exchanges with Allen Curnow about his last poem but these, I think, are critically useful rather than simply of human interest.

I have also kept the focus on writers, one at a time, rather than on literary movements / disputes / history; so in the case of the historical surveys, From Wystan to Carlos: Modern and Modernism in New Zealand Poetry (In the Glass Case), and The New Victorians (Answering to the Language), a short extract from the first opens the piece on Ian Wedde, and one from the second opens the Lauris Edmond article, but the essays as a whole are not reprinted. This is not because I dislike, or feel dissatisfied with, my own attempts at literary history, but in order to make a unified book, one offering views of twenty New Zealand writers each of whose work has been, is, or may be expected to be, of some literary-historical significance.

I have been through all the reprinted essays making revisions here and there, especially to those written long ago partly because the formal conventions of those years (living writers referred to as Mr or Miss) would have seemed distractingly formal, and partly because I have preferred to weed out what I now see as examples of a youthful tendency towards the emphatic and the rhapsodic. The changes are not great and make no difference either to the questions I put to myself about the poems and fictions under discussion, nor to the answers given; but the outcome is stylistically more relaxed, in keeping with my present literary self. It is clear, for example, that I am writing about Curnow at two different stages in his career, and then post-mortem; that Sylvia Ashton-Warner, and David Ballantyne, and even R. A. K. Mason, were still alive when I wrote about them and so on. Equally, despite the minor revisions, the essays will probably still declare themselves as belonging to my own early, middle or later years and that is as it should be.

Re-reading has been an interesting and in some ways a surprising exercise, reminding me again of the fact that criticism never exists in a vacuum, but is a response to what has been said, or is being said or even to a silence in which it has become imperative that something be said. Context is all; and without some reference to, some indicators of, the larger dialogue to which the particular critical statement belongs, it loses a good deal of its point. Criticism, I have always argued, should seem to come, not from God, or a committee, but from a critic. It should have individuality, character, a personality, a voice. The opinions it engages with may on some occasions have been published, at others may be no more than a murmur from the marketplace. But there should be some sense of a conversation, a community of interest.

I began writing about Curnow when his seniors, and even his contemporaries, were reluctant to concede him any sort of priority among New Zealand poets, and when he was under concerted attack from a group of poets ten years younger who felt they had been insufficiently represented in his anthologies. It may well be that the younger group were right in their complaints; but what interested me was the quality of the poetry, and in that I felt Curnows superiority was clear. It may seem obvious now no doubt it does; but there was a time when his obscurities (that was one complaint) needed to be explained away, his verbal subtleties unfolded, his capacity at once to make and to hide the larger statement illustrated.

In Baxters case there was never any such obstacle. He was from the start the marvellous boy, all generous ease and fluency, where Curnow was aloof and darkly effortful. I felt Baxters power, and resisted it; but a criticism which could not accommodate these two kinds of poetry, so capacious and so different, would have been less than useful. They were our best poets; and while there could never be a double standard (the question was sometimes raised) favouring local work, there is a sense in which, wherever you come from, the poetry of your own region speaks with a voice, an accent, and a quiver of references which make it special. To say this of Curnow and Baxter for New Zealand readers is no more significant than to say it of Yeats and Heaney for the Irish, Hardy and Larkin for the English, William Carlos Williams for Americans or Les Murray for Australians. Major poetry is international; but it usually has also a strong regional aspect, and it was regionalism which Curnow, putting together his anthologies and writing their extraordinary introductions, sometimes seemed to confuse with nationalism though it must be acknowledged that the two are difficult to disentangle.

However difficult the finer points of any such argument may be (and Curnow, as if cornered by his critics and unwilling to concede even half a point, teased them out in the direction of infinity), the importance of the local in literature is immense the more so if your region is only emerging, as ours has done over my lifetime, from a phase of colonialism in which the sense of what is real has been in some degree compromised by an inherited literature and literary history which cannot deal at all with what is immediate to hand. As I wrote in my second essay on Baxter:

Next page