THE GARDEN PARTY AND OTHER STORIES

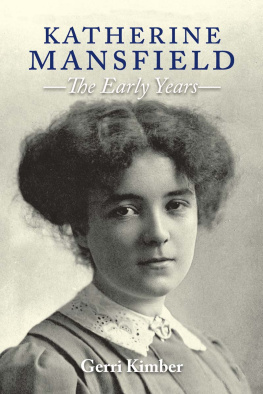

KATHERINE MANSFIELD was born in Wellington, New Zealand, in 1888 and died in Fontainebleau in 1923. She came to London for the latter part of her education, and could not settle down back in Wellington society; in 1908 she left again for Europe, never to return. Her first writing (apart from some early sketches) was published in The New Age, to which she became a regular contributor. Her first book, In a German Pension, was published in 1911. In 1912 she began to write for Rhythm, edited by John Middleton Murry, whom she eventually married. She was a conscious modernist, an experimenter in life and writing, and mixed with others of her kind, including D. H. Lawrence and Virginia Woolf. With Prelude in 1916 she evolved her distinctive voice as a writer of short fiction. By 1917 she had contracted tuberculosis, and from that time led a wandering life in search of health. Her second book of stories, Bliss, was published in 1921, and her third, The Garden Party, appeared a year later. It was the last book to be published in her lifetime. After her death, two more collections of stories were published, as well as her Letters and later her Journal.

Virginia Woolf wrote of Katherine Mansfield: She was for ever pursued by her dying, and had to press on through stages that should have taken years in ten minutes She had a quality I adored and needed; I think her sharpness and reality her having knocked about with prostitutes and so on, whereas I had always been respectable was the thing I wanted then. I dream of her often

LORNA SAGE was born in Wales, graduated from Durham and Birmingham universities, and was a Professor at the University of East Anglia. She reviewed for The Times Literary Supplement, the London Review of Books and the New York Times Book Review, and was the author of Bad Blood. She also wrote on Edith Wharton, Virginia Woolf, Christina Stead, and was the editor of Jane Bowless Two Serious Ladies for Penguin Books. Lorna Sage died in 2001.

KATHERINE MANSFIELD

The Garden Party

and Other Stories

Edited with an Introduction and notes by

LORNA SAGE

PENGUIN BOOKS

PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephens Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Mairangi Bay, Auckland 1310, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2190, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

www.penguin.com

First published by Constable and Co. 1922

This edition first published in Penguin Books 1997

Reprinted in Penguin Classics 2000

Reissued in Penguin Classics 2007

Introduction and notes copyright Lorna Sage, 1997

All rights reserved

The moral right of the editor has been asserted

Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the pubishers prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

ISBN: 978-0-14-193718-2

Contents

Introduction

Fables and fairy tales are age-old and used to be passed around by word of mouth, but short stories are a modern invention and reflect something of the loneliness of the acts of writing and reading. With the modernist movement in the early years of the twentieth century, the form took on a particularly obsessive character, and writers like Katherine Mansfield (and James Joyce and D. H. Lawrence) made short stories into intensely crafted and evocative objects-on-the-page, sometimes with nearly no plot at all in the conventional sense. Katherine Mansfield put even more into the story form than her contemporaries, however, since it was really her only form. She sometimes regretted this she joked that Jane Austens novels made modern episodic people like me look very incompetent ninnies, and said to an old friend, sadly, at the end of her life, that all shed produced were little stories like birds bred in cages. But her very dissatisfaction feeds into her stories, and gives them a special edge. And in any case, her pleasure in the form is clear. She felt at home in it, being so little at home anywhere else.

She left well-to-do New Zealand society behind in 1908 at the age of nineteen, but she remained something of an outsider in English literary circles. Her contacts with the people she met were eager, tense, competitive and mutually mistrustful. Most women in this world were helpmeets or patrons or muses or mistresses, not artists in their own right, as she wanted to be. And even in literary Bohemia the old social distinctions died hard. She was a colonial and her banker father was a self-made man, so that she fitted all too well into a certain ready-made snobbish stereotype: provincial, trade. Its possible to recapture something of the impact she made on English sensibilities by looking at her relations with the one major woman writer she knew well, Virginia Woolf. Their on-off friendship was marked by conflicting feelings of alienation and intimacy. A diary entry by Woolf for 1917, after she and Leonard had had Mansfield to dinner, reads:

We could both wish that ones first impression of K.M. was not that she stinks like a well civet cat that had taken to street walking. In truth Im a little shocked by her commonness at first sight; lines so hard & cheap. However when this diminishes, she is so intelligent & inscrutable that she repays friendship.

Even if you make allowance for Woolfs habitual private savagery, this passage shows what a powerful physical presence Mansfield had. Pioneering Mansfield scholar and biographer Antony Alpers was puzzled by Woolfs over-reaction. Katherine, he said in his 1980 Life, liked expensive French perfume (and dressed very well, for that matter). Perhaps the Woolfs thought it vulgar to wear scent at all? Alpers concluded that it must have been Mansfields passion for the life of the senses that offended Woolfs sensitive nose.

He was putting it too mildly. That civet reference is to the secretions of the musk glands of a cat, once upon a time an ingredient for making scent. Woolf was probably thinking of Shakespeares As You Like It, where bawdy Touchstone explains (Act III, scene 2) that sweet-smelling courtiers who use civet arent as clean as they seem, because civet is of a baser birth than tar, the very uncleanly flux of a cat. Put the implications together and Woolf is saying with a sort of fascinated disgust that Mansfield is like a tom-cat marking out its territory and (at the same time) a she-cat on heat. And of course the social and sexual messages are mixed up, too, so that the lines of her personality seem hard & cheap. Yet in the next sentence shes transformed into someone intelligent and inscrutable, a new kind of aloof and attractive cat who has an inner life. This was a sentiment Woolf repeated in a diary entry of 1920: she is of the cat kind, alien, composed, always solitary & observant. When she thought of Mansfield in this way Woolf felt very close to her: we talked about solitude, & I found her expressing my feelings as I never heard them expressed. She felt, she said, a queer sense of being like not only about literature; to no-one else can I talk in the same disembodied way about writing. And Mansfield wrote to her in a letter of that same year: You are the only woman with whom I long to talk work.

Next page