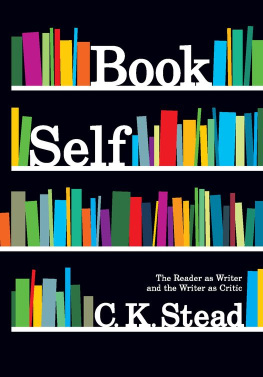

IN THE GLASS CASE

Essays on New Zealand Literature

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

poetry | Whether the Will is Free |

Crossing the Bar |

Quesada |

Walking Westward |

fiction | Smiths Dream |

Five for the Symbol |

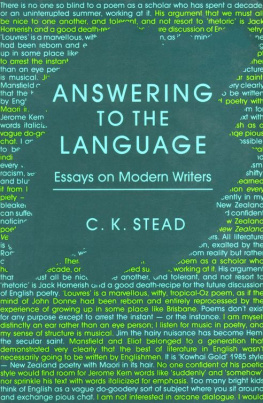

criticism | The New Poetic: Yeats to Eliot |

edited | New Zealand Short Stories (Second Series) |

Measure for Measure: A Casebook |

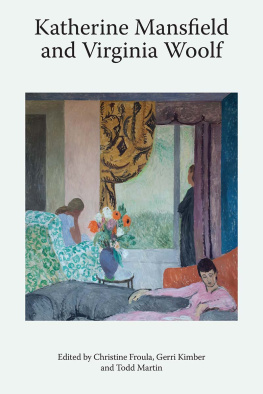

Letters and Journals of Katherine Mansfield |

Collected Stories of Maurice Duggan |

IN THE GLASS CASE

Essays on New Zealand Literature

C.K. Stead

Published with the help of a grant from the New Zealand Literary Fund

C.K. Stead 1981

First published 1981

This ebook edition 2013

eISBN 978 1 86940 705 6

Typographical design by Neysa Moss

O. E. S. / J. W. A. S.

Linflexion des voix chres qui se sont tues

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

These essays and reviews have variously appeared under the imprints of Blackwood and Janet Paul, Oxford University Press, Penguin Books, Allen Lane, and Auckland University Press, and in the periodicals Landfall, Comment, Islands, Pilgrims, The New Review (London), The Melbourne Age, and The London Review of Books. Specific acknowledgement is made at the foot of the first page of each piece.

I am grateful to all my colleagues in the English Department and to those of my colleagues in the Faculty of Arts who in 1979 supported my nomination for the University of Aucklands Senior Research Fellowship in Artsand in particular to John Asher, Sebastian Black, Keith Sorren-son, John Irwin, Bill Pearson, Keith Sinclair, Forrest Scott, Michael Joseph, Sydney Musgrove, and Donal Smith.

C.K.S.

CONTENTS

James K. Baxter

(1) A Loss of Direction (1959)

INTRODUCTION

Making this selection from reviews, review articles, and lectures published over a period of more than twenty years has made me conscious of something I also know simply from the day-to-day practice of teaching. There are few critical absolutes. However worthy of serious attention a literary work may be, there is always a variety of ways, positive and negative, of coming at it, and a good deal of the skill of the critic lies in the recognition, and then the communication, of the point of view which is the justification for the judgement he feels himself impelled to make. I say feels because there is no criticism without personal response. To be a good critic you must be practised at self-analysis. What did I feel? Why did I feel it? Is there something personal and local in that response, or would it be reasonable to assume that many literate persons would share it? Questions of that kind are the first movements towards criticism. Too many critics fail because they allow their own truest, innermost responses, which may initially be faint, to be contradicted by some doctrinaire requirement, or by the knowledge of what others have said.

Because I change, the valuation I put on various works is likely to change too. That is not to say the earlier view was wrong. Both may be justified. Many different readings of a literary work may be right (though some will be quite wrong); and many different valuations may be supported. The improvement one feels in ones own criticism is not in making better, or more sensitive judgements, but rather in getting better at seeing and making clear the grounds for judgement. In my article on John Mulgan I go to some trouble to spell out the relation between my own development as a writer and Mulgans work because I recognize quite well that Mulgan is more important to me than he will be to (say) an English or an American reader. This is not the application of a double standardan unfortunate phrase recently resurrected by Dr Cherry Hankin. For me there has never been a double standard in the sense Dr Hankin implies, of making special allowance for local work. On the contrary, I think I am in some ways more demanding of local work because I am more concerned about it. But no work of literature exists in a vacuum. There is an added dimension to the literature of any region which only those who are of that region will fully recognize. As I put it in the second of my articles on Baxter

No poetry moved me in quite the same way, at so profound a level, as our own, not just because the sensuous world it recreated was the one I knew from day to day, but because the Eden we are all cast out from is that of the world fresh to our awakening senses. For me one of the most important functions of poetry was to take us back there, and Baxter was one of the magicians who knew the way.

We must assume that there is something in Yeats which Irish readers see and feel and which we do not, however much we may revere him. That is not a double standard but the recognition that there is in most literature a regional element. Where I think a double standard may sometimes apply is against local writers. New Zealanders still (and I suppose always will) lack confidence in their own products. It is fortunate that Katherine Mansfield is as good a writer as she is because if she were worse and had the same reputation overseas, she would still be respected in her own country above all other writers we have produced. I remember in 1963 when I wrote about some of Allen Curnows poems in sentences which casually yoked them with poems by Keats and by Yeats I met disbelief, embarrassment, or laughter. I think there might now be more people in New Zealand capable of recognizing that there was nothing critically absurd or naive in what I wrote. I could see no qualitative difference between the lines I was discussing and similar lines by Keats and by Yeats, and I was right not to be cowed by the universal Kiwi demand for muted statement and hedged bets.

When I consider the body of work discussed in this book, and all the work not discussed that might have been, I have to conclude that this country has produced good literature far in excess of statistical probability. Does this acknowledgement prove that I am, after all, partial? To rebut any such statistical argument I simply put together in my mind an imaginary anthology containing (for example) a selection of Mansfield letters and journals (which I rate higher than her stories), Sargesons That Summer and En Route (early and late), some Curnow including the late sequence Moro Assassinato, some part of Duggans Rileys Handbook, half a dozen Smithyman poems, some pages from Sylvia Ashton-Warners Life in a Maori School, in part a substitute for what our society does not offer. We develop more inwardly, as individuals, less as social beings; but having done so we must launch the works which express that individuality out upon the grey tide of a society which does not really welcome it. Explaining his support for a book of Kevin Irelands which won a recent New Zealand Book Award for poetry Dr Michael Neill wrote Theres a congenially self-deprecating irony which I find particularly attractive amid so much of the inflamed egoism which seems to be our chief legacy from the Romantics. Is this a proper plea for the infusion of a long-overdue civility? Or is it merely that the old familiar suburban repression now puts on academic airs?

One of the problems of writing criticism in New Zealand is the smallness of the literary and intellectual community. To some extent we may exaggerate this. From the inside the London literary scene can also seem small. But there is no doubt that here writers are thrown together in a way which can be inhibiting to critical frankness. Also I think New Zealanders shy away from confrontations and verbal warfare, preferring to sulk and smoulder inwardly. Of course it is right not to want to inflict pain on a fellow-writer, and there is no simple formula that will cover all cases. My 1964 review of Glover was left unfinished because I found it taking a negative turnbut that was because I was leaving for a visit overseas and I felt I needed more time to reflect and to analyse. My uncertainties about Braschs poetry were muted in

Next page