Some parts of the work on this collection were done while I held the Creative New Zealand Michael King Fellowship, 200506; and final work was completed at the Liguria Study Centre near Genoa where I held a Bogliasco Fellowship in Literature in 2007. I record my grateful thanks for both these awards; and especially to my colleagues and friends at Bogliasco, and to the generosity of the Foundation there.

I make also special and grateful acknowledgement to my two brilliant editors at Auckland University Press, the late Dennis McEldowney, who edited five of my books, and Elizabeth Caffin, who has edited eight.

My thanks are due to the editors of the following journals in which some of these pieces first appeared: in the UK and Ireland, Aret, British Review of New Zealand Studies, Critical Survey, James Joyce Bloomsday Magazine, Leviathan Quarterly, London Magazine, London Review of Books, PN Review, Stand and Times Literary Supplement; in Croatia, Quorum; in France, Les Cahiers du CICLaS; in New Zealand, Christchurch Press, Landfall, New ZealandListener, New Zealand Books, New Zealand Herald, Sunday Star-Times; and to the editors of the following books: A Passion for Travel, ed. Tina Shaw; Auckland Minds and Matters, ed. Nicholas Tarling; Katherine Mansfields Men, ed. Charles Ferrall and Jane Stafford; Look This Way: New Zealand Writers on New Zealand Artists, ed. Sally Blundell; and Selected Poems of Eugene Lee-Hamilton (18451907): A Victorian Craftsman Rediscovered, ed. MacDonald P. Jackson.

C.K.S.

Think, too, that of all the arts, ours is the one that co-ordinates the greatest number of independent parts: sound, sense, the real and the imaginary, logic, syntax, and the double invention of content and form all this by means of that essentially practical, constantly changing, always dirty-fingered maid-of-all work the common language, from which we must draw a pure, ideal Voice capable of communicating an idea of self miraculously superior to Me. Paul Valry

I would like to be Mercutio [] the voice of reason amid the fanatical hatreds of the Capulets and Montagues. He sticks to the old code of chivalry at the price of his life, perhaps just for the sake of style, and yet he is a modern man, sceptical and ironic. Italo Calvino

The ego is not master in its own house. Sigmund Freud

Contents

I am sixteen years older than Martin Amis, but when I find him writing, in his foreword to The War Against the Clich, the following passage about himself when young, I feel as if we are almost contemporaries:

I was very moral when it came to literary criticism. I read it all the time, in the tub, on the tube; I always had about me my Edmund Wilson my William Empson. I took it seriously. We all did. We hung around the place talking about literary criticism. We sat in pubs and coffee bars talking about W. K. Wimsatt and G. Wilson Knight, about Richard Hoggart and Northrop Frye, about Richard Poirier, Tony Tanner and George Steiner. It might have been in such a locale that my friend and colleague Clive James first formulated his view that, while literary criticism is not essential to literature, both are essential to civilisation. Everyone concurred. Literature, we felt, was the core discipline; criticism explored and popularised that centrality, creating a space around literature and further exalting it.

Since I grew up in New Zealand, he in London, Amiss experience of this consensus was more sociable than mine, and more intense. But I remember a similar ambience, and how defining it seemed. It was, Amis suggests, the Age of Criticism. Working as a hospital orderly during one student summer vacation, and put to work in the Senile

But literary criticism, Amis goes on in that foreword, was inherently doomed. Explicitly or otherwise it had based itself on a structure of echelons and hierarchies; it was about the talent lite. And the structure atomized as soon as the forces of democratization gave their next concerted push.

You can become rich [Amis continues] without having any talent (via the scratchcard and the rollover jackpot). You can become famous without having any talent (by abasing yourself on some TV nerdathon ) But you cannot become talented without having any talent. Therefore, talent must go.

In the Age of Criticism there was a canon of great writers and great works. It was never, as later caricatured, an unchallengeable orthodoxy, an unassailable fortress. If it had been, there would have been nothing for literary criticism to do. The canon was a basis for discussion, a beginning, constantly open to challenge and constantly being adjusted. Its great usefulness was that it gave those who were reasonably well-educated (which also required talent) common ground for discussion.

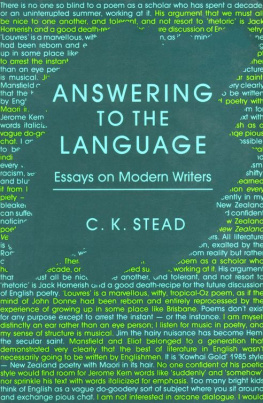

The white-anting of the canon began, alas, in the universities. Where once literary criticism had been taught and practised, literary theory, derived from France and vulgarised in America, began to take its place. Political worthiness dressed itself in a language only intelligible, if at all, to the initiated, in order at once to assert its academic credentials and to conceal its predictability and repetitiveness. Ingenuity replaced serious thought, sociological measurement replaced personal engagement, ideology replaced sensibility. Writers and writing, once the object of academic respect, were treated with a new arrogance. When I took early retirement from the university in the 1980s, after twenty years at the top of my profession, I went without regret.

Not, however, without fears for my future. It was like stepping off a secure academic perch into nowhere. As a writer in my own country I had no secure audience, nor the comfort of feeling myself one of the chaps among writers. Abroad, any credit I had was confused: was I Christina Stead (who, when a computer once corrected my first name, Christian, to Christina, was credited with all my fiction as well as her own in a list of books in print); or the author of The NewPoetic who wrote sometimes for the London Review of Books, the TLS and the London Magazine; or someone else entirely, yet to make his name?

Because I learned my trade in the period of what was called the New Criticism, and came to maturity when the dominant figure in English studies throughout the Anglophone world was T. S. Eliot, it has never at any time seemed to me that there is, or should be, a conflict or disjunction between the role of poet and that of critic. The greatest critics in English were, all of them, poets Sir Philip Sidney, Dr Johnson, Wordsworth of the Preface to the Lyrical Ballads, Coleridge, Matthew Arnold, T. S. Eliot. Every poem (and every fiction, too, which aspires to the quality of art) involves, in the writing, an unending series of critical decisions. The choice of one word over another, the sound of that word in relation to others around or near it, the tone of voice, the degree to which meaning is revealed and concealed for effect and whether it can be enriched by doubleness or ambiguity, the observance or avoidance of rhyme, of form, of metaphor and imagery these and innumerable other choices are being made and remade, reconsidered and revised, in the course of composition. And all this must be held together, must not fall into fragments. In fact it can seem that so much is going on, control of the process must be beyond consciousness hence the idea of poetic inspiration and the mythologies of the Muse. But inspiration, I became convinced, though real (nothing with such a strong tradition should be lightly dismissed), and often beyond the poets conscious control, was only a speeding up of the process. It was not driving blind but, more likely, a kind of