ON EMPSON

ON EMPSON

WRITERS ON WRITERS

Philip Lopate | Notes on Sontag

C. K. Williams | On Whitman

Michael Dirda | On Conan Doyle

Alexander McCall Smith | What W. H. Auden Can Do for You

Colm Tobn | On Elizabeth Bishop

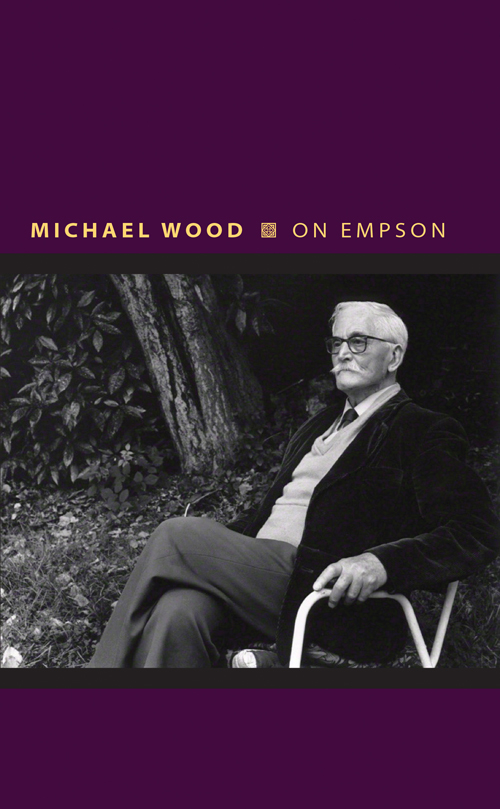

Michael Wood | On Empson

MICHAEL WOOD  ON EMPSON

ON EMPSON

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

Princeton and Oxford

Copyright 2017 by Michael Wood

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to Permissions, Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR press.princeton.edu

Excerpts from Arachne, Villanelle, This Last Pain, To an Old Lady, Note on Local Flora, Aubade, Autumn on Nan-Yueh, Anecdote from Talk, Chinese Ballad, and Let It Go, from The Complete Poems of William Empson, edited by John Haffenden, copyright 2000 by the Estate of William Empson, are reproduced with permission of Curtis Brown Group Ltd, London, on behalf of The Beneficiaries of the Estate of William Empson.

Jacket image courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery Picture Library

All Rights Reserved

ISBN 978-0-691-16376-5

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016955220

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Minion Pro and Myriad Pro

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Elena

For Elena

CONTENTS

CONTENTS

ON EMPSON

ON EMPSON

ONE

Empsons Intentions

What is a hesitation, if one removes it altogether from the psychological dimension?

Giorgio Agamben, The End of the Poem

I

There is a moment in William Empsons Seven Types of Ambiguity when he decides to linger in Macbeths mind. The future killer is trying to convince himself that murder might be not so bad a crime (for the criminal) if he could just get it over with. This is about as unreal as a thought could be, coming from a man who seems to have been plotting murder even before he allowed himself consciously to think of it, and whose whole frame of mind is haunted by what he calls consequence, the very effect he imagines it would be so nice to do without. The speech begins

If it were done when tis done, then twere well

It were done quickly: if the assassination

Could trammel up the consequence, and catch

With his surcease success

Empson takes us through the passage with great spirit, commenting on every line and its spinning, hissing meanings, and then alights on a single word:

And catch, the single little flat word among these monsters, names an action; it is a mark of human inadequacy to deal with these matters of statecraft, a child snatching at the moon as she rides thunder-clouds. The meanings cannot all be remembered at once, however often you read them; it remains the incantation of a murderer, dishevelled and fumbling among the powers of darkness. [ST 50]

It is an act of alert critical reading to spot the action word among the proliferating concepts, especially since it names only an imaginary act; and generous to suggest that Macbeth, crazed and ambitious as he is, even as he contemplates the killing of his king, can still represent a more ordinary human disarray among matters that are too large, too consequential for us. Alert too to see that Shakespeare represents this case not only dramatically but also through his characters choice of an individual word. But then to call the other words monsters, to identify the small verb as a child, and to introduce the moon and the thunderclouds, is to create a whole separate piece of verbal theatre, and to produce something scarcely recognizable as criticism. And when at the end of the quotation Empson widens his frame, returning to Macbeths full, anxious meditation, he continues the same double practice. He turns our failure to grasp all the meanings into an achieved Shakespearean effect and not a readerly shortcoming, and he finds a figure of speech for the character and the situation. The word becomes a whole passage, the child becomes a fumbling and disheveled magician, and the moon and thunderclouds become the powers of darkness.

What is happening here? Empson would say, too modestly, that this is descriptive criticismas distinct from the analytic kind. But he is not describing anything. It is not impressionistic criticism either, an attempt to evoke the feelings the work has aroused in the reader, although this is closer to the mark. Empson is tracing a pattern of thought, and finding metaphors for the behavior of a piece of language. William Righter, thinking of such effects, speaks of narrative substitution, and of a critical style which has the form and manner of paraphrase, but is really a caricature [Righter 72, 68]. This seems perfect as long as we regard the caricature as both lyrical and inventive, an enhancement of the text rather than a mockery of it, a simplification that also complicates.

Empsons writing reminds us (we do forget such things) that characters in plays are made of words, they are what they say, or more precisely they are what we make of what they say, and his metaphors bring the life of these words incredibly close to us. The child snatches and Macbeth fumbles, but the child is herself a verb, and Macbeth is a man using words to keep his mind away from a deed.

I thought of this passage on the one occasion when I saw and heard Empson. He was giving the Clark Lectures in Cambridge in 1974. What I mainly remember is his waving about a piece of paper on which he had some notes, not lecturing so much as commenting on what had come up in the office hours he had held the week before in Magdalene College, the place from which he was once expelled. Much of the material was fascinating, if disorderly, but I was struck more than anything else by the energy and the chaos of what he was saying, and the sense that he found the questions that he had been asked or that had occurred to him in his conversations far more interesting than whatever he had prepared as a lecture. Recorded reports of the event come close to my memory, but have a different tone. George Watson says Empson didnt mention the names of anyone whose work he was objecting to, just said Oh, Im sure you know who they are. Leo Salingar says Empson rambled on interminably [Haffenden II 562]. I did wonder if Empson was entirely sober, but I still felt the passion and the mind in play, and there was something wonderfully tireless about the performance, as if talking avidly about literature and life was the best thing anyone could be doing. He was trying to find his way among a crowd of ideas, and didnt know which to look at first or for how long. And I suppose I already thought that he might have his own forms of dishevelment.

For these and other reasons I see the Macbeth passage not as a modelwho could follow it?but as a spectacular instance of what criticism can do, of how personal and imaginative it may be while remaining very close to the text. If it doesnt look like much of the criticism we know, it is because it isnt.

Next page

ON EMPSON

ON EMPSON