FOR ALL HIS EDITORS

CONTENTS

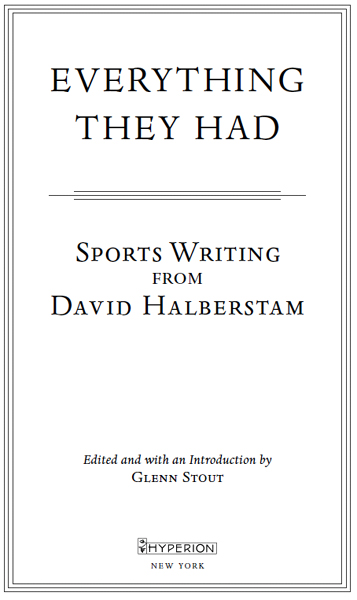

Many readers may be surprised to discover that as an undergraduate at Harvard University, David Halberstam, who would become the most honored journalist of our time, began his journalism career in the press box. As a staff writer for the Harvard Crimson he covered intramural basketball and the freshman baseball team before matriculating to varsity football. For a time he even wrote a sports column for the Crimson inventively titled Eggs in Your Beer. One of the pleasures of editing this volume has been the discovery that over the ensuing five decades, through stints at newspapers in Mississippi and Tennessee and the New York Times, and assignments in the Congo, Vietnam, Poland, and Paris, and then after leaving daily journalism to write books, he never strayed from the sports page for long. While working for the Nashville Tennessean from 1956 through 1960 he once covered opening day of the baseball season and reported on a high school student who would soon win several Olympic medals named Wilma Rudolph. After he joined the New York Times in 1960, his first byline for the Times was not about any great issue of the day, but, of all things, about a ski jumping exhibition held in late November on man-made snow at Central Parks Cedar Hill.

This is, I think, telling. He once wrote of his sports titles that [they] are my entertainments, fun to do, a pleasant world and a good deal more relaxed venue, less pressured and more enjoyable than his heavier and more lengthy books about what he termed society, history and culture. Yet I do not think he viewed writing about sports as necessarily something lesser, for he also wrote that sports were a venue from which I can learn a great deal about the changing mores of the rest of the society. He recognized that sports are important because sports matter to people, and that sports, and how we relate to sports, say something of value about ourselves, our society, and our history and culture, one of the rare places where citizens of differing creeds, classes, and races come together.

David Halberstam was, at his core, a reporter, and even when he was writing about sports he was reporting on the worldthey were not separate. In a story he wrote as an undergraduate for the Harvard Alumni Bulletin about sculling on the Charles River, the first story reprinted in this book, he also managed to capture a bit of the Cold War fear that was then wreaking havoc upon the postwar psyche. His brief report on Wilma Rudolphs track squad provided Halberstam himself with a lesson in racial progress, or the lack thereof. His editor excised his use of the term coed in his description of the runnersat the time the term was reserved for white students only.

This background in sports does not make David Halberstam particularly unique. A number of great American writers were, at one time or another, sportswriters, ranging from Ernest Hemingway to Jack Kerouac, Hunter S. Thompson, James Reston, and Richard Ford. What is unique, however, is that David Halberstam, while moving beyond sports, did not, I think, move past sports. While he never elevated sports out of proportion, sports never ceased to be important to him and he never cast sports aside as insignificant, once writing that I do not know of any other venue that showcases the changes in American life and its values and the coming of the norms of entertainment more dramatically than sports.

One reason that he felt that way may be because he found those who wrote about sports among the best teachers of writing in all journalism. In his introduction to a collection of work by W. C. Heinz entitled What a Time It Was, Halberstam credits Heinz, who is best known for his sportswriting, as one of those people who made me want to be a writer, someone who helped teach me what the possibilities of journalism really were. Gay Taleses famous profile of Joe DiMaggio, The Silent Season of the Hero, written in 1966 for Esquire, had a similar impact. For Halberstam, Taleses sober, nuanced portrait of DiMaggio simultaneously exposed the limits inherent in newspaper journalism and the creative possibilities of magazine work, which promised what Halberstam called the greatest indulgence of all for a journalist, the luxury of time. Over the years he regularly noted the influence of other writers like Red Smith, Jimmy Cannon, Jimmy Breslin, Murray Kempton, and Tom Wolfe on his own work. Smith, of course, was a sports columnist, and while Breslin, Cannon, Kempton, and Wolfe wrote of many topics, all considered sports a valid subject upon which to exercise their unique creative talents.

It was, in fact, the influence of these talented writers that caused Halberstam to look at his own work and career and, shortly after Taleses story about DiMaggio appeared in print, to ponder leaving daily journalism. Despite winning the Pulitzer Prize in 1964 for his reporting on the Vietnam War, he began to find daily journalism too rigid and confining.

His frustration with daily reportage and his desire to say more is apparent even in his earliest work and is apparent even when he wrote about sports. In March of 1961 Halberstam wrote a brief story for the Times about the Washington Redskins new football stadium, which was being built as part of the National Capital Parks system and therefore fell under the jurisdiction of the Interior Department. In the story, U.S. Interior Secretary Stewart Udall warned Redskins owner George Preston Marshall, a notorious bigot who at that point had yet to put an African American player on the field in a Redskins uniform, that if he continued to discriminate in his hiring practices, the new stadium might not be available to the Redskins.

The story is unremarkable except for the ending. Halberstam interviewed both Udall and Marshall for the story, and the Redskins owner offered up his usual excuses for not employing any African Americans, telling Halberstam that Redskins fans were mainly from the south and therefore the team recruited players from southern universities, which just so happened to field all-white football teams, a transparently cowardly posture that ignored the fact that there were already African American collegiate players in black colleges as well as African American players in the NFL available by trade. Yet Marshall told Halberstam, I dont know where I could get a good Negro player nowthe other clubs arent going to give up a good one.

Reading the story today, one can almost feel Halberstam bristling at Marshalls unapologetic bigotry and insensitivity. As the reporter of a news story, he simply did not have the latitude to take Marshall directly to task on the topic, an experience he must have found frustrating.

Yet still, he did find a waythrough simple reporting. Immediately following Marshalls quote, Halberstam added one single, concise fact, one small take that of a sentence that said everything, writing simply, The Redskins won only one game last year and finished last in their division.

Several years later, when Halberstam was serving as a foreign correspondent for the Times in Warsaw, Poland, the paper sent staffers a memo requesting that they write stories exactly 600 words long. In response Halberstam wrote his now famous letter to his fellow correspondent and former staffer at the

Next page