In memory of Dr. Michael Halberstam (19321980), who in the last year of his life was fond of sneaking onto Washington, D.C., playgrounds and attaching brand-new nets, which he had just bought, so that he and other playground players could hear their jump shots swish; and for his wife, Elliott Jones, and his sons, Charles Halberstam and Eben Halberstam.

Contents

Fame, O.J. said, walking along, is a vapor, popularity is an accident, and money takes wings. The only thing that endures is character.

Whered you get that from? Cowlings asked.

Heard it one night on TV in Buffalo, O.J. said. I was watching a late hockey game on Canadian TV and all of a sudden a guy just said it. Brought me right up out of my chair. I never forgot it.

From an article by Paul Zimmerman,

Sports Illustrated, November 26, 1979,

on O. J. Simpson

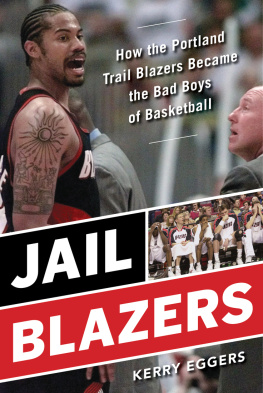

National Basketball Association franchise established in Portland, Oregon, in the fall of 1970, principal owner Herman Sarkowsky, minority owners Bob Schmertz and Larry Weinberg.

197071: | Won 29, lost 53. Coach: Rolland Todd. Geoff Petrie is first-round draft choice. Season ticketholders: 1,095. |

197172: | Won 18, lost 64. Coach: Rolland Todd (fired in midseason) 1244; then Stu Inman (who finishes season) 620. Sidney Wicks is first-round draft choice, Larry Steele third-round. Season ticket-holders: 2,227. |

197273: | Won 21, lost 61. Coach: Jack McCloskey. LaRue Martin first-round draft choice, Lloyd Neal third-round. Season ticketholders: 2,410. |

197374: | Won 27, lost 55. Coach: Jack McCloskey (let go at end of season). No important draft choices. Season ticketholders: 2,971. |

197475: | Won 38, lost 44. Coach: Lenny Wilkens. Assistant coach: Tom Meschery. Bill Walton first-round draft choice. Season ticketholders: 6,218. |

197576: | Won 37, lost 45. Coach: Lenny Wilkens. Draft choices: Lionel Hollins (first-round), Bobby Gross (second-round). Larry Weinberg becomes principal owner. Season ticketholders: 6,561. |

197677: | Won 49, lost 33. Coach: Jack Ramsay. Assistant coach: Jack McKinney. Maurice Lucas, David Twardzik arrive from ABA. Herm Gilliam arrives in trade. Trail Blazers win NBA championship in six games with Philadelphia. Season ticketholders: 8,103. |

197778: | Won 58, lost 24. Coach: Jack Ramsay. Playing the best basketball in their history, the Blazers are 5010 when Bill Walton is injured. Partially recovered, he subsequently breaks his foot in the second playoff game with Seattle. Walton then asks to be traded. Tom Owens joins team after trade with Houston Rockets. T. R. Dunn, second-round draft choice, replaces Herm Gilliam. Season ticketholders: 11,500 (ceiling set by club). |

197879: | Won 45, lost 37. Coach: Jack Ramsay. Walton sits out entire season with injured foot. Draft choices: Mychal Thompson and Ron Brewer (both first-round). Season ticketholders: 11,500. |

In the week before the first practice they began checking into the small motel near the base of Mount Hood in the small suburban community of Gresham, Oregon. They were rookies and free agents, and the odds were already against them; their motel rooms were paid for, and there was daily meal money, but in a profession where more and more things were guaranteed, they were still at the point in their careers where the only thing guaranteed was a return airplane ticket back home in the likely event they were cut. The veterans, the young princes of the sport, who all owned homes in the swank upper-middle-class sections of Portland, were not required to arrive until the last moment, as befit their superior status. In contrast to the rookies and the free agents, the anxiety level of the veterans was relatively low; they had made the team before, many had even played on a championship team, and most important of all, the money in their contracts was guaranteed. For the rookies and the free agents it was another thing. Now, in the fall of 1979, they were at the very brink of their dreams, which was to play under contract in the National Basketball Association.

It was an odd and unlikely collection. Steve Hayes was white and very tall, 611. He also shot well, and once upon a time in this game that had been enough, to be tall and have a light shooting touch; but the game had now become one of speed and muscle, and Steve Hayes was lacking in both categories. He knew the coaches thought he was slow (intelligent but very slow was in fact their precise definition of him) and that in contrast to many of the muscular young blacks with whom he would be competing, his body lacked muscle tone. What he did not know and what would have given him some momentary cause for optimism, was the fact that the teams consulting psychologist, who had just tested him, was very impressed, not by Hayess jump shot or court intelligence but by his psychological coherence. The shrink had become, because of that, a secret Steve Hayes booster, mentioning Hayess name frequently to the coaches, prefacing his remarks with the disclaimer that he of course did not know basketball, but then adding very quickly that psychologically Hayes was sturdy, very sturdy indeed, a good bet for the NBA, psychologically speaking.

Steve Hayes had been through all this once before, in 1977, at a preseason camp run by the New York Knicks. Arriving as a fourth-round draft choice, he had been judged too slow and had gone on to play for two years in Italy. He believed he had now spent enough time in the minor leagues. He also knew just how many players there were ahead of him on the Portland roster, and which of them had guaranteed money, and understood that the odds against him were already immense. Coaches who had once coveted bodies like his no longer did. All that made him feel slightly less than sturdy just then.

Hayess feelings were a good deal more tranquil, however, than those of another free agent named Greg Bunch. Bunch, who was black and quick while Hayes was white and slow, was at the moment still in a rage over what had been done to him earlier in the day. Greg Bunch had undergone the same battery of psychological exams that illuminated Steve Hayess coherence, but, by mistake, had been required to undergo them a second time. That had convinced Bunch, who mistrusted professional basketball management anyway, that they were trying to mess with his head. He had exploded and started screaming at the team trainer, who was administering the test, to leave his head alone. Bunch had some reason for grievance in his professional career; a year earlier, as a second-round draft choice with the New York Knicks, he had played well in the preseason camp, had made the team, had even played in twelve regular-season games (averaging roughly eight minutes and two points a game) before being released in what was widely regarded as a racial decision. The Knicks, it appeared, wanted to keep the tail end of their bench a little whiter. Greg Bunch, bruised many times in his brief professional career, was duly sensitive and duly wary of the great white they who controlled his athletic destiny.

Bunchs roommate, a young black man from Racine, Wisconsin, named Abdul Jeelani, thought he had never seen anyone so tight. They were competing for the same job, small forward, on a team that already had two small forwards, both white; and it was a mistake, Jeelani thought, for the club to make them roommates. Jeelani had been at rookie camp earlier in the summer with Bunch and Bunch had refused to talk to him; then they had both been in the Los Angeles summer league for a month, and again Bunch had made a point of not speaking to Jeelani. Now here they were on the eve of the start of fall camp, with the veterans arriving the next morning, and they were rooming together. For the first time, Bunch was willing to say a few guarded words to Jeelani, a very few words indeed. They did not go out to eat together; there was too much tension in the air for that. Jeelani preferred in any case to eat out with Steve Hayes, whom he had known and played against in Italy. But he worried about Bunch, who was so tight that he could not sleep at night, always tossing and turning in bed. Jeelani in one sense wanted to befriend Greg Bunch, but he was aware, in the most primitive way possible, that everything good which happened to Bunch was bad for Abdul Jeelani. It was terrible to think that way. So he kept his distance from Bunch. At the same time he couldnt help realizing that the fear and tension in the face of his roommate was the same fear and tension he had seen on his own face during his three previous NBA tryouts, in Detroit, in Cleveland, in New Orleans, when he had looked around him and become convinced that everyone there, rookies, veterans, coaches, scouts, wanted him to fail. At this camp Jeelani felt more confident, more mature. He had three years of European ball behind him and he knew that only one playerJimmy Paxson, a guard and thus not a competitorhad guaranteed money.