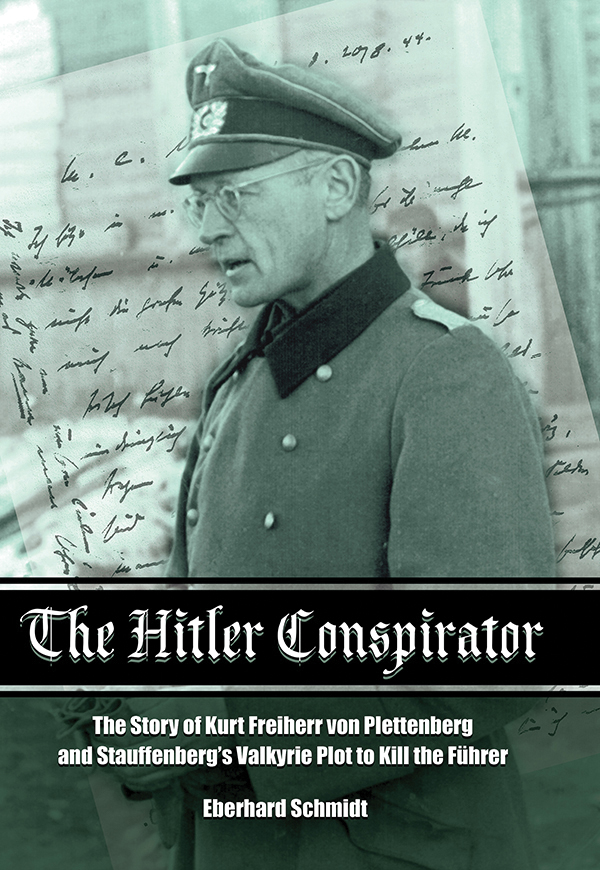

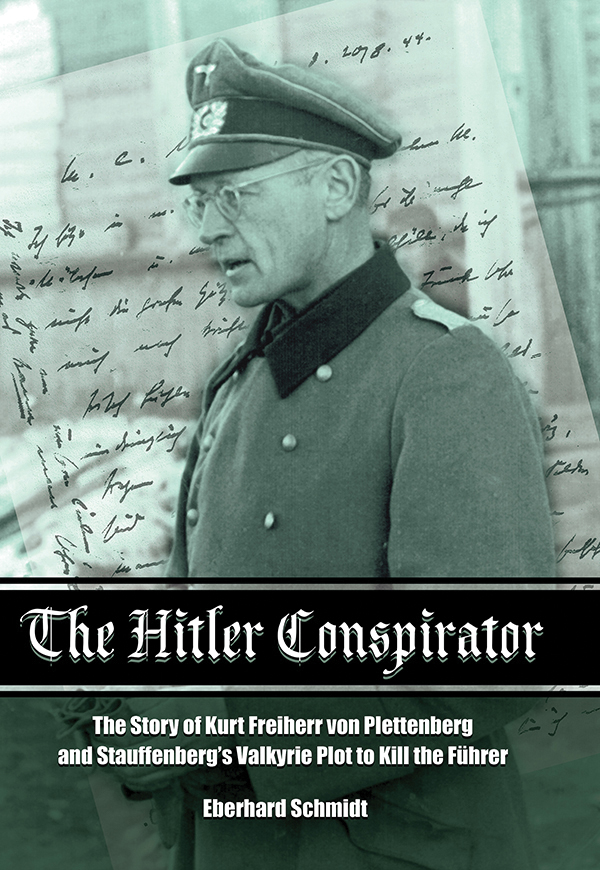

The Hitler Conspirator

The Hitler Conspirator

The Story of Kurt Freiherr von Plettenberg and Stauffenbergs Valkyrie Plot to Kill the Fhrer

Eberhard Schmidt

With the assistance of

Dorothea-Marion von Plettenberg and

Karl-Wilhelm von Pletteberg

Foreword by

Peter Hoffmann F.R.S.C.

Translated by

Cordula Weschkun

THE HITLER CONSPIRATOR

The Story of Kurt Freiherr von Plettenberg and Stauffenbergs

Valkyrie Plot to Kill the Fhrer

Original German language edition entitled Kurt von Plettenberg. Im Kreis der Verschwrer um Stauffenberg Ein Lebensweg , published by F.A. Herbig

Verlagsbuchhandlung GmbH in 2014.

This English edition first published in 2016 by Frontline Books

an imprint of Pen & Sword Books Ltd,

47 Church Street, Barnsley, S. Yorkshire, S70 2AS

www.frontline-books.com

Copyright 2014 by F.A. Herbig Verlagsbuchhandlung GmbH, Mnchen.

All rights reserved.

Translation copyright Frontline Books, 2016

ISBN: 978-1-47385-691-2

eISBN: 978-1-47385-692-9

Mobi ISBN: 978-1-47385-693-6

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

CIP data records for this title are available from the British Library

For more information on our books, please email:

,

write to us at the above address, or visit:

www.frontline-books.com

Foreword

T his biography honours one of Germanys extraordinary personages, as those who knew him maintained. He fought in the retreat battles of 1918 in the Potsdam First Guard Regiment on Foot, refused to join a saber-fighting student fraternity and trained as a boxer instead, studied and administered forestry for noble landowners in East Prussia and in the Prussian and Reich governments, served in the Polish and Russian campaigns in 1939 and 1941, eventually in 1942 became plenipotentiary manager and president of the estate of the former Royal House of Prussia (Hohenzollernsche Verwaltung). He was among the conspirators who met at Carl-Hans Count Hardenbergs Neuhardenberg estate and belonged to the circle that included Axel Baron von dem Bussche, Fritz-Dietlof Count von der Schulenburg and Claus Schenk Count von Stauffenberg, and he participated in the preparation of an assassination attack upon Hitler and the planning of the coup dtat. When investigations finally led to his arrest on 3 March 1945 and he was threatened with torture if he refused to name other conspirators, he knocked down his interrogator on 10 March with a right hook and threw himself out of a fourth floor window to his instant death. Eberhardt Schmidts biography is a captivating account of Plettenbergs life and of this extraordinary personage.

He was not alone, of course, as a list of anti-Hitler conspirators demonstrates, all of whom risked and hundreds of whom gave their lives to bring down the monster. But though they were many, they were not numerous enough to halt the orgies of murder and destruction. It was not they, and it was not the other rational and reasonable citizens who set the course of events at crucial junctures, but narrow coteries of inner circles. These were not answerable to public and transparent authorities and bodies, such as elected peoples representatives, or even judges in a state court (Staatsgerichtshof).

In Germany the Emperor William II in July 1914 decided with his war minister, his army chief of staff, the head of his military cabinet, his adjutant general, a captain of the naval staff, an admiral of the naval secretariat of state, the chancellor and the foreign secretary whether or not to promise Austria-Hungary support in case Russia intervened against her over Serbia. It was thus, too, in the Russian Empire, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and in the Republic of France. Each of the three emperors and the French president could have said no; if only one of them had said no, if France had warned Russia that it would not support Russian military intervention in the Balkans, there would have been very little likelihood of war. Even in the United Kingdom the King could have said no, while the House of Commons did not get to vote on war or peace until the Kingdom was in the war. Even in the British parliamentary monarchy, decent and rational people who were not ministers had practically no influence. An exception might have been the editor of a national newspaper. But large parts of the involved nations and their elected representatives were already in military confrontation mode. Where parliamentary votes were taken, they supported the war. In Germany, too, on 4 August 1914, even the socialists, including their radical Left, voted for the war appropriations.

Instead of having the opportunity to opt for diplomacy and negotiation, the nations, apart from the inner coteries, had no say. Given their gender, age and fitness they were obliged to serve and kill the designated enemiespeople like themselves. In sum, peoples lives were not their own, peoples lives were managed for them to the utmost extent. After the war, they were left alone to deal with the consequences.

In January 1933, again, a decision for war was taken by persons unanswerable to any scrutiny by parliamentary or other representative or supervisory authorities. Again, a person in authority, this time the president of the German Republic, Paul von Hindenburg, could have said no, and very likely there would not have been a Second World War. As it happened, a former chancellor, the state secretary in the Office of the Reich President, a banker and the presidents son Oskar von Hindenburg conspired to smuggle Adolf Hitler into the chancellorship. Hindenburg wanted an end to political turmoil and no more elections. Hitlers lie that he could form a cabinet based on majority support in parliament (Reichstag) convinced the President. Hindenburg enabled Hitler to establish a dictatorship, in the interest of safeguarding the German nation. But Hitlers appointment meant war, as he had been indicating in public speeches and as he himself declared to the Reichswehr leadership four days after his appointment.

Again, the powers that be were going to force eligible men into military service and combat against enemies who had not attacked Germany.

For people whose values were justice, peace and non-violence, it was impossible to do right, unless they fled their country. Failing that, Hitler was able not only to unleash another murderous war, but also to force soldiers into complicity in the most horrible crimes in recent human history. Kurt Baron von Plettenberg confronted the evil and gave his life as a result.

Peter Hoffmann

McGill University, Montreal

The Chancellor, Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg; the Foreign Ministrys State Secretary, Arthur Zimmermann; the Minister of War, Erich von Falkenhayn; the head of the Emperors Military Cabinet, Moriz von Lyncker; the Emperors Adjutant-General, Hans von Plessen; Captain Hans Zenker of the Naval Staff; Admiral Eduard von Capelle of the Naval State Secretariat.

Preface

Next page