Copyright 2016 by Danny Orbach

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to or to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, New York 10016.

www.hmhco.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Orbach, Danny, author.

Title: The plots against Hitler / Danny Orbach

Description: Boston : Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016 | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015043037 (print) | LCCN 2015046580 (ebook) | ISBN 9780544714434 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780544715226 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Hitler, Adolf, 18891945Assassination attempts. | Heads of stateGermanyBiography. | GermanyPolitics and government19331945. | Anti-Nazi movementGermanyHistory20th century. | Opposition (Political science)GermanyHistory20th century. | AssassinsGermanyHistory20th century.

Classification: LCC DD 247. H 5 072 2016 (print) | LCC DD 247. H 5 (ebook) | DDC 940.53/43dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015043037

Cover design by Brian Moore

Cover photograph Getty Images

v1.0916

Guilt, from Moabit Sonnets by Albrecht Haushofer, translated by M. D. Herter Norton. Copyright 1978 by W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. Used by permission of W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

This book is dedicated to my dear teacher Itzik Meron (Mitrani),

who accompanied this project from the outset

but did not have an opportunity to witness its publication.

Note on Ranks

Many of the protagonists in this book were officers in Third Reich military organizations: Wehrmacht, Navy, and SS. A number of them advanced in rank between 1938 and 1944the years covered hereand often more than once. Many books on the German resistance, especially in English, mention consistently the last and highest rank each individual obtained. Claus von Stauffenberg, for example, usually appears as a colonel, though he received this rank only in July 1944. In this book I mention the relevant rank for each time period. So, Henning von Tresckow is referred to as a colonel in chapters dealing with his assassination attempts in March 1943, but as a major general in later chapters. Two of the ranks of general officers in the Wehrmacht, general of infantry/artillery ext. and colonel-general, do not have a clear equivalent in English-speaking armies. Therefore, for simplicitys sake, I translate both to general. The SS had its own special ranks, which I convert to American military equivalents; for instance, Brigadier General Nebe instead of Oberfhrer Nebe.

Introduction

And when the cries of misery have reached my ear

I warned, indeed, not hard enough and clear!

Today I know why I stand guilty here.

ALBRECHT HAUSHOFER , 1945

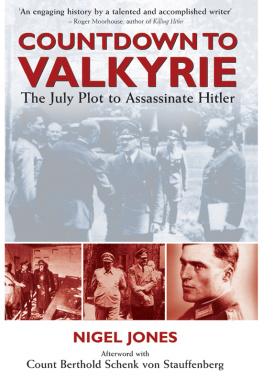

G UILT. NO OTHER word carries so much significance when considering German history. Even the drama of the July 1944 plot to kill Hitler, staged by Col. Claus von Stauffenberg and his confederates in the anti-Nazi resistance movement, is fraught with guilt and a maelstrom of other emotions, which we view through the thick fog of myth and memory.

The story of the anti-Nazi underground in the German army and its various attempts to assassinate Hitler has been cast and recast in books, movies, screenplays, and TV shows. That is hardly surprising, as the story contains elements of a thriller: nocturnal meetings in frozen fields; the elaborate drama of military conspiracies; bombs hidden in briefcases and liqueur bottles; and the dramatic day of July 20, 1944, with its abortive assassination and final, desperate attempt at a coup dtat.

Drama apart, the story of the German resistance has a crucial moral component. After all, the Nazi era is still viewed around the world, and most of all in Germany itself, through the lens of collective guilt, historical responsibility, and the burden of National Socialist crimes. Traditionalist German historians, from the 1950s to today, have tended to They were patriotic Germans, for sure, who hoped to save their fatherland from destruction, but nationalism was always secondary to morality.

Come the boisterous sixties, and the political climate in Germany changed dramatically. Young historians, like other educated Germans of their age, began to mercilessly examine the myths of the past. The German resistance did not survive the new critical climate unscathed. From the late sixties on, critical, left-leaning historians such as Hans Mommsen, Christoph Dipper, and Christian Gerlach cast doubts on the integrity of the German resistance. To them, the conspirators, most of whom were conservative bureaucrats and military officers, were dubious figures to begin with. True, Count Stauffenberg tried to assassinate Hitler and paid for it with his life. But had he not cooperated with the Nazi regime for many years beforehand? What about the other conspirators? Were they really moral men and women, anti-Nazis to the core, who tried to stage a revolt of conscience, or rather were they opportunistic figures who cooperated with the Nazis until the war was no longer winnable?

Gradually, laurel after laurel was removed from the heads of previously revered conspirators. They may have slowly learned to hate the Nazi regime and opposed most of its crimes, argued Hans Mommsen, but they were also antidemocratic reactionaries.

The debate goes on. The German resistance to Hitler, it seems, is a field in which historical arguments are not purely academic but shot through with passion. People are elevated to Olympus by one scholar, only to be condemned to the darkest hell by another. Professional and even personal accusations are hurled back and forth. I myself, as the following pages will demonstrate, am far from a neutral spectator. In the first days of my interest in the resistance, as a young student in Israel, I was impressed by what I saw as the selfless bravery of the German conspirators. As a third-generation child of Holocaust survivors, I was deeply moved to read about the conspirators sympathy for the persecuted Jews. I was equally disappointed to discover their supposed anti-Semitism and complicity in war crimes in Dippers and Gerlachs accounts. I decided to delve into the sources and form my own opinion.

In ten years of research prior to the publication of Valkyrie, my Hebrew-language monograph on the resistance, I examined every primary and secondary source I could find.

However, I could not return to the cozy, heroic picture presented by many traditionalist historians. True, some of the critical historians were sloppy, but the questions they asked were worthwhile. Gradually, I came to believe that one must transcend the current moralistic debate, redraw its terms, and reframe it altogether.

This book is an attempt to do that. It retells the story of the resistance, shedding new light on its psychological, social, and military dynamics, as well as on the reasons behind its decision to assassinate Hitler. I use the German resistance as a test case to draw specific insights with general implications: Why are certain people, and not others, drawn to active resistance despite the mortal risks involved? Who is most likely to become a resistance fighter? What can we learn about the complex and fluid motives that may lead people to resist? When one steps out of the moralistic debate, even without disavowing it entirely, a whole new world of meaning may be discovered. In it, motivations and intentions are more properly seen as slippery and difficult to pin down. As the medievalist Aviad Kleinberg wrote in his study of Catholic saints,

The question of what really motivates the ascetic is meaningless, as is the question of whether a true saint really exists. If true means perfectly pure, the response will always be negative. Nothing in the world is pure. Does this mean that everything in the world is completely impure? There again the response will be negative. In this world we are always dealing with relative values... Furthermore, what makes a person act at one moment is not necessarily what makes him act at another. People sometimes do things without intending to do them; sometimes honor, power, habit, or fatigue can alter the purest intentions. People rarely conform to clear and precise models, just as they rarely have feet that perfectly fit size 11 shoes. They fit, more or less. They fluctuate and shift from one model to another. At any given moment their actions reflect the balance of drives and contingencies that result from a unique situation which cannot be reproduced.

Next page