CONTENTS

Guide

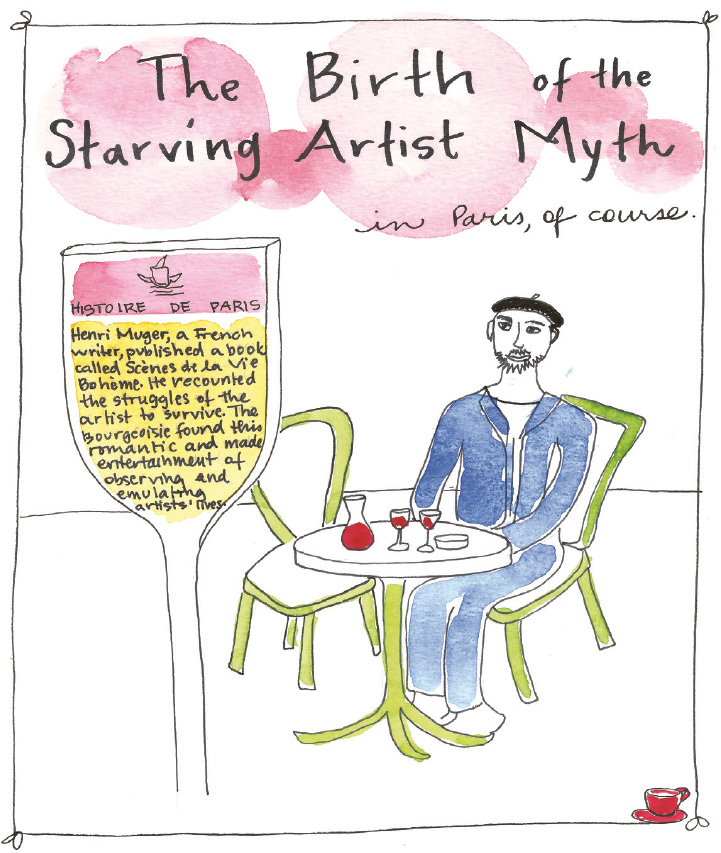

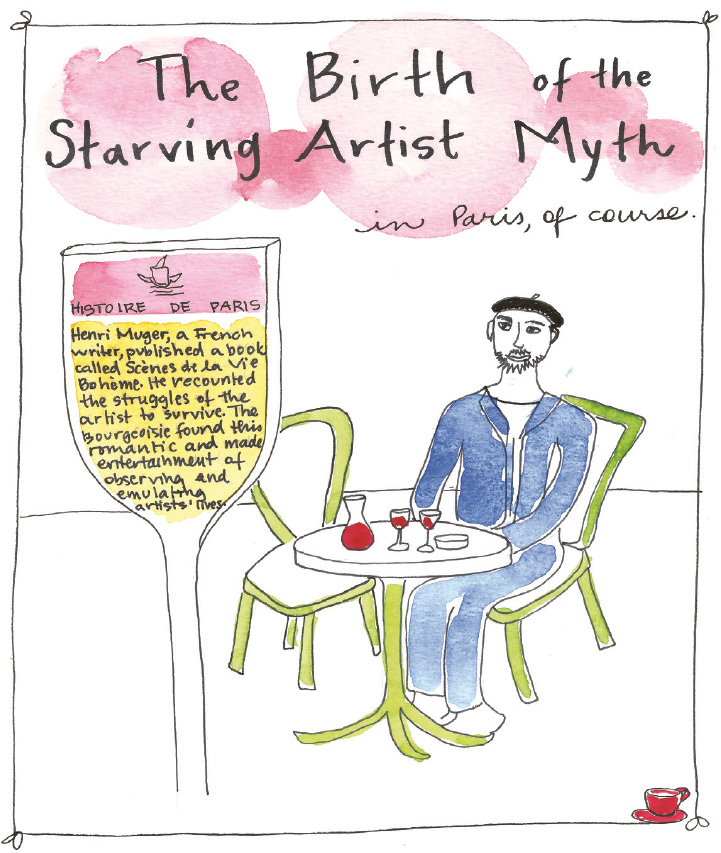

I n January 1861, Henri Murger lay coughing out the last of his life. In his short thirty-nine years, he had managed to become an influential writer, but had lost all of his wealth. A friend sent money to help pay his medical expenses, but it wasnt enough and Murger was near deaths door.

One can imagine Murger reflecting back on his life and the way that he had managed to popularize Bohemian culture. His popular book Scnes de la vie de bohme told the story of the Bohemians in such a way that he made their poor lifestyle seem somehow better than the lives of the nobles in Paris. The Bohemians in Murgers book were prototypes of the starving artistwriters, painters, and other creatives who eschewed material wealth in favor of creating art without commerce.

Murgers book, originally a collection of short stories, inspired Theodore Barriere to write a play with Murger called La Vie de la Bohme, which played to great success at the Thtre des Varits. This play later inspired Puccinis classic opera La Bohme, which in turn inspired many other works, including the megahit musical Rent (both stage and film adaptations).

The Bohemians were not the only group to pursue literary and artistic endeavors while living in financially poor circumstances. Subcultures similar to the Bohemians exist in written record as far back as Alexandria and Rome.

These subcultures were rarely celebrated. They were seen as dirty, second-class citizens by the mainstream and even viewed themselves that way. The sons and daughters of peasants, they moved into the cities to obtain work, but were confronted by the cold reality that there were not enough jobs for them. These Bohemians were starving artists not so much out of a desire to rebel against the culture but rather because Frances economy had not yet expanded enough to give them good jobs, or any jobs.

Murger was one of these people. He was the son of tailor. He toiled at odd jobs but didnt have the talent to be an artist, so he turned to writing. In his writing, he romanticized the life he and his friends lived. It was the advent of Murgers Scnes that raised the Bohemians from their place of cultural obscurity to an icon of cultural relevance and aspiration.

When Scnes became popular, people flocked from all around Paris to visit the Bohemian parts of the city. They took over the cafes, wandered through the streets gawking like they were at a zoo, and even went so far as to create fashions after the Bohemian lookironically born more of necessity than a desire to look great or make a statement.

But Murger had expressed that this Bohemian life was a means to an end, a temporary way to live while figuring out how to bring in more money. People who were unable to lift themselves out of this life of poverty would destroy themselves. This is exactly what happened to Murger. His final words were, No more music! No more alarums! No more Bohemia!

If Murger himself, an early teller of the stories of the starving artist, wished that people understood this was not a lifestyle to emulate, then why has modern culture so thoroughly embraced it?

The answer comes with the understanding of how myths are made.

Some ideas become so prevalent, so popular, that they take on a life of their own. They start out as a simple story, told by a good storyteller, and grow. With each telling, the less interesting parts are taken out, while the more interesting, salacious, and compelling parts are embellished. As more and more people tell the story, people start to believe the story is true.

The Bohemian story is a myth, one people rely on to explain the artist mindset. The Bohemians were untrained artists who were not compensated for their art. In Murgers telling, these artists were better than mere mortals. They were like Greek heroes: In ancient Greece, to go no further back in the genealogy, there existed a celebrated Bohemian, who lived from hand to mouth round the fertile country of Ionia, eating the bread of charity, and halting in the evening to tune beside some hospitable hearth the harmonious lyre that had sung the loves of Helen the fall of Troy.

Not only does Murger transform the Bohemian from an ethnic group to a class of artists, but he transforms these artists into a class that includes Raphael, Michelangelo, Molire, and Shakespeare, and makes them equal to the kings of France, the saints of Catholicism, and gods. He sets up the reader to believe that Bohemia, the state of being a young, poor artist, is a desirable and noble state of being while also admitting that Bohemia is, and should be, a temporary state: Bohemia is a stage in artistic life; it is the preface of the Academy, the Hotel Dieu, or the Morgue. In other words, its okay to be a poor, struggling artist. Enjoy that time, but move on and become a professional, or face the reality of poverty: sickness and death.

Despite Murgers warnings, many artists throughout history have embraced the starving artist mindset, choosing to suffer for their art. Society has a habit of rewarding the greatest of these artists postmortem.

Mozart was a successful composer during his life. The popular legend is that the rival composer, Salieri, helped keep Mozart down by interfering in his life and preventing him from achieving key positions. While it is certainly true that Mozart and Salieri competed for several of the same positions and opportunities, there is no evidence that Salieri used his influence to harm Mozart. The two even created a handful of works together.

What is true is that some of Mozarts choices contributed to his poverty. Early in his career, he left a permanent position as a court composer in Salzburg in search of something he would enjoy more. Over the course of the next few years, Mozart turned down several well-paid opportunities. After receiving a position with Bishop Colloredo in Vienna, Mozart made his presence so painful that the bishops steward dismissed him with a literal boot to the arse. Even after his freelance career began to take off, Mozart hamstrung his fledgling family by spending more than he was bringing in. His lavish lifestyle included a large apartment in Vienna, the most expensive instruments, and high-end private schools for his son.

None of this is to condemn Mozart; rather, it shows that while popular myth says that artists are by their nature poor, it is certainly true that a hardworking, talented artist can make a living with their artif they are smart about how they do it. Mozart took risks, made enemies, and made poor financial decisions. I have little doubt that if Mozart had been a little more conservative with his money, he would have lived longer and created even more great work.

Vincent van Gogh was an exceptionally talented painter, even as a young artist, to the point that the art dealer Goupil & Cie hired him as a twenty-year-old, paid him a handsome salary, and put him up in a flat in London and then Paris. Van Gogh, however, didnt like the commercial side of art and let collectors know it, causing his dismissal after just a few years.

After his dismissal by Goupil & Cie, Van Gogh chose to live a life of poverty as a minister to a small mining village. Signs of his mental illness began to manifest. He failed the ministry exam, moved in with a prostitute, burned his hand in a fit of protest over his love not being reciprocated, was accused of rape, and famously cut off his own ear. He was remembered as dirty, badly dressed and disagreeable, and very ugly, ungracious, impolite, sick by Jeanne Calment, a girl who sold him colored pencils.