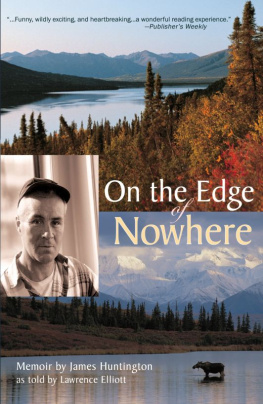

On the Edge

of Nowhere

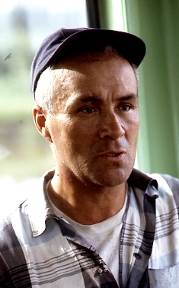

by James Huntington as told toLawrence Elliott

Foreword by Gregory FrankCook

SMASHWORDS EDITION

Published by

Epicenter Press, Inc.

EPICENTER PRESS

Alaska BookAdventures

Epicenter Press is a regional pressfounded in Alaska whose interests include but are not limited tothe arts, history, nature, and diverse cultures and lifestyles ofAlaska and the Pacific Northwest.

Text copyright 2002 Jimmy HuntingtonFoundation and Lawrence Elliott Cover photographs copyright 2002Alaska Stock Images Third Edition published by Epicenter Press,2002 Second Edition published by Press North America, 1991 FirstEdition published by Crown Publishers, 1966

Photographs by LawrenceElliott

Digital conversion by Lava E-booksInc.

All rights reserved. This e-book islicensed for your personal enjoyment only. This book may not bere-sold or given away to other people. If you would like to sharethis book with another person, please purchase an additional copyfor each person you share it with. If you're reading this book anddid not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only,then you should return it to Smashwords.com and purchase your owncopy. Thank you for respecting the author's work.

ISBN: 978-1-935347-29-3(eBook)

PRODUCED IN THE UNITED STATES OFAMERICA

Foreword

J immyHuntington used to say, Where theres life thereshope.

It was his maxim for survival inthe wilderness, as when he fell through the ice on a sub-zero dayand had about five minutes to get a fire going with wet wood andnumb fingers before he froze to death. It was also his philosophyof life, and he said it so often that it became a joke between us,as when he pointed out a pretty girl across the street with an oldmans shaking hand and we both spoke together: Where theres lifetheres hope.

We met when Jimmy was on theFisheries Board, the toughest job in Alaska, and I was executivedirector. It fell on the shoulders of the seven Board members tomake the regulations for the conservation and management of all thefisheries resources in this immense statecommercial fishing, amulti-million dollar industry; subsistence fishing, the life bloodof the Native villages; sport fishing, a pillar of tourism,Alaskas third biggest moneymakerand that was the easy part. Tocut up this pie, to decide who gets what, to take a stand in thefierce competition between this region and that, between seiners,gill netters, trollers, crabbersthat was the hard part.

The Board met between 50 and 80exhausting 12-hour days a year, taking public and scientifictestimony all over the state, deliberating and voting. Almostwithout exception, Jimmy came down on the side of the little guy.And at the end of each day, he and I, sharing a room in some hotelor boarding house, would walk home in the cold night rehashing thetestimony and the decisions and, if we were lucky, find a placewhere Jimmy could warm up with a banana split.

Somewhere along the line, headopted me, although I wasnt sure I deserved it. But along withthe honor came invitations to go hunting and trapping with him, andlet me tell you, that beat the daylights out of Alaska FisheriesBoard meetings.

At that timeit was in the early1980sJimmy lived in a small log cabin downriver from the villageof Huslia on the south bank of the Koyukuk. It was decorated to histaste: on the wall hung a fan made from the tail feathers of aspruce grouse, and a white ermine skin; a faded panel of woodnailed up near the door said, Carnation Milk From Contented Cows.The landscaping consisted of a stand of short spruce and birchtrees typical of the latitude. But they were tall enough to hide abear so you never went far from the cabin without arifle.

One September I came flying up toHuslia to join Jimmy on a moose hunting trip, excited as a kid withhis first rifle. We traveled in Jims river boat, running for dayson end through the endless untouched forests of interior Alaska. Mymost cherished memories of those crisp cold days along the Koyukukand Yukon are of Jimmy calling over his shoulder, Grab the grubboxtime for tea. We would beach the boat and I would gather woodwhile Jim made fire and roasted moose ribs, and we ate and talkedand enjoyed the feeble heat of the midday sun less than 50 milessouth of the Arctic Circle. One night a foolish black bear tried torob our cache of moose meat and wound up hanging on the drying rackbeside the moose.

Another year we spent a monthtrapping beaver at the base of the south slope of the Brooks Range.We were in the woods through all of a bitterly cold February,sharing a small canvas tent, sleeping on top of spruce boughs andusing birch bark to start the morning fire. In my minds eye Istill see the Jimmy Huntington of that magic time, moving ahead onhis snowshoes, ax in hand, utterly at home in the wilderness, happyas a man can be.

Anyone who knows me knows that myteenage daughter Slim is the light of my life. And one of my devoutwishes for her is that sometime in her life she comes to know assolid and singular a human being as Jimmy Huntington.

Gregory Frank Cook

Chapter One

My Mother

M Y MOTHERWAS ATHABASCAN, born around 1875 in a little village at the mouthof the Hogatza River, a long days walk north of the Arctic Circle.The country was wild enoughblizzards and sixty-below cold all thewinter months, and floods when the ice tore loose in spring,swamping the tundra with spongy muskegs so that a man might traveldown the rivers, but could never make a summer portage of more thana mile or so between them.

And the people matched the land.From the earliest time in Alaska, there had been bad feelingbetween Indian and Eskimo, and here the two lived close together,forever stirring each other to anger and violence. If an Indianlost his bearings and tracked the caribou past the divide thatseparated the two hunting grounds, his people would soon bepreparing a potlatch to his memory, for he was almost sure to beshot or ground-sluiced, and his broken body left for the buzzards.Naturally this worked both ways. Then, in the 1890s, prospectorsfound gold to the west, on the Seward Peninsula, and the white mancame tearing through. Mostly he was mean as a wounded grizzly. Henever thought twice about cheating or stealing from the Nativepeople, or even killing a whole family if he needed their dogteamanything to get to Nome and the gold on thosebeaches.

And once, through two winters and asummer, my mother, who looked like a child and weighed less thanninety pounds, walked a thousand miles across this desperate landto get back to her home and her two children.

Her name was Anna, and her fatherwas a Native trader. All year he traded among his own people. Then,with the first long days of March, he would make his way down theHogatza to the head of the Dakili River, the divide between theEskimo and the Indian lands, and there he would meet Schilikuk, theEskimo trader. This was permitted because each needed things thatonly the other had, and it was the only known peaceful contactbetween the two races.

As soon as Anna was old enough, shebegan to accompany her father on these trips, and so she learnedthe Eskimo language. They would load up the sled with their goodsand set off toward the Dakili, a five-day trek for a good strongdog team, and make camp on the south slope of the boundary hills.This was as far as it was safe to go. On the other side, Schilikukthe Eskimo would be making his way south along the Selawik River,and the great trading ritual was about to begin. In all the yearsthat Anna went with her father, it never changed.

Next page