My foray into the realm of alternative dwellings moved from abstract daydreams to reality in August of 2011. I left my fifth-floor walk-up apartment in Manhattan at five in the morning carrying my last possessionstwo duffel bags, a surfboard bag, and a large Osprey backpackand headed to LaGuardia Airport to catch a flight to Reno, Nevada, where I picked up a 1987 VW Vanagon Syncro. Over the next three years, I logged 150,000 miles driving around Mexico, Canada, and the western United Statesliving first in the Vanagon and then in a Toyota pickupbased camper. I parked at night on public land, in friends driveways, and on city streets. I used bathrooms in coffee shops, restaurants, and truck stops. My vehicle was my bedroom and the outdoors was my living room. This period in my mid-twenties completely changed my expectations regarding what I needed to live comfortably, and what compromises I needed to make in order to be happy. It helped satisfy my thirst for excitement and confirmed my strong belief that there is more to life than a corporate nine-to-five.

Along the road I met people living in all sorts of different ways: in tents packed on the back of their motorcycles; in rustic cabins at 10,000 feet in the Colorado Rockies; in Airstreams in the hills above Los Angeles; and in treehouse colonies overlooking fields of marijuana in southern Oregon. The thread that tied it all together was that they allsome by choice and some by circumstancelived in small homes they either built or actively maintained themselves, with self-taught know-how and their own hands. None of these houses had three bedrooms, two baths, and a garage. They were way below the average size, and most were less than 1,000 square feet.

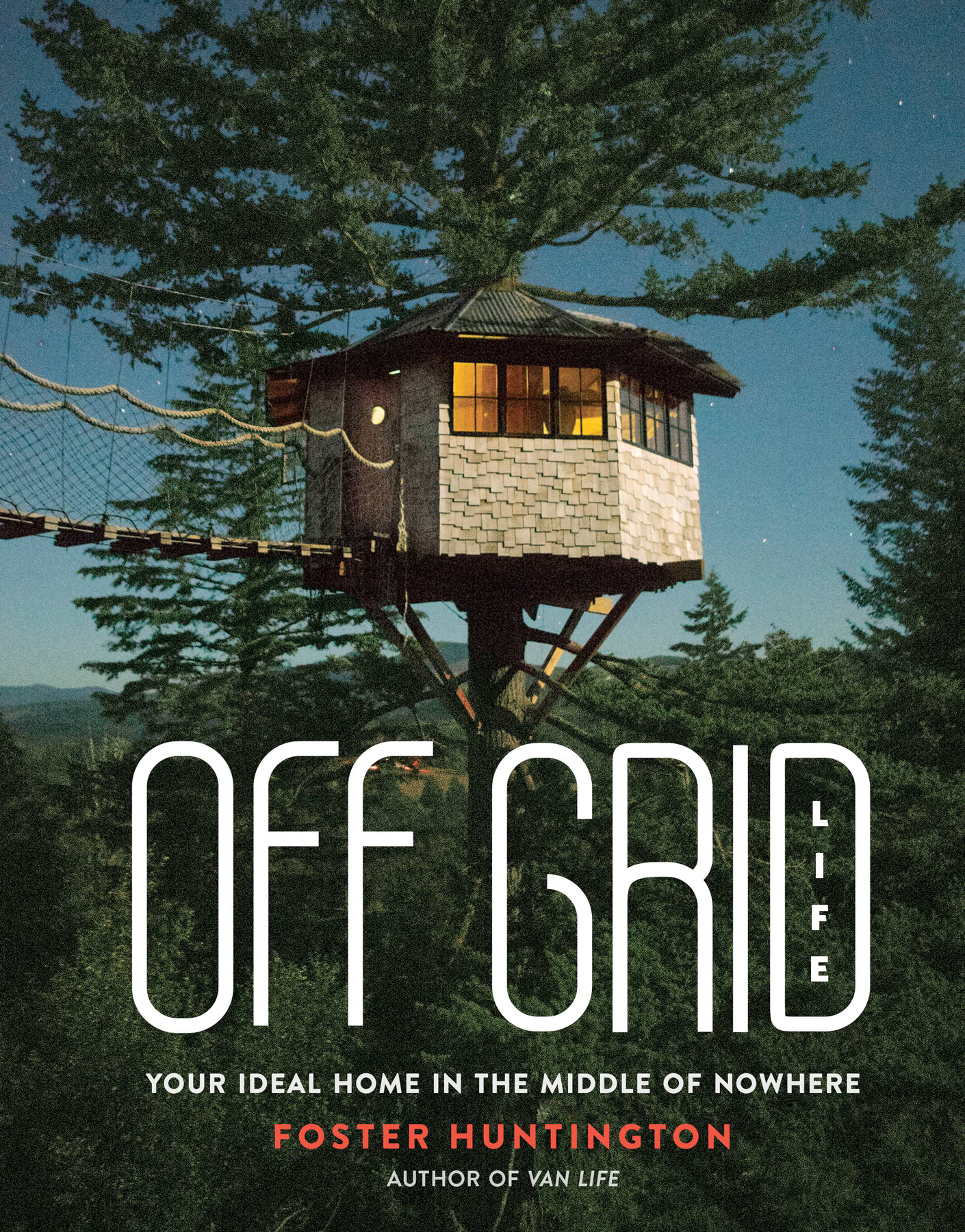

After three years of living out of my vehicle full-time, I started pondering my next home. I looked at houses in Portland, Oregon, but quickly realized I had no reason to live in a city beyond the convenience of coffee shops, restaurants, and grocery stores. My ideal home wasnt surrounded by neighbors in a city dead set on matching the gentrification of the Bay Area and Brooklyn. I wanted a place with the infrastructure to allow me to undertake larger projectsbuilding, photography, filmmaking, etc.and enough space to host all the friends that had been so accommodating to me on my travels. I wanted chickens, goats, and a garden. I wanted to have bonfires and cook over coals. I wanted to be able to pee outside without risking locking eyes with a neighbor midstream. I didnt want to take on a mortgage that would force me to work jobs I didnt want to work. I decided to look in rural areas, places a little more off the beaten path. I started brainstorming with my longtime friend, Tucker Gorman (featured in this book in both the Treehouses and Tiny Homes chapters), and we hatched a plan to build a series of treehouses and bridges in a cluster of Douglas fir trees on the top of a small dormant volcano overlooking the Columbia River Gorge.

We built the treehousesan adventure described in more detail in the chapter on treehousesand I lived in them from 2014 to 2019. They didnt have running water or bathrooms, but since Id been living in my car, it was a relatively easy transition. Using the treehouses as my bedroom and office, I lived, year round, 20 feet off the ground in a 200-square-foot space. I learned to tell what the weather was doing by the sounds the treehouses and bridges made. I dreaded the annual ice storms that coat my beloved Douglas fir trees in inches of ice. I refused to retreat to the ground during these stormy nights. I weathered falling tree limbs, shattering ice, and rocking trees with the same stubbornness as Ahab chasing the white whale. I noted the end of winter with the arrival of the tree swallows in April. Flying around the treehouses and below the bridges, chasing bugs and nesting in the trees, their coming always reminded me that we shared the same trees as our home.

As my mid-twenties moved on into my early thirties, my living needs changed again. My girlfriend, Kaycee, moved in with me, and we got a cocker spaniel puppy, Gemma. The treehouse started showing its limitations. Kaycee did not seem to enjoy peeing off the edge of the deck in the middle of the night the same way I did. There is a 1,000-square-foot converted barn home up at the Cinder Conethe nickname of my property up in the Columbia River Gorgeabout 200 feet from my treehouses. We started spending more nights on the ground and fewer in the trees.

These new presences in my life contributed to my evolving understanding of living spaces. When we travel in my van, Gemma actively seeks out the small storage cubby under the bed. She prefers to sleep there rather than on the mattress with the down comforter and pillows. When we are up at the Cinder Cone, Kaycee often chooses to sleep in a small loft or in the van instead of the queen-sized bed in our large bedroom. I see a pattern in their choices. Small spaces offer a sense of security and coziness that is very comforting. Over the course of human and mammal development, weve only been living in large, one-family houses for a very short time, about two hundred years.