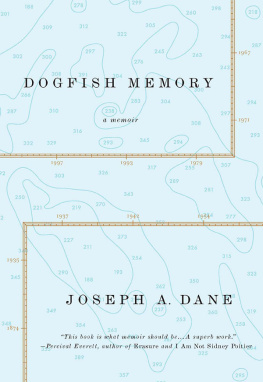

DOGFISH MEMORY

SAILING IN SEARCH OF OLD MAINE

JOSEPH DANE

THE COUNTRYMAN PRESS

WOODSTOCK, VERMONT

Copyright 2011 by Joseph A. Dane

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systems without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages.

Design and composition by S. E. Livingston

Dogfish Memory

ISBN: 978-1-5815-7885-0

Published by The Countryman Press,

P.O. Box 748, Woodstock, VT 05091

Distributed by W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.,

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

Fr Elise

CONTENTS

PREFACE

Change. Change is bad.

Linda Jane, mocking me

I have a lot of hippie friends, although now there are different names for them. They cut and split their firewood to heat the houses they have built themselves. They grow their own vegetables and on a good year theyll still be eating them in spring. Most grew up elsewhere. They range in age from twenty to eighty-five. All of us play Maine in our own ways, although I grow nothing more complex than rhubarb and I cannot operate a chain saw. I do what my father did, and sometimes I think he must have followed what he thought his brother and his father did. But when I read their letters from the 1930s, I think I dont know these men at all.

I dont hunt because Ive never been very good at it. Waiting dutifully and motionless in now-illegal hunting stands near Brownville Junction, I sensed nothing but the growing November cold. This cannot be Maine for real. I did not inherit the patience of my father, who never hunted, but whose neuroses suddenly vanished as the sights aligned in his calmed hands.

I dont fish because each amateurish cast reminds me how much less dedicated I am than my immigrant grandfather, who came from Sweden and fished those western streams into the sterility you find them in today. My uncle settles a fly twenty yards away on the concentric circles of a rise. My line splashes erratically over the surface.

I dont hike much because hiking is a slow and tedious thing and too many graduates of too many Outdoor Leadership Schools and Outward Bound programs lecture me on wool and proper socks and underwear and brook no deviations from their fire-building and bum-wiping ideologies. On the day I first met Linda Jane, I hiked bored and alone to the nearest high ridge with a name on the topographical map. I took off my boots and continued barefoot and naked, the hammers of the menfolk now silenced by the deep Maine woods, the ridge dry, like the hills of the San Gabriels in California. Sailing, even in the coldest June, I strip down in the night air and walk as deftly as I can around the deck.

I dont ski or sled or strap on snowshoes because I am now a seasonal resident of Maine and I rarely see the snow except on the mountains surrounding Los Angeles. When I was last here for the winter, I taught myself to figure skate on the contrived ice of hockey rinks in southern Maine, and I may as well have been in Rochester, Tulsa, or Ontario.

I play Maine with boats, while others cut wood, and others grow vegetables and study the readings of thermometers in compost heaps, and others kill things, and others march deep into the winter woods. They speak the language of these things, and form their phrases carefully, in ways that wont embarrass them or earn a reprimand from a teacher, lover, or an editor. As I warm myself in the hunting shack in Brownville Junction, the old Maine hunter enters with his rifle held at the hips; it is aimed directly at the chest of a friend beside me, his name made famous by his familys shoe company. That thing loaded? he asks. And this authentic Maine man, now in his midfifties, answers: Safetys on. Safetys on.

This is a book about sailing, and I could thus just begin with some grand metaphor about leaving a dock or harbor or an anchorage, or perhaps detail the origins of my history with sailing. I could discuss the lives of my ancestorsmy grandfather, father, and my uncle Duke, who sailed with Byrd to Antarctica and talked of nothing but his glory days playing football for Exeter. But sailing, as I have experienced it, has never lent itself to such histories. And to discuss it in this fashion is to fall victim to the language of sailing magazines and the dangerous nostalgia of traditional cruising guides. Instead I think: I sail alone; I sail with others; and I sail with Linda Jane.

She is on the tiller, the curve of her cheek like the curve of the hull itself. The boat is heeled over. I think, watching Linda Jane, how the feel of the boat moving so quickly through the water on a late May afternoon was once terrifying to me. But terror is the wrong word for this. There is no word for this in the old sailors perfect lexicon. She purses her lips in oblivion as the bow cuts its daysail course toward Hope Island, southwest of Chebeague.

CHAPTER ONE

PORTSMOUTH

Yet another incomparably beautiful anchorage.

Gnomic utterance recorded 1993

The first port on the southern coast of Maine is Kittery; it faces Portsmouth across the Piscataqua River, which divides Maine from New Hampshire. Years ago I lived a year of married life in New Hampshire, a river-band away from Maine. Here, I came close to forgetting Maine as I learned to cook, and kept house, and walked down to the river every evening to do some fly-fishing in unconscious imitation of that branch of my family now in Colorado. If this were a coming-of-age story or romance, my life in Portsmouth would be the end point, the bourgeois life for which all my adolescence served as prelude. But it is rather the beginning. I planned to leave Linda Jane in Portsmouth, with her horses and cuckoldings, and leave with her the coast of Maine as well. I would go south, to New Orleans, the most foreign place I would ever know. This is the kind of thing young people do. I would become, I thought, something of a novelist, although I didnt know the novels I would write, and I had no idea what lives such people as novelists led, nor what they did to gain access to such lives. I simply skimmed their paragraphs and imagined I could do better.

Preparing for this future, about which I knew nothing, I drove not south at all but east, Down East as it turned out, to collect and read my notes and type my drafts and contemplate grand schemes of things with my now-dead friend James.

James came back from Vietnam as he had left for Vietnam, directionless, obtuse, and finally grotesquely fat. He stayed in a family cottage in Cutler, which is nearly as far from the southern coast of Maine as you can get and still be on the coast of Maine. He used an outhouse, a badly tended one, and hand-pumped water from the well to the kitchen. As I typed my drafts, he lay in bed, smoking marijuana he had brought back from Vietnam (he claimed), and read and reread copies of letters he had written when he was overseas. Letter after letter. Day after day. He smoked. He imagined the actors who would play the parts of our fictions. He played chess, with unspeakable slowness, fifteen to twenty minutes for each pedestrian move. I read Camus and played bad losing moves in seconds. He died while running in a local road race for some charity organized in Machias, if Machias was ever a place for charity, back when both running road races and dying itself seemed extraordinary.

When I left Linda Jane, or planned to leave her, she took in a roommate to replace me. A heavy-limbed, small-waisted, well-hipped hippie girl, it seemed, rust hair and skin, and long fingernails she used to stroke you without so much as touching you with her fingertips. I took her roommate, this other Linda Jane, down to the Piscataqua in the evening. It was the last week I would spend in New Hampshire. We swam in the summer water in the shadow of the newly completed bridge.