Copyright 2014 by Suki Kim

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Crown Publishers, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House LLC, a Penguin Random House Company, New York.

www.crownpublishing.com

CROWN and the Crown colophon are registered trademarks of

Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Kim, Suki, 1970

Without you, there is no us : my time with the sons of North Koreas elite / Suki Kim.First edition.

pages cm

1. Kim, Suki, 1970 2. English teachersKorea (North)Biography. 3. Korea (North)Politics and government2011 4. Korea (North)Social conditions21st century. 5. Elite (Social sciences)Korea (North) 6. EducationGovernment policyKorea (North) I. Title.

PE64.K45A3 2014

818.603dc23

[B] 2014012730

ISBN 978-0-307-72065-8

eBook ISBN 978-0-307-72067-2

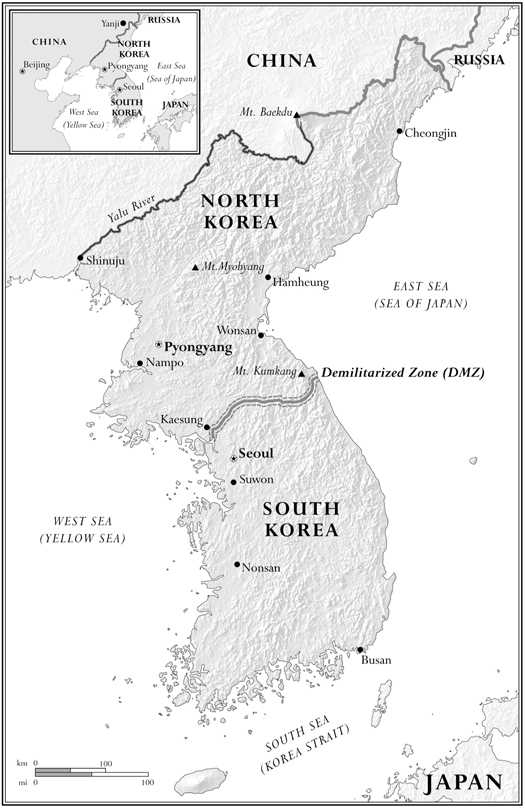

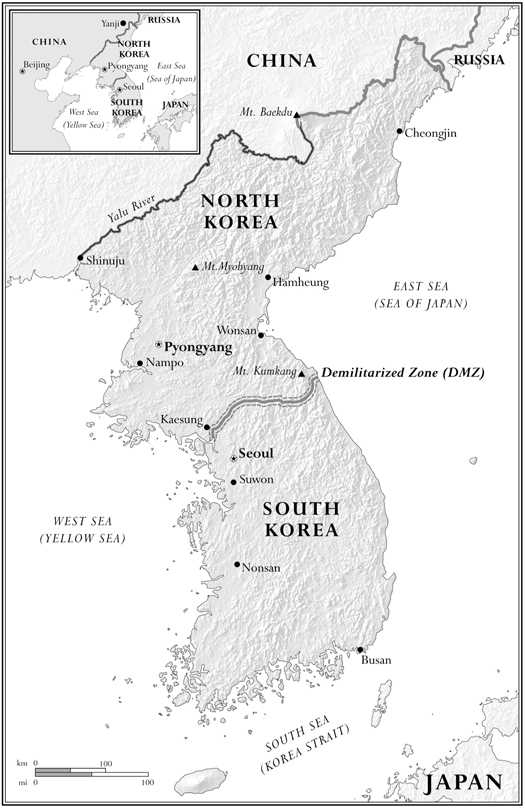

Map by Mapping Specialists

Jacket design by Na Kim

Photo on : Sunchon Airport, Pyongyang, 2002. The airport greeter holds a Sun of the 21st Century sign to commemorate Kim Jong-ils sixtieth birthday.

Photo on : Students at PUST taking their final exam in December 2011.

v3.1_r2

FOR MY MOTHER AND MY SISTER

Contents

Prologue

T IME THERE SEEMED TO PASS DIFFERENTLY. WHEN YOU ARE shut off from the world, every day is exactly the same as the one before. This sameness has a way of wearing down your soul until you become nothing but a breathing, toiling, consuming thing that awakes to the sun and sleeps at the dawning of the dark. The emptiness runs deep, deeper with each slowing day, and you become increasingly invisible and inconsequential. Thats how I felt at times, a tiny insect circling itself, only to continue, and continue. There, in that relentless vacuum, nothing moved. No news came in or out. No phone calls to or from anyone. No emails, no letters, no ideas not prescribed by the regime. Thirty missionaries disguised as teachers and 270 male North Korean students and me, the sole writer disguised as a missionary disguised as a teacher. Locked in that prison disguised as a campus in an empty Pyongyang suburb, heavily guarded around the clock, all we had was one another.

PART ONE

Anti-Atlantis

1

A T 12:45 P.M. ON MONDAY, DECEMBER 19, 2011, THERE WAS A knock at my door. My heart sank. I knew who would be there. I ignored it and continued shoving my clothes into the suitcase. The knock came again. She knew that I was inside, and she was not going to go away. Finally I stopped what I was doing and opened the door. There stood Martha, a lanky twenty-four-year-old British girl with glasses, with whom I had been sharing teaching duties. You must come to the meeting right now, she said. I sighed, feeling the weight of the past six months there among thirty Christian missionaries, now gathered in secret for the pre-Christmas prayer meeting. Then she whispered, Hes dead, pointing at the ceiling. I thought that she meant God, and I was momentarily confused. I have never read the Bible, and my family is largely atheist. Then she said, him, and I realized she meant the main God in this world: Kim Jong-il.

Was it fate that my North Korean experience began with his birthday and ended with his death? It was February 2002 when I first glimpsed the forbidden city of Pyongyang as part of a Korean-American delegation visiting for Kim Jong-ils sixtieth birthday celebrations. It was only a few months after 9/11, and George W. Bush had just christened that country part of an axis of evil, so it was an inauspicious time for a single American woman to cross its border with a group of strangers.

Over the next nine years, with each implausible crossing of its immutable border, I became further intoxicated by this unknown and unknowable place. This isolated nation existed under an entirely different system from the rest of the world, so different that when I arrived in 2011, I found myself in Juche Year 100. The Democratic Peoples Republic of Korea (DPRK) follows a different calendar system, which counts time from the birth of their original Great Leader, Kim Il-sung, who died in 1994; Juche, which roughly means self-reliance, is at the core of North Koreas foundational philosophy. Almost every book I ever saw there was written by or about the Great Leader. The state-run media, including the newspaper Rodong Sinmun and Chosun Central TV, reported almost exclusively on the Great Leader. Almost every film, every song, every monument heralded the miraculous achievements of the Great Leader, the role passed down through three generations, from Kim Il-sung and Kim Jong-il to Kim Jong-un, who was twenty-nine when he assumed power in 2012 and became the worlds youngest head of state. It has been reported that every home in the country is fitted with a speaker through which government propaganda can be broadcast, and that more than thirty-five thousand statues of the Great Leaders are scattered across the country.

But while the regime dabbles with nuclear weapons, provoking repeated United Nations sanctions, the people of North Korea suffer. The 1990s famine (known as the Arduous March) killed millions, as much as a tenth of the entire population, and even now the World Food Program reports that 80 percent of North Koreans experience food shortages and hunger. It is estimated that forced labor, executions, and concentration camps have claimed over a million lives since 1948. According to the latest UN report, the DPRK maintains some twenty gulags holding some 120,000 political prisoners (Human Rights Watch estimates 200,000). These numbers are inevitably approximate since nothing there is verifiable. Almost no North Koreans are allowed outdefectors risk executionand almost no foreigners are allowed in except those on packaged tours, most holding European passports, and they get to see only what is allowed. In this global age of information, where secrets have become an anachronism, North Korea stands apart.

My obsession with this troubling countrybecause it indeed became an obsessionwas based on more than just journalistic interest. The first time I entered North Korea, I was not sure what a delegate was and did not know much at all about the proKim Jong-il group I was traveling with. This makes me sound either extremely irreverent or extremely young, but I was neither. My ignorance was willful. Since getting a visa into the country was so difficult, I thought it was best not to appear too inquisitive. But there was something else, too: a part of me, a very insistent voice inside, did not want to know those details. For those of us who grew up in 1970s South Korea, anything to do with North Korea is accompanied by a certain foreboding. And for those of us whose family members were abducted into North Korea, this fear runs still deeper. If I had known as much as I do now, more than a decade later, I doubt I would have made that first, fateful trip. But I did get on a flight from JFK, on Korean Air, one of the worlds most modern and luxurious airlines, and then almost twenty hours later, via Seoul and then Beijing, boarded North Koreas state-owned Air Koryo, where the only reading material was a magazine about the Great Leader. And I would cross that same border into Pyongyang repeatedly for the next nine years.