Contents

Copyright 2012 John Wiley & Sons Singapore Pte. Ltd.

Published in 2012 by John Wiley & Sons Singapore Pte. Ltd., 1 Fusionopolis Walk, #07-01, Solaris South Tower, Singapore 138628.

The first edition was published in 2004.

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as expressly permitted by law, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate photocopy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center. Requests for permission should be addressed to the Publisher, John Wiley & Sons (Asia) Pte. Ltd., 1 Fusionopolis Walk, #07-01, Solaris South Tower, Singapore 138628, tel: 65-6643-8000, fax: 65-6643-8008, e-mail: .

This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold with the understanding that the Publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional person should be sought. Neither the author nor the Publisher is liable for any actions prompted or caused by the information presented in this book. Any views expressed herein are those of the author and do not represent the views of the organizations he works for.

Other Wiley Editorial Offices

John Wiley & Sons, 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, USA

John Wiley & Sons, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, P019 8SQ, United Kingdom

John Wiley & Sons (Canada) Ltd., 5353 Dundas Street West, Suite 400, Toronto, Ontario, M9B 6HB, Canada

John Wiley & Sons Australia Ltd., 42 McDougall Street, Milton, Queensland 4064, Australia

Wiley-VCH, Boschstrasse 12, D-69469 Weinheim, Germany

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

ISBN 978-1-118-15377-2 (Paperback)

ISBN 978-1-118-15379-6 (ePDF)

ISBN 978-1-118-15378-9 (Mobi)

ISBN 978-1-118-15380-2 (ePub)

For Han Jin-duk

Whose life cannot be given back

Preface

An American diplomat in Seoul once aptly described North Korea as an intelligence black hole. Its submarines can be tracked, its pedestrians followed from space, and its newspapers read. But how does the analyst sift this material if he doesnt know how the captains get their orders, what the pedestrians talk about when they disappear into buildings, or whats in the reports sent to decision makers?

Now consider how dangerous North Korea is. It is dedicated, in its ruling partys constitution at least, to overthrowing its rival, South Korea, and unifying the peninsula. It has one of the worlds largest armies and is an enemy of the United States. The allies have long had the technical means to detect the build-up to a conventional attack. The danger of North Korea used to be expressed in terms of diminishing warning times, from days to hours. Now, however, North Korea is a nuclear-armed state with an arsenal of biological and chemical weapons and a large number of special forces that could be on top of the South Koreans before they knew it. Recent incidents came with no warning: In 2010, a South Korean frigate was sunk with the loss of 46 lives, in a nighttime attack that was almost certainly North Korean; in the same year, four people were killed when North Korean artillery shelled a South Korean island; in April 2011, the computer system at a South Korean financial institution crashed in what investigators and intelligence officials claimed was a North Korean cyber attack.

Media analysts claim such attacks represent demands for cash, positioning before negotiations, warnings not to be ignored, nonspecific attention seeking, unifying the people after the announcement about succession of the next leader, muscle-flexing by the next leader, revenge for an earlier clash that the North Korean navy lost, and so on. In short, they dont know. They dont know why these attacks happened, couldnt tell they were going to happen, and dont know what will happen next.

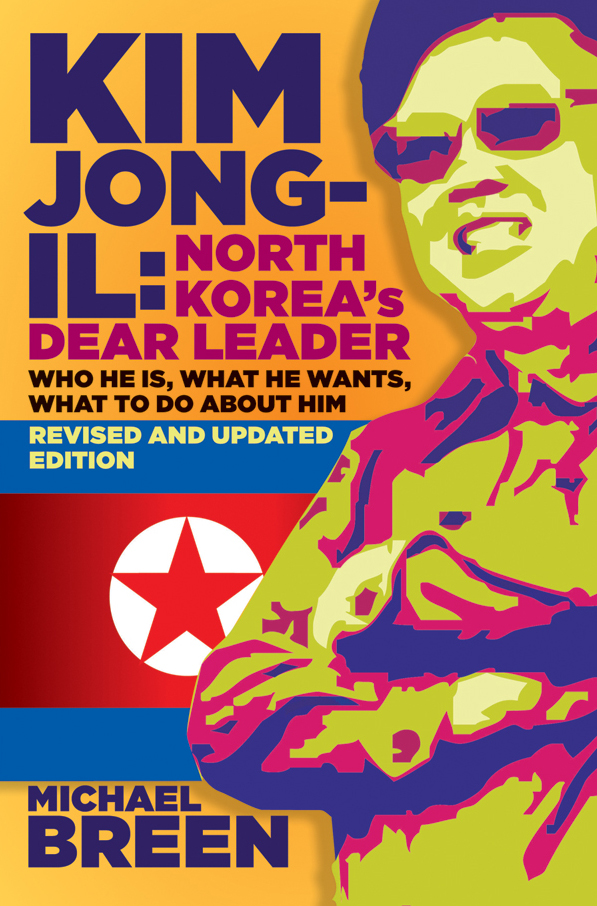

The heart of this dark mystery for the past two decades was Kim Jong-il. Until his death in December 2011, he was the absolute leader of this nation of twenty-three million, a role he inherited in 1994 from his father, Kim Il-sung, who ruled from the foundation of the country in 1948. As Kim Jong-il ailedhe had a stroke in 2008he identified his third son, Kim Jong-un, as the man to succeed him. The world got its first long look at this young man, who is still in his 20s, at his father's funeral, where he was flanked by elderly party leaders and generals in uniform. Scenes of sobbing North Koreans, some of them sincere and some no doubt making sure they appeared duly miserable, were played around the world. Analysts made a stab at answering the question on everyone's mind: How will the new Kim fare? No one knows.

Kim Jong-il died, allegedly of a heart attack on his private train brought on by hard work, the week the updated version of this book reached the stores. We may have to revise these lines about the new leader a few months later. Or, we may be asking the same questions about the same North Korea at Kim Jong-un's funeral 60 years from now. What we can say with some certainty, though, is that the young Kim will have to defer, possibly even take orders from, those old men around him for some time to come. If he crosses them, and certainly if he tries any reforms in the near future, he will himself be pushed out. That is because the North Korean elites share a dilemma: They know that if they open their country, as they must to join the rest of the world and improve the welfare of their people, they will be letting in the virus that will ultimately destroy them. Their choice is to protect themselves and keep their people down. For as long as they do this, they need Kim Jong-un. Thus they will continue with more of the same. And that means that, just as Kim Jong-il kept the memory of his own father aliveindeed, he appointed the late dictator as president-for-eternityso Kim Jong-un must call on his father's ghost to justify his own leadership. Kim Jong-il, we may say, hasn't gone yet. This book is about him.

I write from Seoul, the capital of South Korea. My home is a two-minute walk from the presidential Blue House. This perspective places me firmly in favor of talks over warfare. My views and feelings toward Kim and North Korea are influenced of course by proximity, but they are at the same time distinct from those of my neighbors inasmuch as I am not Korean. The two Koreas are rare nations in the world that have had almost zero racial mixing for several thousand years and where therefore nationality is defined with reference to race. North Koreas version of this is as politically incorrect in the modern world as it gets. The particular temptation for South Koreans in considering Kim Jong-il is the narcotic of racial brotherhood, which engenders eventual forgiveness of even the most egregious North Korean offense. This aside, South Korean attitudes that were shaped under dictators by propaganda, tales of the 19501953 war, and proximity, have shifted with democracy and wealth. South Koreans have extended themselves to forgive, propose reconciliation and offer help, and examine themselves when it is rejected. This journey leaves them both drawn to and repulsed by North Korea, swinging from a preference one day for liberal engagement and food aid to the conviction the next day that Kim Jong-il must be taken out. They find his regime loathsome in regard to its human rights and inability to care for its people and manage the economy. But they fear the chaos of change. They also worry about the demonizing of Kim by foreigners, a necessary precursor to military action, because they live too close. Sometimes, too, they are embarrassed because he is, after all, Korean.