Thank you for downloading this Simon & Schuster eBook.

Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases, deals, bonus content and other great books from Simon & Schuster.

C LICK H ERE T O S IGN U P

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

Contents

As always, for Lady Susan

Acknowledgments

I learned of George Washingtons journey to the new nation several decades ago while preparing a newspaper piece for a special Presidents Day section. His diary, which figures centrally in this book, recounted his decision to stay only at public inns and taverns, even though that meant that he often had to endure bad food and uncomfortable beds. He complained about the unsatisfactory accommodations for him and his horses. Only later did I come to appreciate the larger significance of this extraordinary trip, which took him to all original thirteen states. The research for this project involved reconstructing Washingtons tours of the United States, from New Hampshire to Georgia, following as best I could the same roads that he had traveled.

As my readers will discover, the president encountered many interesting and generous men and women along the way. So did I. The list of people who offered guidance includes Mary V. Thompson, a research historian at Mount Vernon, who repeatedly came to my rescue when I needed precise information on topics such as the theater in New York City in 1789 and the details of the lives of Washingtons slaves. Edward G. Lengel, editor of the Washington Papers, a magnificent project that is the foundation of all modern Washington scholarship, provided insights and encouragement at key points.

Several others gave me welcome direction, often over coffee when perhaps they did not realize how much they were helping to advance the project. Although the interpretation of Washingtons journey is entirely my own, I thank those who offered welcome and helpful guidance along the way: David Hancock, Christopher W. Brooks, Bill Brown, Steve Hindle, Roy Ritchie, Hermann Wellenreuther, John Brewer, Gideon Manning, Alan Taylor, Carole Shammas, Doug Bradburn, Patrick Griffin, Edward Stehle, Walter Woodward, David Cressy, Naill Kirkwood, Howard Pashman, Larry Hewes, Harvey (Amani) Whitfield, and Michael Lammert. Several people helped me locate illustrations, for which I owe them a considerable debt of gratitude: Dawn Bonner at Mount Vernon, Ashley Cataldo at the American Antiquarian Society, Joyce Baker at the Gibbes Museum of Art in Charleston, and Bea Ross of the Congregation Jeshuat Israel at the Touro Synagogue.

Northwestern University generously funded my research. I also acknowledge two marvelous institutions, the California Institute of Technology and the Huntington Library and Garden, for their support at key moments. At Caltech, Francine Tise patiently explained the mysteries of modern technology. Two gifted Northwestern students, Andrew Jarrell and Nicholas Ruge, collected valuable research materials. It was a pleasure working with all these people.

During autumn 2013, I delivered the Gay Hart Gaines Lectures at Mount Vernon. In 2014, I gave the James Marsh Lectures at the University of Vermont. I used these occasions to test my interpretation. The people who attended these events raised many excellent questions, for which I thank them. I also thank Christopher Celenza, director of the American Academy in Rome, who provided me with an opportunity to write in a splendid environment. Just when I thought I had finished the book, my editor, Alice Mayhew, pushed me to sharpen the argument and reveal more clearly the full dimensions of the presidents genius. She was correct in every case, and I owe her a great debt for helping me to recount a compelling story.

Susan Breen joined George Washington and me on the full journey. Without her insights, I would have missed much of what the president was trying to tell me about the new nation.

T.H. Breen

Greensboro, Vermont

February 4, 2015

Prologue

Untrodden Ground: Defining a New Political Culture

Throughout history, revolutions have usually ended badly. The course of these events is all too familiar. After success on the battlefield, a sense of solidarity born of dreams of liberation and reform gives way to disappointment and fragmentation. We do not usually think of the American Revolution in these terms. After all, our revolution did not end badly. The American people not only achieved independence, but also established a constitutional republic that has survived for more than two centuries.

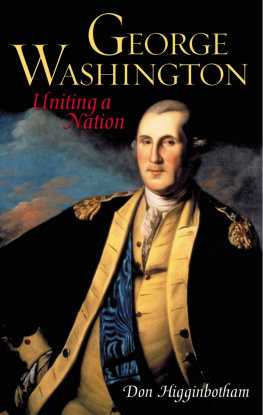

We owe a lot to George Washington for this striking achievement. During his first term as president of the United States, he recognized the critical need to preserve the original goals of the Revolution. Fearful that the promise of national independence would slip away, he insisted on creating a powerful union capable of overcoming internal division. George Washingtons Journey recounts how he devised a boldly original plan to promote a strong central government during a time of political peril.

We study Washingtons journey today to recapture a sense of national purpose and unity that has gone missing from the ongoing conversation between our countrys elected leaders and the American people. It is true, of course, that Washingtons appeal for solidarity often fell on deaf ears. Unlike him, we know what the future held for the country after his presidency. Civil war almost destroyed the union he worked so hard to preserve. Local concerns have repeatedly trumped comprehension of the common good. Political parties have stimulated heated debate, which sometimes has led to the utter paralysis of the government. Whatever the threats to the nation have been, Washingtons travels remind us, now more than ever before, of the enduring need for the American people to pull together to recover the original promise of the Revolution. For us, that is his message.

I

During his first days in office, Washington organized a journey that shaped how the American people perceived their relationship with the new federal government. Drawing on his immense popularity, Washington envisioned an ambitious tour of the United States as a way to transform the abstract language of the Constitution into a powerful, highly personal argument for a strong union. At a key moment in our countrys history when the very survival of the new system could not be taken for granted, he took to the road to discover what was on the minds of the American people and, more, share with them his own expansive vision for republican government in this country.

By reaching out to the people where they lived and worked, Washington invited ordinary men and women to imagine themselves not simply as victorious revolutionaries or as individuals who had managed briefly to establish a loose confederation of states, but, rather, as citizens of a powerful new republic. His decision sparked a far-reaching conversation about the future of the entire country that still echoes throughout the public forum. As he explained repeatedly, the success of the new nation was in the hands of the people. All they had to do, Washington declared, was to give their full support to the union for which they had fought.

The tour of the new republic began early in Washingtons first term as president. Between 1789 and 1791, Washington organized several separate journeys, which carried him to all the original thirteen states. Although travel by coach was extremely difficult, he covered thousands of miles and on at least two occasions was involved in potentially fatal accidents.

Next page