For My Father

Evoe

OF PUNCH

Introduction

by Richard Holmes

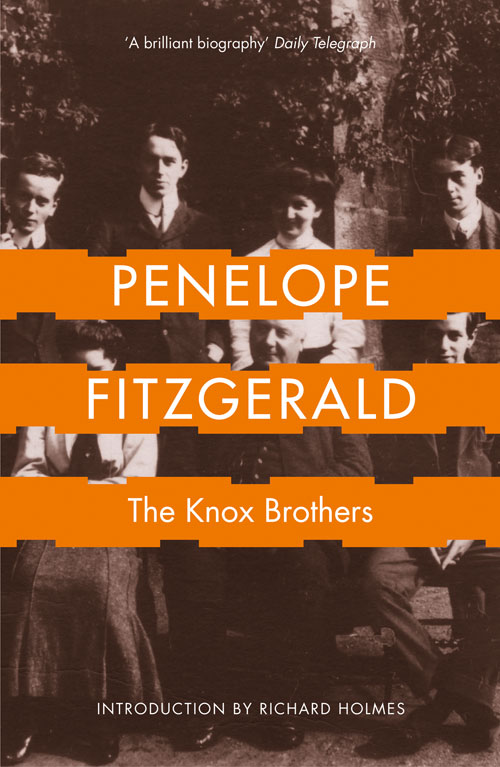

P ENELOPE FITZGERALDS MARRIED NAME, the name under which she became loved and celebrated as a novelist, subtly disguised her true inheritance. For Fitzgerald was really a Knox, and this marked her invisibly or perhaps, indelibly all her long life, and especially in her later and astonishingly creative years.

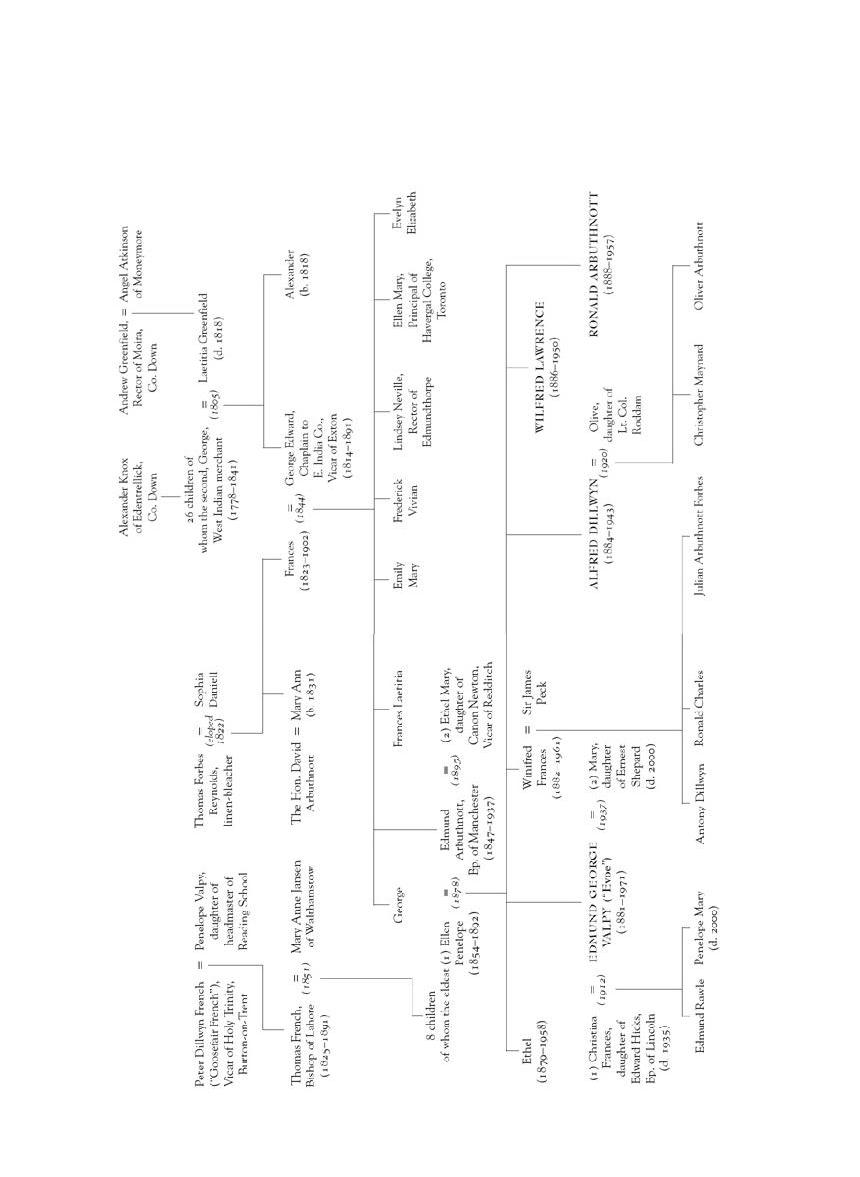

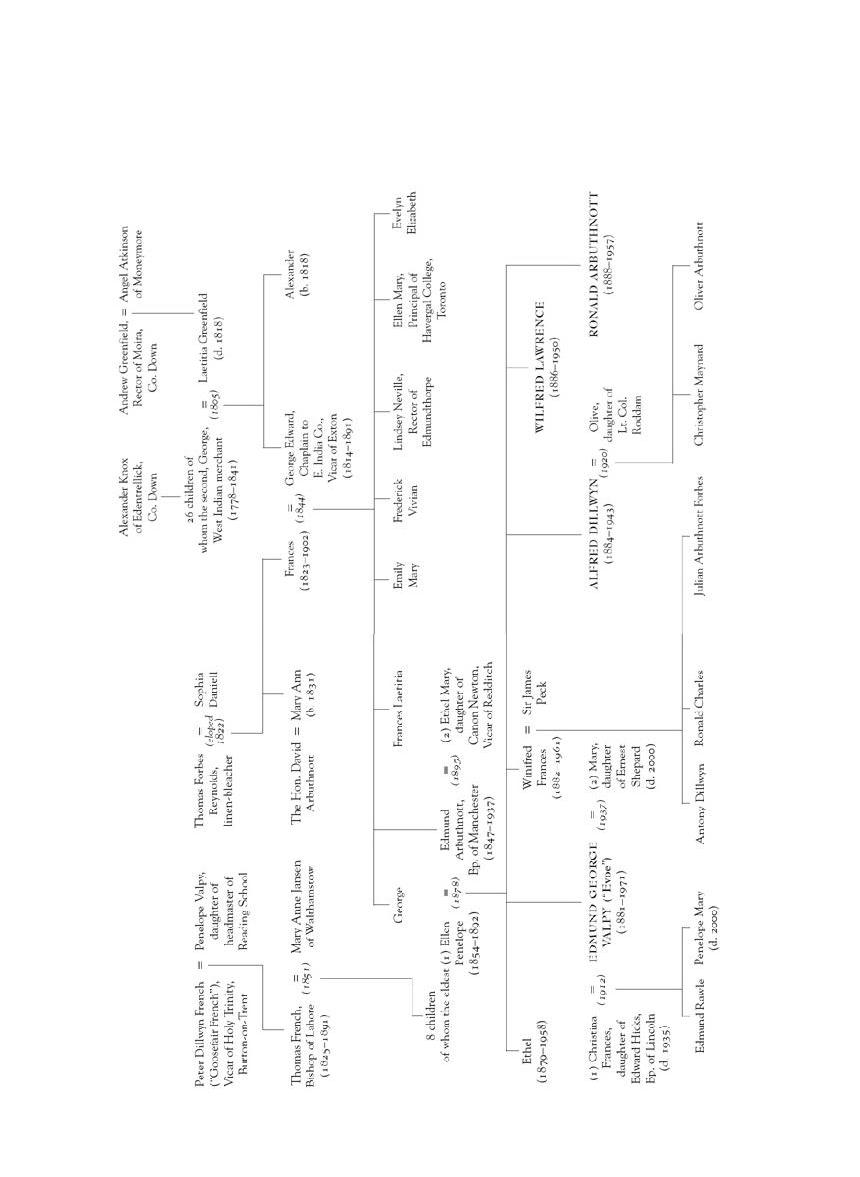

As a Knox, she was descended from one of the great intellectual, Anglo-Catholic clans of late Victorian England. She was born Penelope Mary Knox in December 1916. Her great-grandfather had been the missionary Bishop of Lahore; her grandfather was Bishop of Manchester; one uncle was the writer and translator of the Bible Monsignor Ronald Knox (like Newman, a Roman Catholic convert); and her father was for sixteen years the much-admired editor of Punch, at a perilous time (19321948) when the magazine was still a great institution of national identity, like The Times or Speakers Corner or Harrods (and shared some of the attributes of each).

The Knox Brothers is her remarkable tribute to this family inheritance. It is a strikingly original group biography, and a highly engaging piece of family history, written with extraordinary wit and shrewdness: a funny, tender, clever book. But it is very much more than that. One might call it a study in a vanished civilization, and I am sure that it is destined to become a twentieth-century classic.

Its place in Penelope Fitzgeralds work is intriguing. The biography first appeared in 1977, when she was sixty. But because of her unusual, late-flowering literary career, it was in fact one of her earliest books, and seems intimately connected with her self-discovery as a writer. In taking the measure of her formidable family background (and this is hardly a work of pious memorial), Penelope Fitzgerald found a narrative style, a fascination with human character, and a series of moral preoccupations which seemed to release the whole flow of her fiction.

Her late start as a novelist was something Penelope Fitzgerald was frequently, and often wistfully, quizzed about for instance at the Hay-on-Wye Festival of 1994. She was famous for the modesty of her replies, and one explanation was that she had simply been too busy with life, until she happened to enter a Ghost Story competition organized by The Times in Christmas 1974, when she had just turned fifty-eight.

(Her winning story, The Axe was published in The Times Anthology of Ghost Stories in 1975, and subsequently collected posthumously in The Means of Escape. Its victim, an ancient and one might say an almost disembodied office clerk called Singlebury, is introduced with a gentle but slightly unnerving irony, that is already recognisably hers. Singlebury had, however, one distinguishing feature, very light blue eyes, with a defensive expression, as though apologizing for something which he felt guilty about, but could not put right. The fact is that he was getting old. Getting old is, of course, a crime of which we grow more guilty every day.)

More searching interviews (such as that by Hermione Lee, for BBC Radio 3, in 1997) revealed how directly her first novels drew on a mass of autobiographical material, stored up over forty years, and awaiting a moment of release. The pattern of her life suggested a long, slow period of imaginative and intellectual assimilation, in preparation for a literary career that she had always hoped for, but never quite expected.

Tantalizing glimpses of her as a teenager appear in later chapters of The Knox Brothers. But, characteristically, she always refers to herself in the third person, as the niece or the daughter. If you blink, you will miss them. From these we learn that she was largely brought up in literary London, in Hampstead and Regents Park, with an elder brother, and her fathers circle of brilliant acquaintances such as Belloc and AP Herbert. She attended (unhappily, one gathers) Wycombe Abbey, near Oxford, one of the most academically demanding of public schools for girls. This too appears in a wonderful, single-paragraph cameo in chapter seven.

In 1935, when she was still only eighteen, her mother died of cancer, which devastated the household. She writes characteristically of her father, Edmund Knox, at this time of overwhelming grief. It was many years before Eddie could bring himself to mention her name directly, even to his own son and daughter. At the time, he asked the proprietors of Punch for a short leave of absence, and an understanding that he would not be writing any funny pieces for the paper that year. She says not a word of her own (the daughters) feelings, but only notes that her uncle Ronald, when attending the Anglican funeral, being a Catholic insisted on kneeling alone in the aisle. (p. 208)

Penelope Knox took a First at Somerville College, Oxford. She then worked in a series of institutions, great and small (the wartime BBC, a childrens drama school, a Suffolk bookshop) having married Desmond Fitzgerald, a lawyer, in 1941. The family was mildly bohemian, in the Knox tradition, and were happy to live on a Thames barge, while taking occasional summer holidays in Italy and one memorable winter holiday in Russia. All of these experiences appear, transformed but recognisable, as settings for her later novels.

In 1976, the year following the ghost story, her husband Desmond died after a long illness. Penelope Fitzgerald never wrote directly about this time. But it was now, in amazingly rapid succession, that she produced in just five years, no less than six books which must have been, in some sense, bursting within her. The fascinating thing is that the first two were not novels, but biographies.

She had been working for some time on her life of the pre-Raphaelite artist Edward Burne-Jones (1975), perhaps as a distraction from her own immediate pain and unhappiness. It was inspired, she said, by Burne-Joness stained-glass window of the Last Judgement, in St Philips, Birmingham. No agitation here, the dwellers on the earth simply stand waiting for their sentence. The whole effect depends on the late afternoon sun slanting through the glorious red of the massed angels wings. It is a window for Evensong. (p. 271) The biography is lively, engaging, and well-researched, with a particularly striking picture of Burne-Joness domestic life. But it also has the slight narrative stiffness, the uncertain deployment of materials, and uneven emotional tone, of a first book.

Nothing could be less true of The Knox Brothers, which appeared just two years later in 1977. Somehow, an artistic transformation has taken place. From the very first chapter, with its amazing and moving tale of her great-grandfather the missionary Bishop, sailing calmly out to his lonely death from Muscat, in a fishing boat, under a blazing sun, with his book-bag, the biography is pitched with a narrative assurance, a gentle irony, and a delight in curious anecdote, which proved to be the hallmarks of Fitzgeralds clear and silvery style.

Reading The Knox Brothers now, some twenty-five years after it was written, one is delighted by its period charm, its playful narration, and its barely repressed sense of mischief. But one is also struck by its technical ambition. For Fitzgerald, the obvious choice was to write mainly about the two famous literary figures of the family: her father Edmund and her uncle Ronald. Here were two well-known, but nicely contrasted brothers, who provided a perfectly balanced biographical subject, of great interest and wide appeal.

Next page