Published in 2016 by the Feminist Press at the City University of New York

The Graduate Center

365 Fifth Avenue, Suite 5406

New York, NY 10016

feministpress.org

First Feminist Press edition 2016

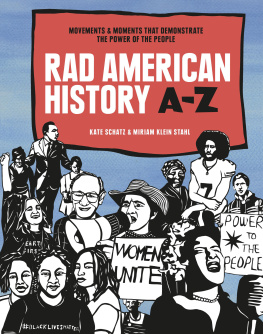

Introduction copyright 2016 by Kate Schatz

Preface and Notes on the Tales copyright 1978 by Ethel Johnston Phelps

Kamala and the Seven Thieves, The Young Head of the Family, The Legend of Knockmany, The Lute Player, The Shepherd of Myddvai and the Lake Maiden, The Squires Bride, The Enchanted Buck, and Mastermaid copyright 1978 by Ethel Johnston Phelps

Cover and interior illustrations copyright 2016 by Suki Boynton

Copyright information continues on

All rights reserved.

This book was made possible thanks to a grant from New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew Cuomo and the New York State Legislature.

No part of this book may be reproduced or used, stored in any information retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without prior written permission of the Feminist Press at the City University of New York, except in case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

First printing October 2016

Cover design, text design, and illustrations by Suki Boynton

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this title.

For Rachael, Jenny,

and Nancy,

who love tales of magic

and adventure

Table of Contents

Guide

CONTENTS

KATE SCHATZ

I love this bookbut thats no surprise.

Im a feminist author, an amateur historian. A literature lover, an activist mama. Ive always loved fairy tales and folktales. I was a womens studies major. Of course I love this book!

Point is, Im an easy audience.

So I put this book to a real test. I announced to my almost-seven-year-old daughter (six and three-quartersshe likes to be precise) that we have new bedtime reading material. And together we read the stories in Kamala, night after night. We curled up in her top bunk, her little warm body pressing in close to mine when we met the ogre, stiffening in anticipation when the prince ate the apple, relaxing and laughing in triumph when Kamala tricked the thieves. We giggled at the clueless giant and guffawed at the horse-bride. And in the grand tradition of eager-yet-sleepy children all over the world, each night she begged for just one more story. One night I said no, its late, and turned off the lamp. In the not-quite-dark room, she picked up the book in quiet defiance and read on in the fading light. I let herhow could I not?

What might my daughter dream of after devouring these tales? I wondered. Would she become a talented queen in disguise, on a journey to save her husband? Brave Smac with her magic fan? A radiant maiden emerging from a lake? With each story, the possibilities expand.

Kamala is the second volume in a series derived from the classic Tatterhood and Other Tales, which was originally published by the Feminist Press in 1978. (The new Tatterhood was published in 2016, with an introduction by Gayle Forman.) That same year, the Susan B. Anthony dollar was approved for circulation, Buffy Sainte-Marie was on Sesame Street, and San Francisco held the first-ever Take Back the Night march. Audre Lordes The Black Unicorn, bell hookss first book of poetry, and the Combahee River Collectives A Black Feminist Statement were all published. Judy Chicago worked to finish The Dinner Party. One hundred thousand people marched in Washington, DC, to demand an extension for the ratification of the ERA. And on an exceptionally hot California September day, I was born, right into the final years of second wave feminism.

In the grand tradition of Joan Didion, I believe that these events are all totally, utterly connected. They are the conditions that produced Tatterhood and Kamala and they are the conditions that produced me.

During my childhood I read approximately one million books, but somehow I never encountered these stories. I now know, though, that many of my friends did grow up with Tatterhood and Other Tales: they recall it as an absolute favorite that was beloved. One friend is currently reading her tattered original copy to her daughter, hoping it doesnt fall apart before they get to the end.

That well-worn copy (and the thousands of others that live in homes around the world) is why the Feminist Press needed to bring these stories back now. The four-volume series makes something old new againwhich is, after all, what fairy tales have been doing for centuries.

There are reasons that certain stories are told over and over, across generations. We return to these master narratives, revising them to reflect new times and cultures. Fairy tales imprint messages, mores, and lessons; they explore crucial human experiences: love, loss, battle, the struggle to support a family. They teach us how to treat a friend or a stranger. How to outsmart those who seek to control you. Fairy tales are entertainment and warning, distraction and guide. Illusion and instruction. Their core messages do not stop being relevantbut it matters which stories we tell.

In Kamala and the Seven Thieves, Kamala is frustrated by her lazy husband, who chooses gossip over work. The story tells us that being a resourceful woman, Kamala sat down to think of a plan to make the best of their situation. Boom. There you go. Rather than sit down and await help like the passive princesses so often depicted, Kamala takes action. The women in these stories are resourcefuland is that not the most ancient of female truths? The importance of being resourceful, of making do, and making good with what you havewhen what you have is profoundly limited. When you are denied access to wealth, literacy, property, your own reproductive systemand you still make something of yourself and your situation.

More often than not, the women in these stories are providers, via magic, wits, courage, or some combination thereof. When the Lake Maiden emerges from the water, eager to wed the shy shepherd, she brings more than just an enchanted lovely selfshe brings a herd of valuable cattle and enough knowledge of healing herbs that shes able to influence generations of physicians. Protagonists like Smac and the Young Head of the Family save their families, while women like Kamala, Oonagh, and the Lute Playing Queen ultimately (spoiler alert!) save the day and their husbands. Quite often these crafty characters figure out how to work patriarchy, using sexist assumptions that men make about them to their own advantage.

Many of the stories in Kamala explore traditional love and romance, with females acting as eager bridesthe twist, though, is that the women have agency. In The Enchanted Buck, Lungile is a young woman whose first marriage prospect was ruined by accusations of witchcraft. After discovering that a beautiful buck is actually a powerful chief, the young man tells her: You will be loved and honored if you will be my bride. Its the next line that gets me: Lungile consented with great joy. Lungile consented. With great joy.

Here is a question that haunts me after reading these tales: Who cast the spell over fairy tales, stealing these fierce, bawdy stories from the mouths of mothers and transforming the strong girls at the center into damsels in distress? Who gathered up these exhilarating myths and then added one thousand cups of sugar, the tears of a lonely princess, and the sweat from the brow of a woodsman? What foul sorcerer removed independence, spice, sass, cunning, and wit? There are answersHans, those brothers, Walt, five thousand years of patriarchybut really, the more important question is: How do we