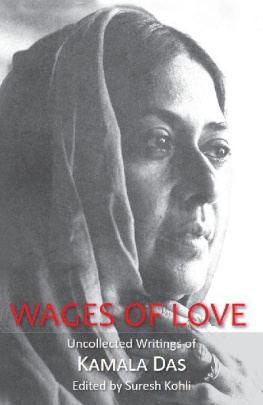

WAGES OF LOVE

UNCOLLECTED WRITINGS OF

KAMALA DAS

Edited by

Suresh Kohli

Contents

KAMALA WAS AN ENIGMA EVEN to herself. She liked to dramatize, imagining narratives on the spur of the moment. People were often shocked by her actions and movements without realizing that such acts served the intended purpose. The same applied to her writings. She wrote things she did not herself believe in, but the consummate actor that she was, she negated the aura of disbelief.

We had been distinctly and distantly close from the time I first visited her, if memory serves me right, way back in 1968 in her Bank House, Backbay Reclamation apartment in Bombay. I happened to have reviewed her first collection of verse, Summer in Calcutta . Needless to say, the book inculcated in me a strong desire to meet the woman who dared to indulge in confessionals. Do I need to say it was love at first sight, an infatuation that lasted till her death on 31 May 2009, exactly two months after her seventy-fifth birthday that I had the privilege to attend on her specific invitation?

She had shifted to Pune by then, looked after and cared for by her youngest of three sons and his small family living two floors below her apartment. The bond between us had become thicker, not necessarily because I made a reasonably satisfactory documentary on her in English, but because of the somewhat frequent visits to Pune to research at the National Film Archives. Indulging in nostalgia replete with references to friends and foes, she talked about some new poems and, realizing that she hadnt published a new book of verse in a while, suggested we do a book jointly, threatening to write a new poem for the collection every day. And she did precisely that, though not necessarily one a day since she would be on sedatives. She left the selection to me. Her son Jaisurya provided me access to a bundle of her unpublished poems as well. It was a lot of verse, much more indulgent and death-infested than ever before.

When I searched for my own publishable verse from my files I could not pick up more than forty. So there had to be an equal number from her treasure as well. Once the decision had been made I also decided to engage her in a long recorded conversation encompassing our years of infatuation. Unfortunately, when I started transcribing it there appeared gaps in the recording which was due to a faulty tape, but, mercifully, there had still been enough of it to includefilling up the blanks with the help of video recordings during the filming of the documentaryin Closure , our joint collection which was published by HarperCollins India and has had two more reprints in quick succession.

After her death, Jai thrust some more files on me. Meanwhile, I wrote to my brother Prof. Devindra Kohli in Germany and Merrily Weisbord in Canada, who had then been engaged in a biography of sorts of Kamala, to forward any unpublished material of hers in their archives. From that and other material emerged A Kept Woman and Other Stories to which I declined to append my name.

I wanted to call this volume I Studied All Men after a short piece she had contributed to The Illustrated Weekly of India in September 1971, then edited by Khushwant Singh, and reproduce from it some paragraphs to make Kamala laugh wherever she might be now. But the publishers thought otherwise and suggested Wages of Love.

Kamala Das was of course a master storyteller in Malayalam with about 1,500 stories to her credit. Most of these need to be collected and translated into English. One is certain such gems of absorbing writing lie abandoned in various nooks and corners demanding resurrection. This collection contains only a segment that she passed onto me on that fateful day in Pune, and some that Jai couriered subsequently. Not all has come in here. There are many other tattered, typed sheets on decaying paper, many other unpublished verses that one hopes to redeem some other day.

S URESH K OHLI

SHE HAD HEARD OF THE killer Babu from her own security guard. Babu was fair-skinned and bow-legged. He had a pockmarked face. He charged thirty thousand rupees for each killing. Finally, after much debating within, she decided to engage him for getting her work done.

It was indeed difficult for her to escape from her house unnoticed. But avoiding her servants and her chauffeur she left by a by-lane catching an autorickshaw.

She was panting and out of breath, but she kept her face hidden, the purdah pulled over it revealing only her mouth.

Through the narrow lanes past the Jewish synagogue and on the cobbled, meandering roads, the rickshaw sped on and stopped at the bookshop that displayed her own books of poetry.

The glare of the midday sun hurt her eyes. She was not recognized in her newly acquired Muslim attire.

She looked around. There were the usual shabby antiques garnered from the impoverished families of Malabarthe pewter jugs, the yellow-faced clocks, the gramophones and the rosewood dolls. The junk that outlived its owner, more hardy than skeletons... she recollected the dim light of the lamp in the hall of her ancestral house. She remembered the village that denied her access due to her conversion to Islam. No, it is of no use remembering those years. She has been reincarnated. The past possibly cannot welcome her.

When she clambered up the steps to enter the bookshop, a pale shadow separated itself from the shadowy interior and walked towards her. She was perspiring heavily.

New books have arrived. Latin American authors, he said.

I did not come here to buy books. I was looking for a man named Babu, a young man with a pockmarked face.

The shop owner pushed a chair towards her. There are at least a dozen Babus in this locality. There is the Babu who sells antiques. His shop is a few yards awayyou can see bell metal lamps hanging outside. Another Babu sells large bronze utensils.

Oh no, I was not looking for lamps or utensils, she cried. The Babu I am looking for is a hired killer.

For a few moments the man maintained silence. Then he whispered, I cannot believe that you would seek the services of a killer.

She nodded her head. Her eyes filled with tears, Yes I need a killer, she said weakly.

Madam, you seem to be very decent, very kind... who told you of this Babu?

My security guarda police constable appointed by the government to protect my life. Babu is a fair-skinned young man. He kills for thirty thousand rupees. Goes to jail but is bailed out by powerful politicians. When he is outside the jail he kills again. That is the only trade he has learnt.

Madam, only this minute I have recognized you. I was telling myself, I have surely heard this voice many times. I have not seen you after your conversion to Islam. Please sit down. I shall go and get some coffee for you.

No, I do not need any coffee. Thank you all the same, she said.

What about a Coca-Cola?

No, nothing. I really must be going back. All of them must be searching for me. Can you call an autorickshaw for me?

Later as he helped her into the auto he asked gently, Who is the enemy you need to kill?

I am the one who is to be killed, she said as the auto turned and sped along the cobbled road...

A MAN RETURNING HOME AT night from a simple cremation, having thanked everyone: we could simply call him Achhan. Because, only three children in the city know his value. They call him Achha.

Sitting in the bus among strangers, he went over every second of that day.

Woke up in the morning to her voice. Unniye, dont go on sleeping covered up like that. Its Monday. She was calling the eldest son. She then moved to the kitchen, her white sari crumpled. Brought me a big glass of coffee. Then? What happened then? Did she say anything that should not be forgotten? However much he tried, he could not remember. Dont go on sleeping covered up like that. Its Monday. Only that line lingered. He chanted it to himself, as if it was a prayer. If he forgot it, the loss would be unbearable.