Table of Contents

For my wife Mary Breeding, our precious children Diya, Dhyan, and Dheer and for individuals and families who transcend race, religion, and ethnicity.

We are the world. The future is ours.

CONTENTS

T HE UNITED STATES has had more than a dozen female presidents. Betty Boop in 1932, Polly Bergen in 1964, Natalie Portman in 1996, Christina Applegate in 1998, Lisa Simpson in 2000 and Julia Louis-Dreyfus in 2012 are among those who made it to the Oval Office.

All in fiction, of course.

The theme of female American presidents began soon after the United States empowered women to vote with the Nineteenth Amendment to its Constitution in 1919, ratified and certified in 1920. Four years later, the silent science-fiction film The Last Man onEarth showed a woman as president of the United States after a disease known as masculitis has killed off every fertile man on earth over the age of fourteen.

In Pat Franks 1959 science-fiction novel Alas, Babylon, Josephine Vanebruuker-Brown becomes president because she is the only member in the line of succession to survive nuclear war. In ABCs 2012 TV series Scandal, Melody Margaret Grant becomes the first female president of the United States after the assassination of President-elect Francisco Vargas.

You get the picture. In several movies, books and television series, a woman becomes president only because men die or they have been marginalized. In 1995, the TV series Sliders aired an episode entitled The Weaker Sex, where Teresa Barnwell played Hillary Clinton as president of the United States in an alternative universe where women are in charge. That was the closest women got to being commander-in-chief based on merit it had to happen in a galaxy far, far away. Back on earth, though, more often than not, it takes the death of a spouse either from illness, or being killed in an alien attack (Mars Attacks!) for the Oval Office to fall into a womans lap.

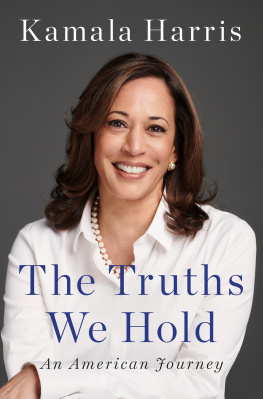

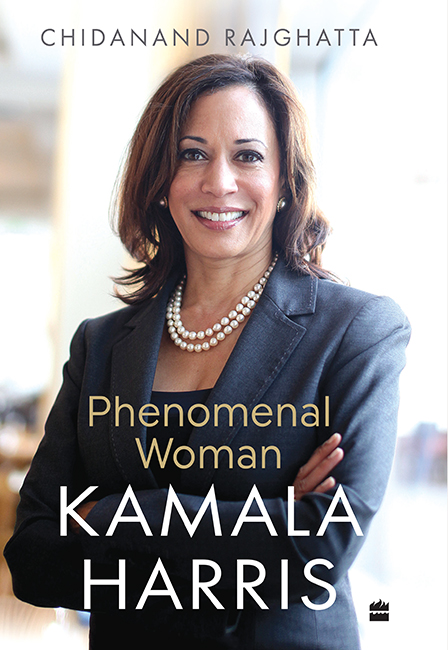

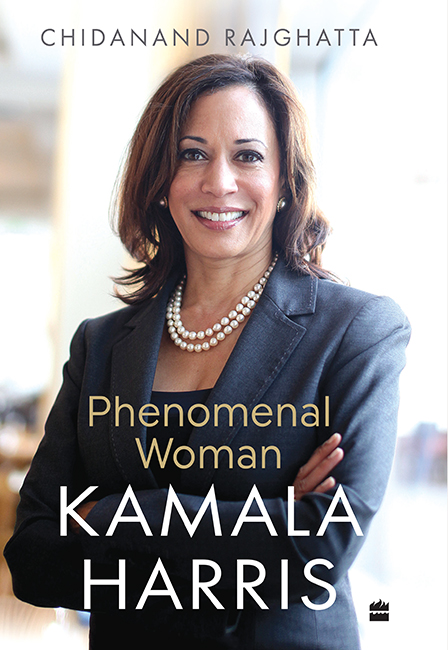

On the rare occasion a woman becomes the president on her own steam, she is shown struggling to balance the job and the family a requirement men are rarely expected to meet. In the 1964 comedy Kisses for My President, Leslie McCloud eventually discovers that she is pregnant and resigns to devote herself full-time to her family. In the 1985 ABC sitcom Hailto the Chief, President Julia Mansfield has to manage her political fortunes while raising her family. In real life, American women have seldom come anywhere near the White House, except as a first lady. Until now. Until Kamala Harris, a presidential candidate in the 2020 election, became the countrys forty-ninth vice president a heartbeat away from the Oval Office.

One hundred years after the suffragist movement led to women getting the right to vote through the Nineteenth Amendment, America is at a unique moment in its history. The year 2020 was annus horribilis in so many ways but it was a peak moment for female political empowerment. American women finally smashed the glass ceiling.

Several had tried before, but only three had come close Hillary Clinton being the one who came nearest. Democratic vice-presidential nominee Geraldine Ferraro in 1984 and Republican vice-presidential nominee Sarah Palin in 2008 both lost on the coattails of presidential candidates Walter Mondale and John McCain, respectively, eventually fading into oblivion.

Hillary Clinton won the national popular vote comfortably in 2016, but was thwarted by an archaic electoral college system that is suffused with white male primacy and patriarchy. The electoral college, which actually elects the president, gives representation to thinly populated states and rural areas (which are white majority areas) without regard to demographics; two senators per state, regardless of population.

The expressions glass ceiling and heartbeat away from the White House/Oval Office feature in current political discourse more than at any time in history, given the breakthrough in 2020 on the gender, race and age front. Coined by management consultant Marilyn Loden at a panel discussion appropriately titled Mirror, Mirror on the Wall at the 1978 Womens Exposition in New York, glass ceiling refers to the sometimes-invisible barrier to success that many women come up against in their careers. Two years before Lodens crack about the glass ceiling, the Jimmy Carter campaign threw out the term heartbeat away from the presidency into the public domain in a television ad promoting a strong running mate, Walter Mondale. When you know that four of the last six vice presidents have wound up as president, who would you like to see a heartbeat away from the presidency? it asked. After two election cycles that gave Ronald Reagan two terms as president, the same expression was used with concern in 1988 to ask if George H.W. Bushs running mate Dan Quayle really had the goods to succeed him if it came to that. Quayle was widely seen as a lightweight dummy surpassed only in 2008 by the mediocrity of John McCains running mate Sarah Palin. But generally with women running mates it was not a question of whether they had the intelligence to lead the mightiest country in modern history, but whether they had the machismo. Somehow, in patriarchal America, the presidency has always been considered a mans job. Men have been at it for over 240 years.

By the time Hillary lost, a victim of relentless right-wing demonization, sexism, and her own political mistakes there was a sense of inevitability that another woman may take a shot at the White House soon, shatter that glass ceiling, and come not just within a heartbeat of the presidency, but sit in the Oval Office itself a feat she narrowly missed. Not only was the United States becoming less white and more brown thanks to immigration and changing demographics, more American women were turning up at the polls than American men, changing both race and gender dynamics. This was particularly true of Black women, who constitute only about 7 per cent of the population but tend to vote at higher rates than other groups 60 per cent and above in the past five presidential cycles. They are also the Democratic Partys most loyal voters. In 2016, 94 per cent of Black women voted for Democrat Hillary Clinton the highest rate of any group, far more than the 80 per cent of Black men who went for her, and nearly double that of white women. The onus was on the Democratic Party, whose platform is more favourable to womens rights and aspirations. Simple political calculus made a compelling case for a female nominee, if not at the top of a Democratic ticket, then as a running mate. Maybe both.

Hillary saw this coming in a concession speech on the night after Trump nicked her out of the White House through the electoral college. Eyes glittering with tears that were being held back, she told supporters, I know we have still not shattered that highest and hardest glass ceiling, but someday someone will, and hopefully sooner than we might think right now.

In fact, it was starting to happen even as she spoke.

Across the country in California, Kamala Harris was so confident of winning the senate race on the night Hillary Clinton lost in November 2016 that her campaign had scheduled a victory party at the Exchange LA nightclub in Downtown Los Angeles. Two giant nets with the familiar red, white and blue balloons were packed into the ceiling. Liquor was flowing at the cash bar. There was an air of expectation and exultation among the Democratic laity. With Kamalas victory in the bag, all eyes were trained on the big screens streaming the results of the presidential elections. Most polls had pointed to a comfortable win for Hillary Clinton and the west coast liberal literati and glitterati were ready for a double party.