All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Printed in the United States of America.

Cataloging-in-Publication data for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

Da Capo Press books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the U.S. by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 11 Cambridge Center, Cambridge, MA 02142, or call (800) 255-1514 or (617) 252-5298, or e-mail .

FOREWORD

THE death of Jeremiah Curtin robbed America of one of her two or three foremost scholars. Mr. Curtin, who was by birth a native of Wisconsin, at one time was in the diplomatic service of the Government; but his chief work was in literature. The extraordinary facility with which he learned any language, his gift of style in his own language, his industry, his restless activity and desire to see strange nations and out of the way peoples, and his great gift of imagination which enabled him to appreciate the epic sweep of vital historical events, all combined to render his work of peculiar value. His extraordinary translations of the Polish novels of Sienkiewicz, especially of those dealing with medieval Poland and her struggles with the Tartar, the Swede and the German, would in themselves have been enough to establish a first class reputation for any man. In addition he did remarkable work in connection with Indian, Celtic and other folk tales. But nothing that he did was more important than his studies of the rise of the mighty Mongol Empire and its decadence. In this particular field no other American or English scholar has ever approached him.

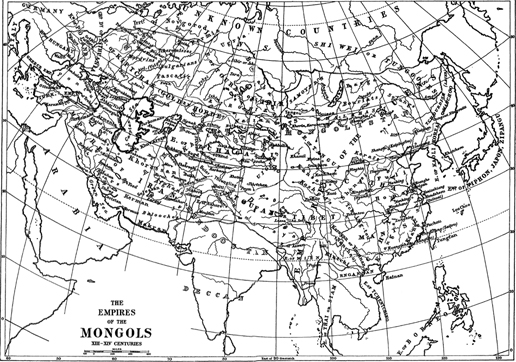

Indeed, it is extraordinary to see how ignorant even the best scholars of America and England are of the tremendous importance in world history of the nation-shattering Mongol invasions. A noted Englishman of letters not many years ago wrote a charming essay on the Thirteenth Centuryan essay showing his wide learning, his grasp of historical events, and the length of time that he had devoted to the study of the century. Yet the essayist not only never mentioned but was evidently ignorant of the most stupendous fact of the centurythe rise of Genghis Khan and the spread of the Mongol power from the Yellow Sea to the Adriatic and the Persian Gulf. Ignorance like this is partly due to the natural tendency among men whose culture is that of Western Europe to think of history as only European history and of European history as only the history of Latin and Teutonic Europe. But this does not entirely excuse ignorance of such an event as the Mongol-Tartar invasion, which affected half of Europe far more profoundly than the Crusades. It is this ignorance, of course accentuated among those who are not scholars, which accounts for the possibility of such comically absurd remarks as the one not infrequently made at the time of the Japanese-Russian war, that for the first time since Salamis Asia had conquered Europe. As a matter of fact the recent military supremacy of the white or European races is a matter of only some three centuries. For the four preceding centuries, that is, from the beginning of the thirteenth to the seventeenth, the Mongol and Turkish armies generally had the upper hand in any contest with European foes, appearing in Europe always as invaders and often as conquerors; while no ruler of Europe of their days had to his credit such mighty feats of arms, such wide conquests, as Genghis Khan, as Timour the Limper, as Bajazet, Selim and Amurath, as Baber and Akbar.

The rise of the Mongol power under Genghis Khan was unheralded and unforeseen, and it took the world as completely by surprise as the rise of the Arab power six centuries before. When the thirteenth century opened Genghis Khan was merely one among a number of other obscure Mongol chiefs and neither he nor his tribe had any reputation whatever outside of the barren plains of Central Asia, where they and their fellow-barbarians lived on horseback among their flocks and herds. Neither in civilized nor semi-civilized Europe, nor in civilized nor semi-civilized Asia, was he known or feared, any more, for instance, than the civilized world of today knows or fears the Senoussi, or any obscure black mahdi in the region south of the Sahara. At the moment, Europe had lost fear of aggression from either Asia or Africa. In Spain the power of the Moors had just been reduced to insignificance. The crusading spirit, it is true, had been thoroughly discredited by the wicked Fourth Crusade, when the Franks and Venetians took Constantinople and destroyed the old bulwark of Europe against the Infidel. But in the crusade in which he himself lost his life the Emperor Barbarossa had completely broken the power of the Seljouk Turks in Asia-Minor, and tho Jerusalem had been lost it was about to be regained by that strange and brilliant man, the Emperor Frederick II, the wonder of the world. The Slavs of Russia were organized into a kind of loose confederacy, and were slowly extending themselves eastward, making settlements like Moscow in the midst of various Finnish peoples. Hungary and Poland were great warrior kingdoms, tho a couple of centuries were to pass before Poland would come to her full power. The Caliphs still ruled at Bagdad. In India Mohammedan warred with Rajput; and the Chinese Empire was probably superior in civilization and in military strength to any nation of Europe.

Into this world burst the Mongol. All his early years Genghis Khan spent in obtaining first the control of his own tribe, and then in establishing the absolute supremacy of this tribe over all its neighbors. In the first decade of the thirteenth century this work was accomplished. His supremacy over the wild mounted herdsmen was absolute and unquestioned. Every formidable competitor, every man who would not bow with unquestioning obedience to his will, had been ruthlessly slain, and he had developed a number of able men who were willing to be his devoted slaves, and to carry out his every command with unhesitating obedience and dreadful prowess. Out of the Mongol horse-bowmen and horse-swordsmen he speedily made the most formidable troops then in existence. East, west and south he sent his armies, and under him and his immediate successors the area of conquest widened by leaps and bounds; while two generations went by before any troops were found in Asia or Europe who on any stricken field could hold their own with the terrible Mongol horsemen, and their subject-allies and remote kinsmen, the Turko-Tartars who served with and under them. Few conquests have ever been so hideous and on the whole so noxious to mankind. The Mongols were savages as cruel as they were brave and hardy. There were Nestorian Christians among them, as in most parts of Asia at that time, but the great bulk of them were Shamanists; that is, their creed and ethical culture were about on a par with those of the Comanches and Apaches of the nineteenth century. They differed from Comanche and Apache in that capacity for military organization which gave them such terrible efficiency; but otherwise they were not much more advanced, and the civilized peoples who fell under their sway experienced a fate as dreadful as would be the case if nowadays a civilized people were suddenly conquered by a great horde of Apaches. The ruthless cruelty of the Mongol was practised on a scale greater than ever before or since. The Moslems feared them as much as the Christians. They put to death the Caliph, and sacked Bagdad, just as they sacked the cities of Russia and Hungary. They destroyed the Turkish tribes which ventured to resist them with the merciless thoroness which they showed in dealing with any resistance in Europe. They were inconceivably formidable in battle, tireless in campaign and on the march, utterly indifferent to fatigue and hardship, of extraordinary prowess with bow and sword. To the Europeans who cowered in horror before them, the squat, slit-eyed, brawny horsemen, with faces like the snouts of dogs, seemed as hideous and fearsome as demons, and as irresistible by ordinary mortals. They conquered China and set on the throne a Mongol dynasty. India also their descendants conquered, and there likewise erected a great Mongol empire. Persia in the same way fell into their hands. Their armies, every soldier on horseback, marched incredible distances and overthrew whatever opposed them. They struck down the Russians at a blow and trampled the land into bloody mire beneath their horses feet. They crushed the Magyars in a single battle and drew a broad red furrow straight across Hungary, driving the Hungarian King in panic flight from his realm. They overran Poland and destroyed the banded knighthood of North Germany in Silesia. Western Europe could have made no adequate defense; but fortunately by this time the Mongol attack had spent itself, simply because the distance from the central point had become so great. It was no Christian or European military power which first by force set bounds to the Mongol conquests; but the Turkish Mamelukes of Egypt in the West, and in the East, some two score years later, the armies of Japan.