THE PUBLISHER GRATEFULLY ACKNOWLEDGES THE GENEROUS

SUPPORT OF THE AUGUST AND SUSAN FRUGE ENDOWMENT FUND

IN CALIFORNIA NATURAL HISTORY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF

CALIFORNIA PRESS FOUNDATION.

ROUGH-HEWN LAND

A Geologic Journey from California

to the Rocky Mountains

Keith Heyer Meldahl

University of California Press, one of the most distinguished university

presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing

scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its

activities are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic

contributions from individuals and institutions. For more information,

visit www.ucpress.edu.

For a digital version of this book, see the press website.

University of California Press

Berkeley and Los Angeles, California

University of California Press, Ltd.

London, England

2011 by the Regents of the University of California

Cataloging-in-Publication Data on file with the Library of Congress

19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of

ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (R 1997) (Permanence of Paper).

Cover image: Walker Lake, dunes in foreground, Mount Grant on horizon,

Great Basin, Nevada. Photo Scott Smith.

For Malcolm, Jim, Dan, and Jim

May your trails be dim, lonesome, stony, narrow, winding, and only slightly uphill.

May God's dog serenade your campfire, and may the rattlesnake

and the screech owl amuse your reverie.

May the Great Sun dazzle your eyes by day

and the Great Bear watch over you by night.

EDWARD ABBEY, 1971

Science is nothing but trained and organized common sense, differing from the

latter only as a veteran may differ from a raw recruit: and its methods differ from

those of common sense only as far as the guardsman's cut and thrust differ from

the manner in which a savage wields his club.

THOMAS H. HUXLEY, DARWIN DEFENDER AND EVOLUTION PROMOTER,

ON THE NATURE OF THE SCIENTIFIC METHOD, 1893

We are like a judge confronted by a defendant who declines to answer, and we

must determine the truth from the circumstantial evidence.

ALFRED WEGENER, DISCOVERER OF CONTINENTAL DRIFT,

ON THE CHALLENGE OF INTERPRETING THE EARTH'S PAST

FROM EVIDENCE IN ROCKS, 1929

Geology is not a totally exact science; you have to be creative. For the most part,

we don't have enough information to know everything we'd like to know about

what's going on. So you have to fill in the gaps, think outside the box, release your

inhibitionsand beer is one way to do that.

RICK SALTUS, U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY,

ON WHY GEOLOGISTS DRINK SO MUCH BEER, 2009

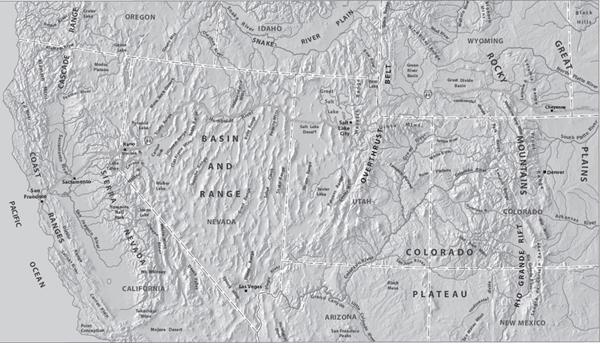

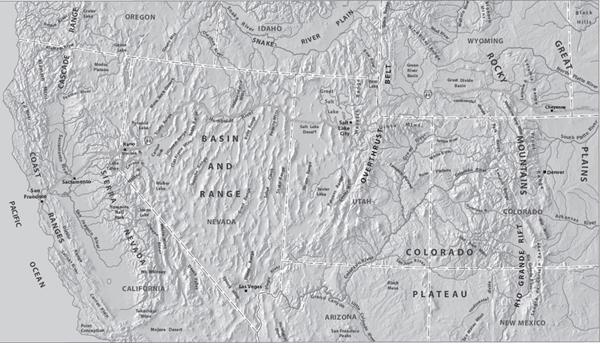

This book traverses a broad swath across the central western United States centered roughly on Interstate Highway 80. We begin at the Golden Gate by San Francisco, pass through California's Coast Ranges and Central Valley, ascend the Sierra Nevada, drop into the immense bowl of the Great Basin (part of the Basin and Range Province), climb the Rocky Mountains, and end on the western Great Plains.

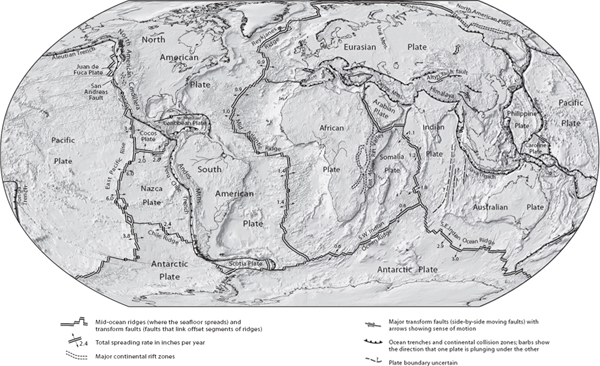

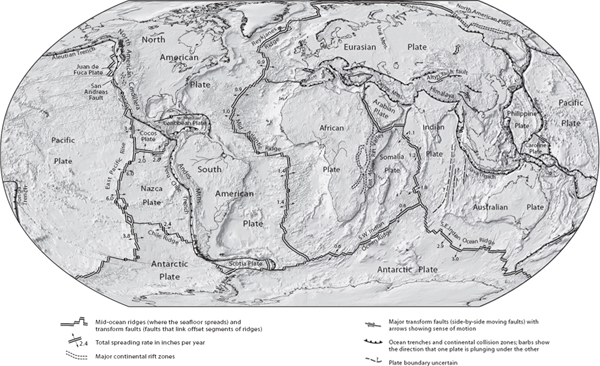

THE EARTH'S TECTONIC PLATES

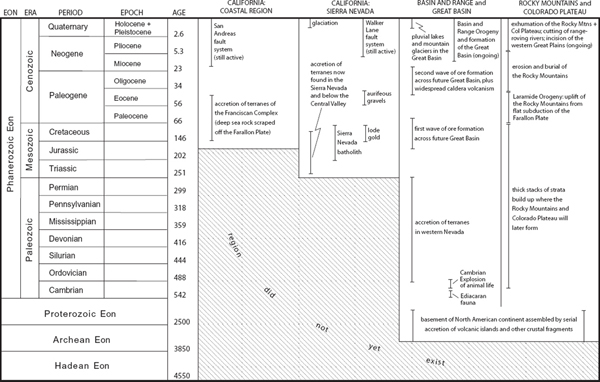

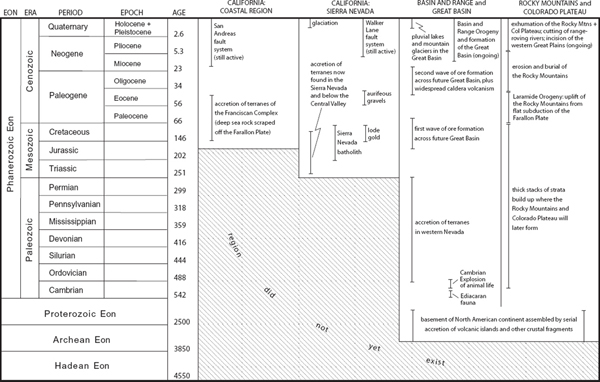

Major geologic developments in the American West from the California coast to the Rocky Mountains. Geologic ages are in millions of years. Note that the vertical scale varies; older geologic intervals cover greater time spans than do younger intervals.

PREFACE

The mountains are calling me and I must go.

JOHN MUIR, 1873

Twenty-seven years ago, I climbed into my 67 Chevy on the east coast and aimed it toward the Pacific Ocean. Everything I owned fit in the trunk with room to spare for twelve quarts of motor oil that would be gone before I reached California. I had a fresh geology degree tucked between my ears, but when it came to the American West, I was as ignorant as a stone. The world west of the Rockies was terra incognita to me; the only Rocky Mountains I had seen were on paper, the only Grand Canyon, a photograph in a book.

The Great Plains did their best to entertain me, putting on earnest displays of corn, soybeans, and wheat. I counted combines to stay alert, while the Chevy smoked oil to pass the time. Then Colorado's Front Range soared up on the horizon. I had never seen anything like it. Raised in the East and schooled in the Midwest, the biggest thing I had ever laid eyes on was a Silurian reef. Hey, I thought, now that's a mountain! Soybeans fell behind. The air thinned and cooled. Dark pines cascaded down the slopes. Higher up, the pines thinned, revealing naked rock bent into grotesque contortionstestimony to the forces that pushed up the Rockies some sixty million years ago. Over the next days, every bend in the road brought something magnificent into view. Crossing the Rocky Mountain roofline of the continent, I traversed a world that seemed closer to the sky than to the Earth, where the lowest valleys lie higher than the highest peaks back east. I followed the Colorado River from its source across the broad plateau that bears its namea great platform, improbably high, clawed by red-rock canyons of otherworldly beauty. Dropping off the Colorado Plateau, I entered the Basin and Range Province, a landscape rhythmically cleaved by north-south trending mountain ranges that rise in immense silence from broad, gravelly basins. Nature's rules seemed reversed here. In the East, rivers get bigger downstream; here, they shrank and disappeared downstream, sucked up by the bottomless aridity. In the East, trees eventually end as you go up the mountains. Here, the trees ended as I came down, for in the arid West the mountains poke like wooded islands out of seas of desert air.

Onward I went, delighting in the grand, implacable emptiness of it all. Beyond the wall of the unreal city, Edward Abbey wrote, there is another world waiting for you. It is the old true world of the deserts, the mountains, the forests. I found that old true world in the American West. Civilization, which has paved or tilled over most of the nation east of the Rockies, here lay scattered in towns and cities separated by vast, wild spaces. In God's wildness lies the hope of the world, John Muir declared. And best of all (with apologies to Muir, who spent much of his life defending the world's biggest plants), there were few plants in this arid sector of the nationin other words, not too much annoying biology to obscure the rocks, the database of the Earth's history.

I didn't know it then, but that first trip across the American West would reset the arc of my life. Through the years that followedthrough graduate studies, tenure, grants, research papers, and the annual rhythms of teachingthe West closed its grip on me. Now, the thinnest of excuses to go to the mountains have given way to no excuses at all. With moves so familiar that I could do them in my sleep, I carry my gear from the garage to the truck, kiss my wife goodbye (unless she's decided to come along), and head once again into the wild, pulled there by the hooks that the West sunk into me long ago.