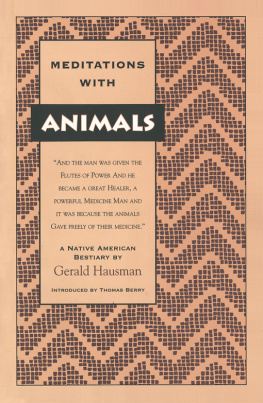

MEDITATIONS WITH ANIMALS:

A Native American Bestiary

from the voices of

Creek, Natchez, Chickasaw, Winnebago, Haida, Tlingit,

Kwakuitl, Zuni, Navajo, Apache,

Santo Domingo, Sioux, Osage,

Anasazi

Collected & adapted by

Gerald Hausman

Illustrated by

Liese Jean Scott

Foreword by Thomas Berry

Afterword by Dr. Michael W. Fox

BEAR & COMPANY

SANTA FE, NEW MEXICO

This book is for Lorry, who waited

while things waited while things

were getting done.

AUTHORS NOTE

Hopefully it should be clear that such artificial designations as People of the Plain and People of the Lake are more poetical than factual. This is not to say these references are not helpful; they are, that is why I have used them. But they are not strictly accurate as any Native American scholar knows. For instance, many tribes lived by rivers; it was a good way to live. Woodland tribes might also be called, in some cases, mountain tribes. Desert peopleApaches, for instanceranged vigorously about the mountains, the plains, and the deserts. Most tribes, in their own language, referred to themselves as the People, not the People of.

I also wish to add the following commentthe meditation passages in this book are quite literally meditations. They arose out of deep thought and were written in a trance-like state, which may account for their stylistic rhythm. Later I accurately researched and sometimes corrected the thread of my thoughts. I did not, however, alter their voice.

Foreword: Returning to Our Native Place

We are returning to our native place after a long absence, meeting once again with our kin in the earth community. For too long a while we have been away somewhere, entranced with our industrial world of wires and wheels, concrete and steel, and our unending highways where we race back and forth in unending frenzy.

The world of life, of spontaneity, the world of dawn and sunset and glittering stars in the dark night heavens, the world of wind and rain, of meadow flowers and flowering streams, of hickory and oak and maple and spruce and pineland forests, the world of desert sand and prairie grasses; and within all this the eagle and the hawk, the mockingbird and the chickadee, the deer and the wolf and the bear, the coyote, the raccoon, the whale and the seal, and the salmon returning upstream to spawn.

All this, the wilderness world recently rediscovered, with heightened emotional sensitivity, is an experience not too distant from that of Dante meeting Beatrice at the end of the Purgatorio where she descends amid a cloud of blossoms. So long a wait for Dane, so aware of his infidelities, yet struck anew and inwardly pierced as when, hardly out of his childhood, he had first seen Beatrice. The ancient flame was lit again in the depths of his being. In this meeting, Dante is describing not only a personal experience but the experience of the entire human community at the moment of reconciliation with the divine after the long period of alienation and of human wandering away from the true center.

Something of this feeling of intimacy we now experience as we recover our presence within the earth community. This is something more than working out a viable economy, something more than ecology, much more than Deep Ecology seems to be aware of or moved by. This is a sense of presence, a realization that the earth community is a wilderness community that will not be bargained with; nor will it simply be studied or examined or made an object of any kind; nor will it be domesticated or trivialized as a setting for vacation indulgence, except under duress and by oppressions which it cannot escape. When this does take place in an abusive way, a terrible vengeance awaits the human; for when the other living species are violated so extensively, then the human itself ceases to be a viable life form.

If the earth does grow inhospitable in such a manner and to such a degree, it is primarily because we have lost our sense of courtesy toward the earth and its inhabitants, our sense of gratitude, our willingness to recognize the sacred character of habitat, our capacity for the awesome, the numinous quality of every earthly reality. We have even forgotten our primordial capacity for language at the elementary level of song and dance wherein we share our existence with the animals and with all natural phenomena. Witness how the Pueblo Indians of the Rio Grande enter into the eagle dance, the buffalo dance, and the deer dance; how the Navajo become intimate with the larger community through their dry-paintings and their chantway ceremonies; how the peoples of the Northwest express their identity through their totem animals; how the Hopi enter into communication with desert rattlesnakes in their ritual dance. This mutual presence finds expression also in poetry and in story form, especially in the trickster stories of the Plains Indians where Coyote performs his never-ending magic. Such modes of presence to the living world we still carry deep within our selves beyond all the suppressions and even the antagonism imposed by our cultural traditions.

Even within our own Western traditions at our greater moments of expression, we find this presence, as in Hildegard of Bingen, Francis of Assisi, and even in the diurnal and seasonal liturgies. The dawn and evening liturgies especially give expression to the natural phenomena in their numinous qualities. Also, in the bestiaries of the medieval period we find a special mode of drawing the animal world into the world of human converse. In their symbolisms and especially in the moral qualities associated with the various animals, we find a mutual revelatory experience. These animal stories have a playfulness about them, something of a common language, a capacity to care for each other. Yet these movements toward intensive sharing with the natural world were constantly turned aside by a spiritual aversion, even by a sense that humans were inherently cut off from any true sharing of life. At best they were drawn into a human context in some subservient way, often in a derogatory way when we projected our own vicious qualities onto such animals as the wolf, the rat, the snake, the worm, the insects in all their admirable qualities. We seldom entered their wilderness world with any true empathy.

The change is begun, however, in every phase of human activity, in all our professions and institutions. Greenpeace on the sea and Earth First on the land are asserting our primary loyalties to the community of earth. Gary Snyder with his poetry and Paul Winter with his music are communicating with the entire span of natural beings. Paul Winter especially is responding to the cry of the wolf and the song of the whale in his music. Roger Tory Peterson has brought us intimately into the world of the birds. Joy Adamson has entered into the world of the lions in Africa. Dian Fossey has entered into the social world of the gentle gorilla. John Lilly has been profoundly absorbed into the consciousness of the dolphin. Farley Mowat has come to an intimate understanding of the grey wolf of North America. Others have learned the dance language of the bees. Even the songs of the crickets have been studied.

What is fascinating about these intimate academic associations with the various animals is that we are establishing not only an acquaintance with the general life and emotions of the various species but also an intimate rapport, even an affective relationship, with individual animals within their wilderness context. Names are given to individual whales. Indeed, individual wild animals are entering into history. This can be observed in the burial of Digit, the special gorilla friend of Dian Fossey. Dians own death by human assault gives abundant evidence that we may be safer in the wilderness context of the animals than with humans in civilized society.

Next page