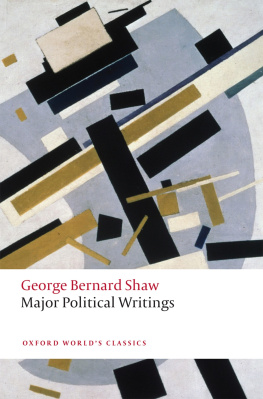

THE BERNARD SHAW LIBRARY

PLAYS POLITICAL

Bernard Shaw was born in Dublin in 1856. Essentially shy, yet he created the persona of G.B.S., the showman, satirist, controversialist, critic, pundit, wit, intellectual buffoon and dramatist. Commentators brought a new adjective into English: Shavian, a term used to embody all his brilliant qualities.

After his arrival in London in 1876 he became an active Socialist and a brilliant platform speaker. He wrote on many social aspects of the day: on Commonsense about the War (1914), How to Settle the Irish Question (1917) and The Intelligent Womans Guide to Socialism and Capitalism (1928). He undertook his own education at the British Museum and consequently became keenly interested in cultural subjects. Thus his prolific output included music, art and theatre reviews, which were collected into several volumes: Music in London 18901894 (3 vols., 1931); Pen Portraits and Reviews (1931); and Our Theatres in the Nineties (3 vols., 1931). He wrote five novels and some shorter fiction including The Black Girl in Search of God and some Lesser Tales and Cashel Byrons Profession, both published in Penguins.

He conducted a strong attack on the London theatre and was closely associated with the intellectual revival of British theatre. His many plays fall into several categories: Plays Pleasant; Plays Unpleasant; comedies; chronicle-plays; metabiological Pentateuch (Back to Methuselah, a series of plays) and political extravaganzas. G.B.S. died in 1950.

BERNARD SHAW

PLAYS POLITICAL

THE APPLE CART

ON THE ROCKS

GENEVA

Definitive Text

UNDER THE EDITORIAL SUPERVISION OF

DAN H. LAURENCE

PENGUIN BOOKS

PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

27 Wrights Lane, London W 8 5 TZ , England

Viking Penguin Inc., 40 West 23rd Street, New York, New York 10010, USA

Penguin Books Australia Ltd, Ringwood, Victoria, Australia

Penguin Books Canada Ltd, 2801 John Street, Markham, Ontario, Canada L 3 R IB 4

Penguin Books (NZ) Ltd, 182190 Wairau Road, Auckland 10, New Zealand

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England

The Apple Cart published separately in Penguin Books 1956

This collection published in Penguin Books 1986

The Apple Cart: Copyright 1930, 1931, George Bernard Shaw. Renewal copyright 1957, 1958, The Public Trustee as Executor of the Estate of George Bernard Shaw

On the Rocks: Copyright 1934, George Bernard Shaw. Renewal copyright 1961, The Public Trustee as Executor of the Estate of George Bernard Shaw

Geneva: Copyright 1938, 1946, 1947, George Bernard Shaw. Renewal copyright 1965, 1973, 1974, The Public Trustee as Executor of the Estate of George Bernard Shaw

All rights reserved

All business connected with Bernard Shaws plays is in the hands of The Society of Authors, 84 Drayton Gardens, London SW 10 9 SB (Telephone: 01-373 6642), to which all inquiries and applications for licences to perform should be addressed and performing fees paid. Dates and places of contemplated performances must be precisely specified in all applications.

Applications for permission to give stock and amateur performances of Bernard Shaws plays in the United States of America and Canada should be made to Samuel French Inc., 45 West 25th Street, New York, New York 10010

Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publishers prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

ISBN: 978-0-14-196371-6

The Apple Cart

A Political Extravaganza

WITH

Preface

THE APPLE CART

Composition begun 5 November 1928; completed 29 December 1928. First published in German translation, as Der Kaiser von Amerika, 1929. Published in English, 1930. First presented in Polish at the Teatr Polski, Warsaw, on 14 June 1929. First presented in English at the Festival Theatre, Malvern, on 19 August 1929.

Pamphilius |  | Private Secretaries to the King |  | Wallace Evennett |

Sempronius | Scott Sunderland |

Boanerges (President of the Board of Trade) Matthew Boulton

Magnus (King of England) Cedric Hardwicke

Alice (The Princess Royal) Eve Turner

Proteus (Prime Minister) Charles Carson

Balbus (Home Secretary) Frank Moore

Nicobar (Foreign Secretary) Clifford Marquand

Crassus (Colonial Secretary) Julian dAlbie

Pliny (Chancellor of the Exchequer) Aubrey Mallalieu

Lysistrata (Powermistress-General) Eileen Beldon

Amanda (Postmistress-General) Dorothy Holmes-Gore

Orinthia Edith Evans

Queen Jemima Barbara Everest

Mr Vanhattan (American Ambassador) James Carew

PeriodThe Future

ACT I An Office in the Royal Palace. A Summer Morning. 11 a.m.

An Interlude: Orinthias Boudoir. The Same Day. 3.15 p.m.

ACT II A Terrace overlooking the Palace Gardens. Later in the Afternoon

Preface

The first performances of this play at home and abroad provoked several confident anticipations that it would be published with an elaborate prefatory treatise on Democracy to explain why I, formerly a notorious democrat, have apparently veered round to the opposite quarter and become a devoted Royalist. In Dresden the performance was actually prohibited as a blasphemy against Democracy.

What was all this pother about? I had written a comedy in which a King defeats an attempt by his popularly elected Prime Minister to deprive him of the right to influence public opinion through the press and the platform: in short, to reduce him to a cipher. The Kings reply is that rather than be a cipher he will abandon his throne and take his obviously very rosy chance of becoming a popularly elected Prime Minister himself. To those who believe that our system of votes for everybody produces parliaments which represent the people it should seem that this solution of the difficulty is completely democratic, and that the Prime Minister must at once accept it joyfully as such. He knows better. The change would rally the anti-democratic royalist vote against him, and impose on him a rival in the person of the only public man whose ability he has to fear. The comedic paradox of the situation is that the King wins, not by exercising his royal authority, but by threatening to resign it and go to the democratic poll.

That so many critics who believe themselves to be ardent democrats should take the entirely personal triumph of the hereditary king over the elected minister to be a triumph of autocracy over democracy, and its dramatization an act of political apostasy on the part of the author, convinces me that our professed devotion to political principles is only a mask for our idolatry of eminent persons. The Apple Cart exposes the unreality of both democracy and royalty as our idealists conceive them. Our Liberal democrats believe in a figment called a constitutional monarch, a sort of Punch puppet who cannot move until his Prime Ministers fingers are in his sleeves. They believe in another figment called a responsible minister, who moves only when similarly actuated by the million fingers of the electorate. But the most superficial inspection of any two such figures shews that they are not puppets but living men, and that the supposed control of one by the other and of both by the electorate amounts to no more than a not very deterrent fear of uncertain and under ordinary circumstances quite remote consequences. The nearest thing to a puppet in our political system is a Cabinet minister at the head of a great public office. Unless he possesses a very exceptional share of dominating ability and relevant knowledge he is helpless in the hands of his officials. He must sign whatever documents they present to him, and repeat whatever words they put into his mouth when answering questions in parliament, with a docility which cannot be imposed on a king who works at his job; for the king works continuously whilst his ministers are in office for spells only, the spells being few and brief, and often occurring for the first time to men of advanced age with little or no training for and experience of supreme responsibility. George the Third and Queen Victoria were not, like Queen Elizabeth, the natural superiors of their ministers in political genius and general capacity; but they were for many purposes of State necessarily superior to them in experience, in cunning, in exact knowledge of the limits of their responsibility and consequently of the limits of their irresponsibility: in short, in the authority and practical power that these superiorities produce. Very clever men who have come into contact with monarchs have been so impressed that they have attributed to them extraordinary natural qualifications which they, as now visible to us in historical perspective, clearly did not possess. In conflicts between monarchs and popularly elected ministers the monarchs win every time when personal ability and good sense are at all equally divided.

Next page