Fourth Estate

an imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

First published in 2018 in Australia and New Zealand

by Finch Publishing Pty Limited

This edition published in 2019

by HarperCollinsPublishers Australia Pty Limited

ABN 36 009 913 517

harpercollins.com.au

Copyright Vicki Laveau-Harvie

The right of Vicki Laveau-Harvie to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her under the Copyright Amendment (Moral Rights) Act 2000.

This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced, copied, scanned, stored in a retrieval system, recorded, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

HarperCollinsPublishers

Level 13, 201 Elizabeth Street, Sydney NSW 2000, Australia

Unit D1, 63 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, Auckland 0632, New Zealand

A 53, Sector 57, Noida, UP, India

1 London Bridge Street, London, SE1 9GF, United Kingdom

Bay Adelaide Centre, East Tower, 22 Adelaide Street West, 41st floor, Toronto, Ontario M5H 4E3, Canada

195 Broadway, New York NY 10007, USA

ISBN 978 1 4607 5825 0 (paperback)

ISBN 978 1 4607 1196 5 (ebook)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of Australia

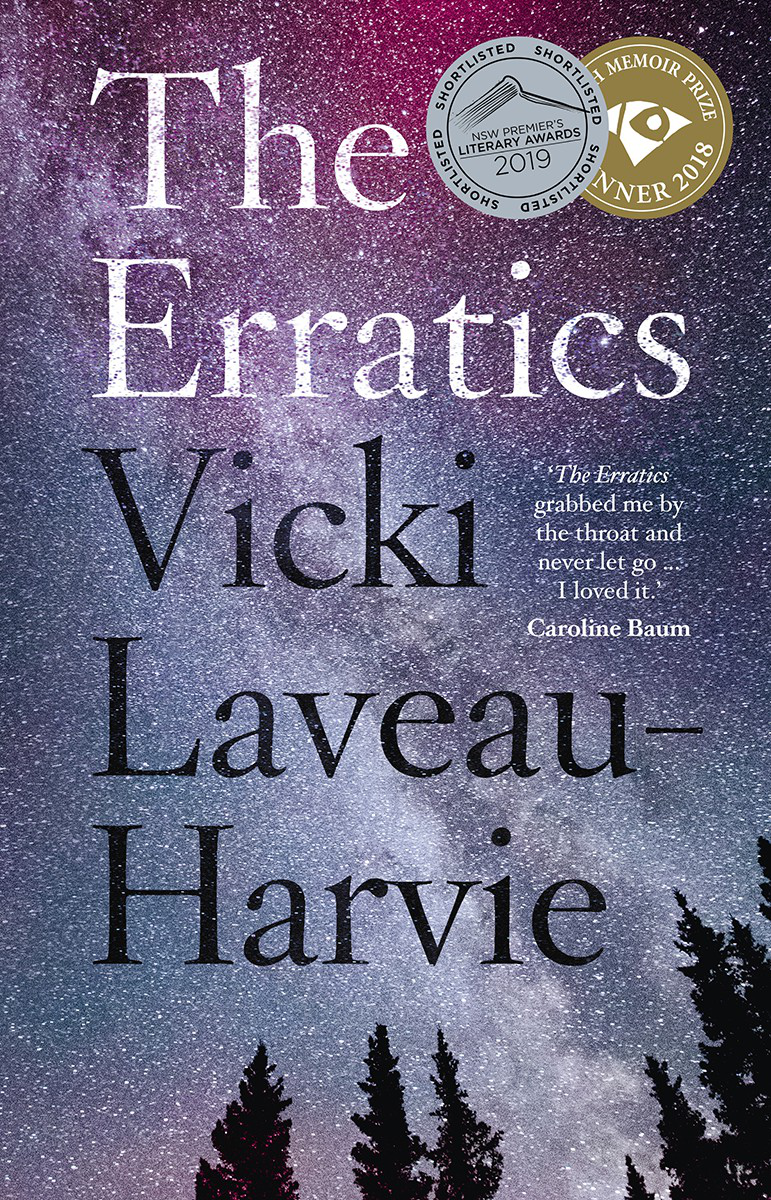

Cover design by Mark Campbell, HarperCollins Design Studio

Cover image by Justin Mullet/ stocksy.com/ 1908356

Author photograph by Michael Chetham

Tens of thousands of years ago, the Cordilleran Ice Sheet snaked down the east side of the Alaskan Rocky Mountains, through what is now the province of Alberta in Canada, and into the US state of Montana. As it moved, it deposited gigantic rocks called Erratics along its path. These form what is known as the Foothills Erratic Train.

One of those huge boulders sits in the foothills a few miles from the Canadian town of Okotoks, in a landscape of uncommon beauty.

Countless years ago, the Okotoks Erratic fell in on itself and became unsafe to climb upon. It dominates the landscape, roped off and isolated, the danger it presents to anyone trespassing palpable and documented on the signs posted around it.

For Laurence and Simon,

and for Irene

Chapter 1

My sister unhooks the chart from the foot of my mothers bed and reads.

My mother is not in the bed. My sister takes her pen, which is always to hand, around her neck or poked into a pocket and, with the air of entitlement of a medical professional, writes MMA in large letters at the bottom of the chart.

MMA.

Mad as a meat-axe.

My sister learned this expression from me yesterday. She has latched onto it like a child wresting a toy from another.

We have come to visit my mother, in rehab for a broken hip in this prairie hospital, a place that could be far worse than it is. It is set down here, plain and brown, on flat farmland, but the foothills start rolling westward just outside town and you see them from the windows. They roll on, smooth, rhythmic and comforting, until they bump into the stern and inscrutable face of the Rockies eighty miles thataway.

In summer the fields are sensible, right-angled squares of sulphur-yellow and clean, pale green, rapeseed and young wheat. In winter the cold will kill you. Nothing personal. Your lungs will freeze as Christmas lights tracing the outlines of white frame houses wink cheerfully through air so clear and hard it shatters.

MMA, I say. They wont know what that means. You dont say that here in Southern Alberta, even in urban centres. Its a down-underism, an Antipodianism. Maybe theyll see that on the chart and give her some medication called MMA and kill her.

Do we care? my sister asks. She hangs the chart back on the foot of the bed as my mother wheels into the room, gaunt, her favourite look, with a black fringe and bobbed hair. Hats off for carrying that off at 94. Her sinewy hands coerce the wheels of her chair forward faster than you are supposed to go if you need this chair.

She is wearing a hospital gown and a pair of fuchsia boxer shorts. Not hers. Obviously not hers.

She remarks that it is strange that she cannot have her own things to wear, that she must wear this strange outfit. We dont think to question. We believe in strange. We believe whatever. Theres no other way to go at this.

We have run the nurses station gauntlet to get to her. We have announced ourselves at the counter as her daughters, on our first visit to this rehab ward. We are her daughters we say, when challenged about why we are in this corridor.

No, youre not, the nurse says, not even looking up from her papers.

But we are. Were sure.

No, she insists. She only had one daughter and she died a long time ago. Now she has none.

My sister cries out from the heart, startling me. Look at me, she cries. Do I look dead?

I dont think she is looking too good, but there is something more pressing. Why, I ask her, are you the daughter who gets to exist? Even if youre dead now. Not to put too fine a point on it but if anyone should get to be dead, its me. I was born first.

The physio strolling by stops to ask who we are and what the matter is. We stare at her, wanting to say all that is the matter, wanting to unroll the whole carpet of what is the matter and smooth it out, drawing attention to the motifs, combing the fringed edges into some order, vacuuming the patterned surface until clarity emerges. We wonder how to begin.

They are saying, the nurse tells the physio, that theyre the duchesss daughters. But she has no children.

Youve got it wrong, the physio says. Little bird of a person, youd never know it of her, but she had eighteen kids. Imagine, eighteen. And only one boy. Heartbroken she was. Told me herself. In tears. Oh, she had kids all right. Nobody around when you need them though.

I draw breath. I can work with this. See, I say to the nurse, there you go. We cant speak for the others, but wed like to see her.

Just in case were having too much fun with this, lets go back a notch in time. Only a little while, dont be afraid, not far enough to get caught in the starry wheeling vertigo of the slow-mo free-fall no-up-and-no-down that is the more distant past. We will go there chronology has its uses but not just yet.

Some weeks earlier then. The beginning of winter.

When winter comes, summer is the memory that keeps people going, the remembrance of the long slanting dusk, peonies massed along the path, blossoms as big as balloons, crimson satin petals deepening to the black of dried blood in the waning light, deer on the lawns, stock still. Some people here, not transplants from the city like my parents, still make preserves in the summer, crab-apple jelly, tomato chutney, apple butter. They keep the jars safe through the autumn months, when the hay is rolled and the young coyotes practise yipping at the moon from the edge of the stubbled fields, to eat when the snow flies.

My parents live in paradise, twenty acres with a ranch house on a rise, nothing between you and the sky and the distant mountains. Overlapping cedar shingles on the roof that will last for generations or until the house falls down.