RIBBON OF SAND

The Amazing Convergence of the Ocean and the Outer Banks

John Alexander and James Lazell

Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill

1992

Published by

Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill

Post Office Box 2225

Chapel Hill, North Carolina 27515-2225

a division of

Workman Publishing Company, Inc.

225 Varick Street

New York, New York 10014

1992 by John Alexander and James Lazell.

Jacket photograph by Ray Matthews.

Jacket design by Lia Camara.

All rights reserved.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available upon request.

ISBN 0-945575-32-7

eISBN 978-1-61620-289-7

Contents

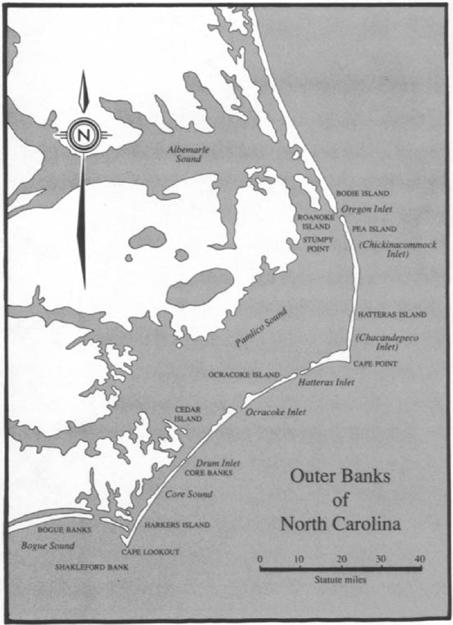

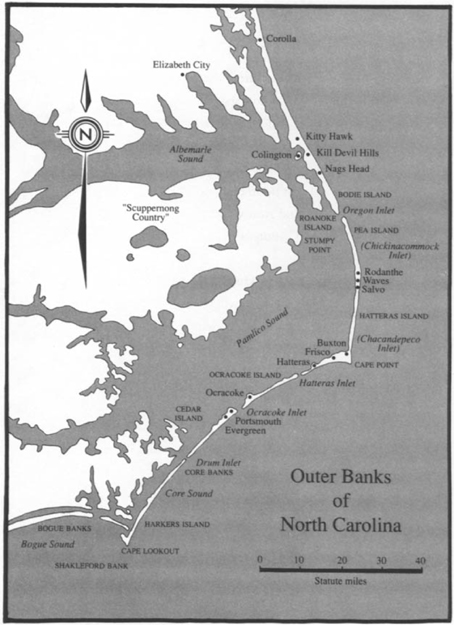

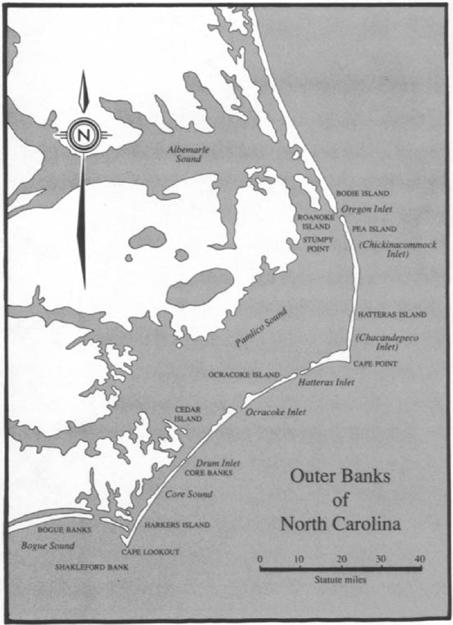

List of Maps and Diagrams

The living inhabitation of the world, the spiritual power of the air, the rocks, the waters, to be in the midst of it, and rejoice and wonder at it, and help it if I could, this was the essential love of Nature in me, this the root of all that I have usefully become, and the light of all that I have rightly learned.

John Ruskin, 1899

Light

flows from the water from sands islands of this horizon

The sea comes toward me across the sea. The sand

moves over the sand in waves

between the guardians of this landscape

the great commemorative statue on one hand

the first flight of man, outside of dream,

seen as stone wing and stainless steel

and at the other hand

banded black-and-white, climbing

the spiral lighthouse.

Muriel Rukeyser, 1980

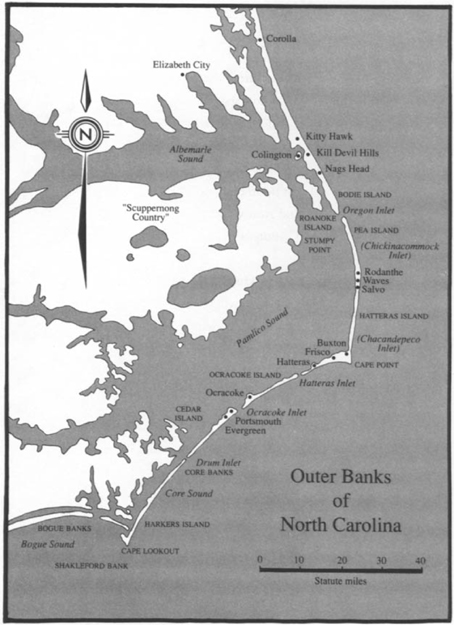

THIS IS A BOOK of connections. Its central character, the connector, the Outer Banks, fringes the eastern edge of our continent. The stories we present here bear the philosophical imprint of John Muir, who saw that ecologically everything is linked to everything else, and of James Burke, author of Connections, who wrote: The reason why each event took place where and when it did is a fascinating mixture of accident, climatic change, genius, craftsmanship, careful observation, ambition and a hundred other factors.

The book has its origins at the University of the South in Sewanee, Tennessee, in 1957, when the authors first began observing and collecting animals together. That friendship and collaboration have spanned more than thirty years, during which we were both drawn to the sands of the Outer Banks in search of an odd kingsnake. Our first joint visit to the Outer Banks occurred in 1972. But it was not until more than fifteen years later that we decided to write this volume.

For their generous support of the research and writing of this book, we are indebted to the Hillsdale Fund and the Mary Norris Preyer Fund of Greensboro, North Carolina; the Prospect Hill Foundation of New York; The Conservation Agency of Rhode Island; the National Park Service; Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill; and our editor, Louis D. Rubin, Jr. And to all who assisted along the waycatching snakes, cleaning fish, rowing boats, and sweeping sandour gratitude.

Chapter One

SAND

And everyone that heareth these sayings of mine, and doeth them not, shall be likened unto a foolish man, which buildeth his house upon the sand: And the rain descended, and the floods came, and the winds blew and beat upon that house; and it fell: and great was the fall of it.

Matthew 7: 26-27

But the sand! The sand is the greatest thing in Kitty Hawk, and soon will be the only thing. The sea has washed and the wind blown millions and millions of loads of sand up in heaps along the coast, completely covering houses and forest.

Orville Wright, 1900

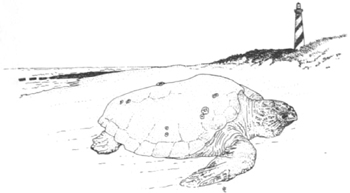

JUNE NIGHT: Cape Hatteras, North Carolina. The Cape Hatteras Lighthouse, beacon to sailors, blinks seaward. With its black-and-white candy-stripe pattern, the lighthouse has proudly symbolized both the romance and terror of the Atlantic for more than a century. The nations oldest and tallest brick lighthouse, it has stood watch over more shipwrecks than any other. But on this night it symbolizes something else: the churlish power of the sea and sand together to humble the grandest human labors, to claim them as surely as it claims a childs sand castle or ghost crabs burrow.

As waves lap ever closer to the lighthouses timber-and-granite base, the brick structure is losing its precarious perch. In due time, according to a schedule that only the ocean keeps, the sand around its footing will begin to wash away. Barring a cumbersome, expensive, engineers scheme to rescue the structure by moving it landward, this stately monumentlittoral leaning towerwill surrender to the seas indifferent embrace.

On this warm June night, however, the lighthouse is not the center of attention: far from it. Mans futile struggle to spare the edifice is only the most conspicuous chapter of a longer epic that has preceded human settlement on the Outer Banks, and that is certain to outlast it. It is an epic of sand, wind, and sea that defines and directs everything that dwells on the Banks, like some epochal operatic production: Aida without the elephants. The difference is that the Banks nonhuman inhabitants must adapt to their environment, or they will die; humans, unthreatened, try to tame it. But the sand, great equalizer, ultimately tames all.

All along Cape Hatteras, a late spring northeaster shoots large, warm, restorative drops of rain. Above the clouds, hidden from the beach a mile north of the lighthouse, a full moon routs the darkness. This is no ordinary night, though the ritual that is about to unfold has played countless times before. On this night, a giant wave blankets the beach along a 100-meter stretch. It is the largest wave in the highest of the months high-course tides. Pushed by the northeast wind (winds are named for the direction they come from), the wave is the largest of the last set at flood tide. Its pounding carries farthest up the beach into the dunes. It contains 4,000 metric tons of water and one-and-a-half million pounds of sand.

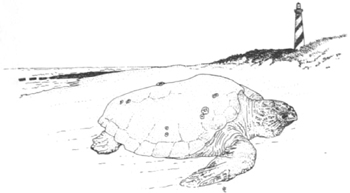

But water and sand are not the waves only cargo. It hauls small animals of the surf zonethe little crustaceans called sand crabs, uncounted and unweighed: imponderable. Also buoyed in its roiling, hissing mass is one ponderous particle: 638 pounds of loggerhead sea turtle. Unlike the sand, the turtle has done everything she can to help the wave move her forward. Her great sculling flippers have scooped into the moving water. Now, with all its curling power, the wave shoves the female forward, disgorging her like excess cargo, wet and not far from the surf. Wet, yes, but as dry as she has been for nearly two years, since the last time she undertook the perilous journey from sea to land.

The peril is as palpable as the warm rain splashing on the turtles barnacled shellperil not so much to the turtle, though human predators still threaten her species survival, but to her burden of round, white eggs. It is not enough that only a small number of the hatchlings gestating in those eggs will ever migrate back to sea. The odds of winning at poker or blackjack are much better.

The threat is more immediate, in the form of a ravenous mother raccoon and her two remaining kits. A third, the weakest, has died already. The raccoons have made their home in an old loblolly pine trunk in the woods west of the lighthouse. It is a spacious den, but these are hard times: too many raccoons. Real summer, just around the corner, will bring people in droves, and people will bring garbage-succulent, mouth-watering quantities of it. For now, there is little to forage, unless the mother raccoons bad luck improves. Unless, for example, she digs for buried treasurea clutch of turtle eggs.

Next page