Table of Contents

DEDICATION

Bear, this is for you.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Allow me to gratefully acknowledge some very large debts.

In the first place, I thank God.

Beyond that, a project like this doesnt come together without the support and help of a lot of people whose names dont show up on the dust cover.

My editors at The Miami Herald have, over the years, been picky, demanding, and difficult to please, and have made me a better writer because of it.

My agent, Janell Walden-Agyeman of Marie Brown and Associates, guided this project from inception to fruition with soft-spoken persistence and unflagging faith.

My family and friends, along with dozens of complete strangers, were gracious enough to open their lives and hearts to the scrutiny of my readers and me.

My wife, Marilyn, has been down with me and up with me for twenty-something years now: my best friend and spiritual advisor, my editor and advocate, my love and my life.

My children, Markise, Monique, Marlon, Bryan, and Onjl, and my grandson, Eric, have taught me that Dad is the finest thing a man can ever hope to become.

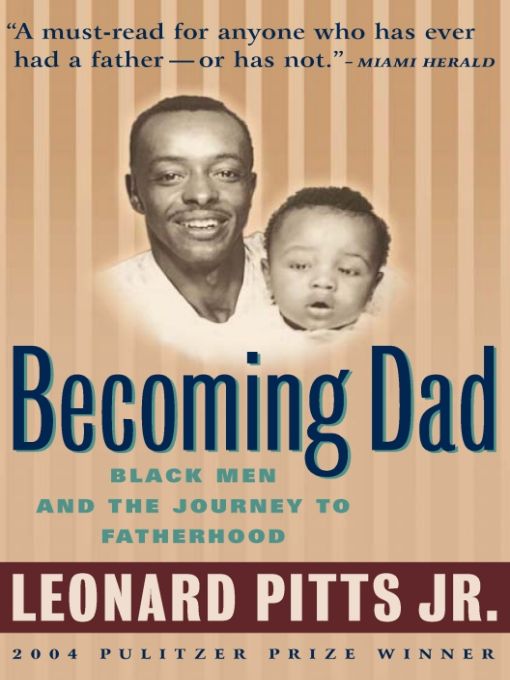

INTRODUCTION

I was unsure about this book when I wrote it.

A book about African-American men who didnt have good fathers struggling to learn how to be fathers themselves? It seemed too specialized for general interest, like a treatise on the mating patterns of the Morro Bay kangaroo rat or the trade routes used by Dutch merchants in the fifteenth century. Who, I wondered, would be able to find value in such a book like this except, wellme?

Son of an abusive alcoholic who may have loved me but definitely didnt like me. Stepfather of two, father of three who challenge my patience, faith, intellect and love every day of every year. Few people, I feared, would be able to relate to any of that, would find value in talking about how it feels to suddenly be a father and to realize, too late, that nothing in your experience has prepared you to know what a father is, even. Nobody else, I thought, would be able to empathize with the idea of watching Cliff Huxtable on The Cosby Show, Ward Cleaver on Leave It To Beaver, Mike Brady on The Brady Bunchany of televisions omniscient, unflappable fathersand seeking not just entertainment, but information. Clues. Lessons in How It Is Supposed to Be. Nobody would understand that.

I was wrong.

I began to realize that shortly after the first hardcover edition of this book came out in May of 1999 and I began to travel around the country to promote it, doing readings and inscribing title pages. There was no eureka moment. Indeed, I couldnt say exactly when the realization dawned.

Maybe it was when the white guy in the black bookstore pulled me aside and told me that my story was his story, too.

Maybe it was when the black woman cop started crying about the beloved stranger who was her father.

Maybe it was when the black man talked about finally growing big enough to grab the arm of the father who had abused himand being shocked at how small it was.

All I know is that at some point in the journey from then until now, I came to realize that my problem was actually our problemmeaning that sad confederation of men (and women) left adrift and bereft by the absence or failure of fathers. There are many of us out here struggling to be something weve never even seen.

And the struggle is crucial, even more crucial than I knew when I wrote this book.

I hesitate to oversimplify complex and difficult problems. But it has become increasingly obvious to me that much of what ails us as African Americans, and us as Americans of whatever heritage, traces from to the simple fact that we have embraced what I will call no-fault fatherhood. Meaning that fathers are allowed to be only tenuously connected to their families, if at all, allowed to be drop-in visitors on their children if they are there at all, with no social stigma attached to this behavior, no sense of failure or shame. No-fault fatherhood is the new normal.

Yet if you look at statistics and studies correlating the presence and involvement of fathers with the tendency of their children to live in poverty, to wind up in jail, to become unmarried parents, and to do poorly in school, you have to grieve that no-fault fatherhood ever came to be. And you have to believe that the solution to much of what ails African America lies in finding a way to reconnect its fathers with its families.

The need is urgent. In the vacuum created by father absence and father failure, popular culture has assumed the role of teacher and lawgiver for too many of our children. Of course, popular culture has always been important as a shaper of culture mores and norms. No child of the Motown era, no black kid who remembers what it was like that first time he saw Shaft, could ever deny this. But pop culture assumes an exaggerated importance in an era when technological advances render it inescapable and parentsfathers specificallycan no longer be counted on to act as a counterweight.

This is especially true given what popular culture made by, for and about young African Americans looks like these days. In a word: coarse. In another word: toxic. Music, television programs and movies targeting our children all too often devolve to hypersexual celebrations of material excess and so-called thug life, whose values are those of the street corner where drugs are sold, life is cheap and morality is relative.

Daily, our children are swamped by a tsunami of swill that validates all the wrong things. They are in need of parentsagain, fathers specificallywho can be depended upon to validate the right things.

But first, a father has to know how to be a father. Perhaps more to the point, he has to know how to become dad.

This book has been out of print for a couple of years now. I get asked about it all the time, though, by men in mentoring groups, by women in churches, by mothers and mothers-in-law eager to nudge sons and sons-in-law toward the recognition of their obligations. I also get asked about it by young fathers who feel that same void Ive felt for the better part of my life. So I am pleased and proud to see Becoming Dad available once again. And I offer it to you with the hope that it will mean more to you than just words on pages. I hope it will be a spur. I hope it will get people talking, and from there, get people acting, encourage them to throw off the self-destructive lie that fathers do not matter.

Because the hour is late and our community is in dire straits, and it is folly to expect a president, a senator or a charismatic leader to come along and make things right. It is time we realized and accepted what is painfully obvious.

We are the salvation of us.

LEONARD PITTS JR.

Athens, Ohio

March, 2006

PART ONE:

Masks and Armor

Papa is a man who can understand

How a man has to do whatever he can.

James Brown

ONE

Im writing a book about black men and fatherhood.

A pause. A dry laugh. And then: What does the one have to do with the other?

The man on the other end of the long-distance connection was himself a black father, an old friend of mine.

Take his response as a warning sign of what a thorny patch one wanders into in any effort to untangle the complexities of black fatherhood. We dont seem to think much of black dads. Theirs is the face we have chosen as an emblem for the failure of fathers, for absence and abuse and a general inability to come to terms with the obligations of paternity.

Next page