Herald Books

Copyright 2016 Miami Herald and el Nuevo Herald. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

Published by Mango Media Inc.

www.mango.bz

No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior written permission.

This is a work of nonfiction adapted from articles and content by journalists of the Miami Herald and el Nuevo Herald published with permission.

Front Cover Image: lassedesignen/Shutterstock.com

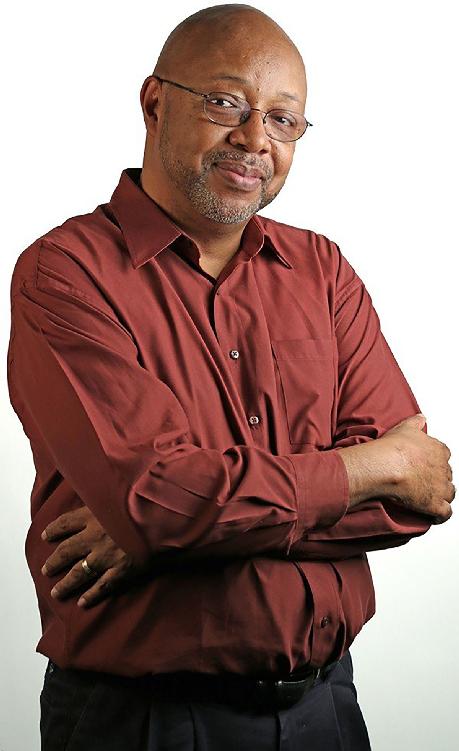

Back Cover Image: Miami Herald

RACISM IN AMERICA:Cultural Codes and Color Lines in the 21stCentury

ISBN: 978-1-63353-446-9

Race is the stupidest idea in history. It is also, arguably, the most powerful. It determines who goes to jail and who goes to college, who gets loans and who gets rejections, who gets the job and who gets the unemployment check. It determines the life you live and the assumptions that are made about you.

Leonard Pitts, Jr., December 30, 2012

Table of Contents

INTRODUCTION

Sunday, December 30, 2012

RACE

On New Year's Day, it will be 150 years since Abraham Lincoln set black people free from slavery.

And there is no such thing as black people.

The first of those statements is not precisely true; a clarification will be offered momentarily. The second statement is not precisely false. And the clarification begins here:

It is a clarification needed not simply because it helps us to better understand the milestone of history we commemorate this week, but also because it helps us to better understand America right here in the tumultuous now. The Republican Party, to take an example not quite at random, enters the new year still nursing its wounds after an election debacle most observers laid upon its inability to sway Hispanics, young voters and, yes, black people. Then there is the Trayvon Martin shooting, the mass incarceration phenomenon, the birther foolishness.

A century and a half later, in other words, race is still a story. Black people are still a story.

How can that be, if there is no such thing as black people?

Granted, most of us think otherwise. The average 18-year-old American kid, says sociologist Matt Wray, thinks of race "as a set of facts about who people are, which is somehow tied to blood and biology and ancestry."

But that kid is wrong. If you doubt that, try a simple challenge: Define "black people."

Maybe you think of it as African ancestry. But Africa is a place on a map not a bloodline. And, as the example of Charlize Theron, the fair-skinned, blond actress from South Africa, amply illustrates, it is entirely possible to come from there, yet not be what we think of as "black." Indeed, Theron, who became a naturalized U.S. citizen in 2008, is by definition an African American. Yet, she fits no one's conception of that term, either.

Or, you might define "black people" by physical appearance: i.e., people with dark skin and coarse hair. If so, consider Gregory Howard Williams, a pale-skinned American educator and author of the memoir Life On The Color Line, who did not learn he was "black" until he was 10. Or consider Walter White, the former executive secretary of the NAACP, whose 1948 autobiography begins: "I am a Negro. My skin is white, my eyes are blue, my hair is blond." Consider the people from India who have dark skin or the ones from Asia, the Middle East or Latin America who have coarse hair.

And perhaps here, you are tempted to throw up your hands and paraphrase Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart who famously said of pornography that he might not be able to define it, "but I know it when I see it."

The difference is that pornography, at least, exists. But there is no such thing as black people. Or white people. Or Asians. Or Indians.

What is my point? It's simply this: Race is the stupidest idea in history.

Or, as Wray puts it, "race was a big mistake."

To which Nell Irwin Painter adds the observation that a decade of research and writing on the subject taught her "that if you try to consider race as a real thing, it makes no sense."

Wray, a Temple University professor and the author of Not Quite White: White Trash and the Boundaries of Whiteness, and Painter, a former professor at Princeton and the author of The History of White People, are leading lights in a burgeoning field of study whose aim is nothing less than the deconstruction of race. It seeks to answer the question of when, how, and why we ever got it into our heads there is such a thing as race; when, how, and why we decided we could divide human beings into subgroups whose members all shared similar traits and that those subgroups could be ranked, superior to inferior.

The "when," as it turns out, is pretty easy to answer, though the answer is surprising, in light of how conditioned we are to think of race as something that always was and always will be. The concept of race, says Painter, dates from about the mid-18th century. It is less than 300 years old.

Though there were always a few people, she says, who attempted to impute character or worth from a stranger's color, it was more likely in that era for people to make those judgments based upon a stranger's religion or wealth. "So if you were a light-skinned person and you met a dark-skinned person in rags, and you weren't [in rags], you'd feel superior," says Painter. "But if you were in rags and that other person was in rags, you'd be trying to figure if that person had something that you could get."

Then came race that which would allow one person in rags to feel superior to another person in rags. Early on, it was defined not by appearance but as a function of climate. Greek scholars believed people from places where the seasons do not change were placid. Those from places of dramatic seasonal shifts were wild and unsociable. Those from hot places were impulsive and hot-tempered. Those from cooler climes were stiff and intellectual.

Race was also defined geographically. Hippocrates, the great Greek physician, thought people who lived in low-lying areas tended to be dark-skinned, fat, cowardly, ill-spoken and lazy. Those who lived in flat, windy places would be large in stature, "but their minds will be rather unmanly and gentle."

And then, there were those who decided the key to race lay in measuring the size and shape of people's skulls.

"American scientists and anthropologists get ahold of this concept by the early 1800s," says Wray. "For the whole of the 19th century, they're refining and tweaking their models to really give scientific weight and authority to the notion that these racial differences can be empirically verified. In other words, they're out there in the world. We just have to figure out whether it's the distance between the eye sockets and the bridge of the nose, or some combination of measurements from the back of the skull to the chin divided by the circumference of the head that will give us the kind of golden ratio we're looking for in other words, the one that will enable us to definitively say, this person is African, this person is Caucasian and so forth."