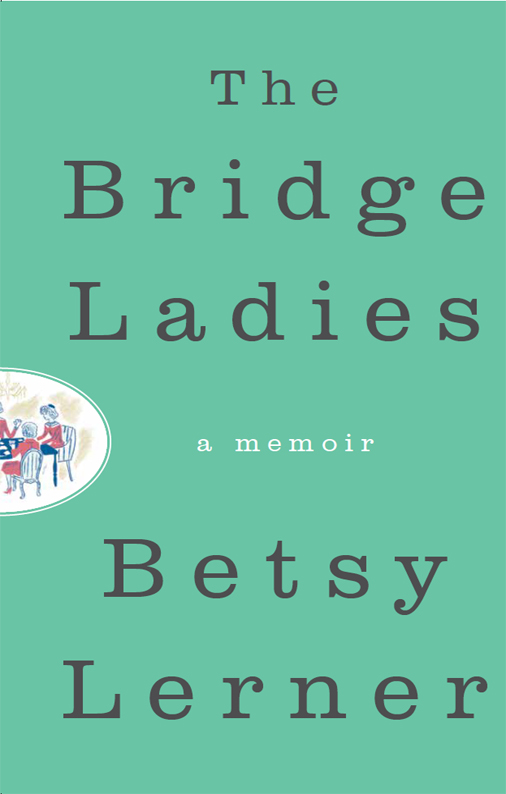

As a child, I was fascinated with the Bridge Ladies. They showed up regularly at our house, their hair frosted, their nylons shimmery, carrying patent leather pocketbooks with clasps as round as marbles. I loved greeting them at the door, hanging up their coats in our front hall closet, where I often played inside the folds of my mothers mink. I watched as they gathered around the card table, crowded with a twinset of cards, ashtrays, cellophane-wrapped cigarette packs, a scoring pad, and crystal dishes of candy. Eye level to the Bridge table, I greedily surveyed the candy and would plan high-speed kamikaze raids to nab some from below my mothers radar. Where my father would let me sit on his lap while he played Gin Rummy for a hand or two, the Bridge Ladies erected a square fortress with their backs as they played, communing in their strange language of bids and tricks.

As a teenager, Id make myself scarce when the Bridge Ladies came over. As far as I was concerned, they were square. They didnt work, didnt seem to get that feminism was taking over the world. Billie Jean King had defeated Bobby Riggs in the Battle of the Sexes Tennis Match, Gloria Steinem had started Ms. magazine, and Helen Reddy roared. To me, the Bridge Ladies were conventional, their sphere limited to family, synagogue, and community. Their identities restricted to daughter, mother, and wife. On top of which their idea of fun was an afternoon of playing Bridge. Seriously?

I was after bigger game. I was already reading Anas Nin and Henry Miller. In other words, I was determined to lose my virginity as soon as possible and have many lovers. I hated our New Haven suburb and my high school for its devotion to conformity. As far as I could tell, the most creative endeavor for the girls was growing their hair as long as possible in order to qualify for the national Long & Silky contest. All I wanted to do was get out and stay out. I spent my time dreaming of escape to New York, specifically Greenwich Village, where I hoped to find like-minded people, poets, and writers. I moved there for college and stayed for graduate school. Though I didnt become a fixture at Studio 54 or Warhols Factory, Id made a life there: worked in publishing, eventually married, and had a daughter.

Then something happened. After twenty years of living and working in New York, my husband was offered a job at Yale University Press. You didnt need a Google map to see where this was going: New Haven, my childhood home and the crucible of my pain. I was supportive when he accepted the job; the reality of moving home took a little longer to fathom.

For me, the biggest challenge was having my mother become a regular part of our lives. When I lived in New York, we spoke once a week, perfunctorily on Sundays. Now I would be living 5.1 miles away from her. I told myself I could handle it. After all, I was well into my forties when we moved home, I was a mother in my own right, yet my conflicts with my mother still flared brightly. Why was everything so loaded? Why was I reduced to my teenage self almost every time we got together? Was everything she said a criticism, or did it only sound that way? We circled each other like wary boxers. Once, she asked why I bought low-fat cottage cheese instead of fat-free and nearly set off a world war between us. It was cottage cheese, for gods sake! Translated through the mother-daughter lexicon: Was I ever going to be good enough?

When my mother was recovering from some surgery in January of 2013, I stayed with her to help out. We had been living in New Haven for more than a decade by then, my dad gone, my daughter a teenager in her own right, we had made new friends and were knitted in. I had become a partner in a literary agency and was commuting to New York twice a week, getting my city fix. On top of that, God shined down his light on our fair city and conferred an Apple Store upon us. Did I really have any reason to complain?

I wasnt exactly looking forward to staying with my mother, but I also knew the job would be made less onerous by the fact that she, even at eighty-three, was more comfortable refusing help than demanding it, best summed up in the well-known joke: How many Jewish grandmothers does it take to screw in a lightbulb? You shouldnt worry... Ill sit in the dark.

Every day, one of her Bridge Ladies visited, as if in an unspoken rotation. They were smaller now, some a little unsteady, but still decked out in color-coordinated outfits, accessories, heels, and bags. When they said I looked good, I wondered if they really thought I was fat, if my unruly hair was an offense. When they asked after my husband and daughter, it struck me that they had been there for all of the rites of passage in my life: they had attended my bat mitzvah, danced at my wedding, and sent gifts when my daughter was born. I had never really taken stock of their generosity; they likely had no idea how much adolescent rancor and disrespect I harbored. Or how I had clumped them all together like the presidents carved into Mount Rushmore, indistinguishable one from another.

As demographics go, the Bridge Ladies couldnt be more alike. They are all in their eighties, all Jewish, and they all attended college. They married young, married Jewish men, and stayed married to them. They had 2.5 children. None worked outside the home during the years they raised their children, except Rhoda, who shattered the stained-glass ceiling when she became the executive director at the synagogue. They did the shopping and cooked the meals; The Joy of Cooking, published in 1936, was their bible. They picked up the dry cleaning and cleaned their homes. (Eventually, each would be able to afford cleaning ladies, as they would all become upwardly mobile.) They decorated and planned vacations, from the Catskills to Puerto Rico to Rome.

They lived through the Depression and World War II. Some of their husbands joined the war effort. They witnessed the civil rights era, The Vietnam War, and the feminist movement, though they didnt shed their girdles or burn their bras. They were just a little too old or insulated to embrace The Feminine Mystique or articulate the problem that had no name. They saw interfaith marriage among their children and interracial marriage among their grandchildren. When they grew up, gay people were completely closeted, like movie star heroes Montgomery Clift and Rock Hudson. Today, they are witness to the legalization of gay marriage in every state in the nation.

Though they were not all born in New Haven, they have lived in the greater New Haven area for all of their adult lives, they raised their children here, four have buried husbands here, and one buried a daughter. They are all in relatively good health (knock on wood, poo poo poo). Their adult children are as great a source of pride as they are of aggravation. They dont like to brag, but their grandchildren are brilliant. And on Mondays at noontime, for the past fifty-five years, they gather for lunch and Bridge, the card game whose golden age coincided with their generations coming of age.

Bridge was the HBO of its day. In the 1930s and 1940s, 44 percent of American households had at least one Bridge player. Matches were broadcast on radios, and popular movies like Sunset Boulevard and Shadow of the Thin Man featured scenes with Bridge games. Robert Cohn, a character in Hemingways