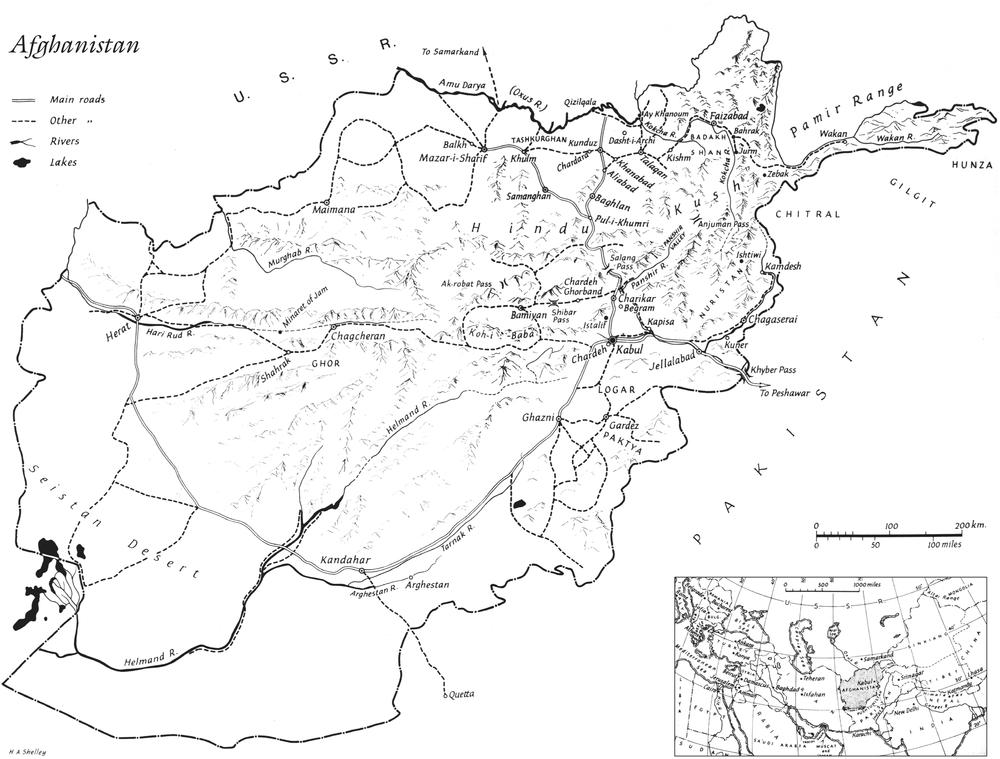

W hen all this started, I was a young Jesuit priest of fairly good repute, a classical scholar with a teaching post at Oxford. So long has gone by since 1968 that I now need to write a new introduction to the book. All the same, the idea of going to Afghanistan was not as strange in the nineteen sixties as it has been since the Russian invasion, which readers will observe was already expected in my day. Now of course the valleys have been napalmed, my friends are dead, only the archaeologists survived and have moved on. The French excavator of Ay Khanoum whose lecture in Oxford first excited me is digging this year at Samarkand. I was not alone in being attracted by the strange story of a Greek site in so remote a part of the world, first identified by the King, who was eating his lunch on a hunting trip, sitting on a Corinthian capital; he sensibly called in the French.

In those days the British had not begun their operations at Kandahar, abandoned now, though the Italians were at work at Ghazni and in Seistan and in Sir Aurel Steins old stamping ground, the Tribal Territories of Pakistan. Ay Khanoum was the first of Alexander the Greats eastern frontier cities to be seriously excavated, because the others, which were chosen by the Greeks for their usefulness as fortresses, were all still in use. But at Ay Khanoum the River Kokcha flowed down into the Oxus, down from the mountains where lapis lazuli was mined, and Balas rubies and rock crystal were as easy to find as fossils are at Lyme Regis. It was a fortress for defence and a trading post, and the worlds only source of lapis lazuli until the discovery of Latin America. The deep blue colour was used to make Durham manuscripts; it came from that abandoned place, Persian before it was Greek, and still not far from the Chinese border.

It interested me, though I picked it almost at random for its romantic side. I had not then read Kiplings Man who would be King, and the film had not been made, but I greatly admired Sir Aurel Stein; I had just finished writing the Penguin commentary on Pausaniass Guide to Greece, and I wanted to look at some Greek archaeology outside mainland Greece. I felt I had a year or so to play with; for the future I was attracted by the classicism of Angkor Wat, but that was still a step too far. I felt it better to establish what I could about any classical influences on Buddhist architecture and sculpture, before straying so far across the icy deserts. Of course the road not taken is always the one you want to go back to, and the sight of a lapis lazuli hoop on the head of a Chinese prince I saw a few years later in Paris (and again in London) still disturbs me deeply.

In order to go to Afghanistan I would have to write a book with a trusting publisher to pay the expenses. I think the advance was two or three thousand pounds. I had of course tried the alternative of applying to those who gave grants, but from them I experienced no such generosity. I did not know Persian, and the only Afghan I knew personally was someone I had once had lunch with in Oxford. I was introduced to him as the next King, but he turned out to be only Daouds son, the Kings cousin once removed, who became an innocent Professor of History at Kabul University. I tried a number of friends but none of them was both free and willing to come with me, and if I must write a book the expedition must take a serious length of time. John Prag, now a Professor at Manchester and Director of the classical museum, nearly came but had to cry off. It was he who told me to read Eric Newbys A Short Walk in the Hindu Kush, a book as brilliant and inspiring as it was daunting, since his expedition lasted just a fortnight.

I knew that I could get on with John, since we had lived together in a shed in Libya with a railway engine that woke us only once a week, when it issued forth furious among clouds of steam, to shift sand on a miniature railway around the ancient city of Tocra, where we were excavating as apprentices the Spartan colony on the edge of land between the sea and the desert. John Boardman was director and we found what we were after, because luckily the Romans had dug a channel for boats, leaving the sixth century BC material from the bottom of their trench on the surface. I do not remember much about what we found, except an Italian regimental hat-badge and a pop record of the thirties, broken of course. There was a girl who I think became a Byzantinist, whose favourite food was cold tinned peas. I had to go home early, and nearly died on the way, since I turned out to have contracted blood-poisoning from a dirty needle at Athens airport. This story does not give one much confidence about the Afghan expedition.

Bruce Chatwin was in many ways the ideal companion: he was wonderfully entertaining and as a liar he outdid the Odyssey, but he was also deadly serious. I had known him for years, as a Sothebys salesman or expert, and then, when he gave that up, as a student of my revered friend Stuart Piggot in Edinburgh. Bruce gave up Sothebys because it was driving him mad, and he was suffering attacks of blindness which are a kind of hysteria: anyway the money bored him. He gave up archaeology because lectures at Edinburgh were compulsory and the students stank. He also could not stand being told there are no works of art, only artefacts. He now thought of writing a vast thesis of a book about nomads and the urge to wander. He did in fact finish it in the end, but then under the quasi-magical influence of a girl who disliked the footnotes, he flung it into the fire and started again. His road towards becoming a writer was a long one, and it was only in Songlines that he made use of the notes that had once been the foundation of his nomad studies.

However that may be, his story of the tramp he met in Jermyn Street was then fresh, and he wanted to go back to Afghanistan, where he had already been twice, to see the nomads walking up and down as he used to quote from Robert Burton, and luckily I suggested the journey to him one day in the Ashmolean Museum, where we both used to read. I was surprised and delighted when he agreed. I got us diplomatic visas through a Foreign Office friend, which turned out to be vital, and as soon as Oxford term was over, I was ready to be off. I had no qualms about travelling with Bruce. I had met him first as a friend of Tony Mitchells on an expedition to Blockley to see the antiquities collection of that formidable eccentric, Captain Spencer-Churchill, Winstons first cousin, who had bought the necklace of an Egyptian Queen from the German consul in Luxor in 1905 for five pounds and had never stopped collecting ever since. We were in two cars, one of them an old fixed axle racing car, which ended up a tree, teetering over a ten foot drop.

We had our disadvantages: Bruce was married but I did not know Elizabeth, and it did not occur to me that he was homosexual, or that it was any business of mine if he were. I was then a Jesuit priest, but it had not occurred to me that I would not be able to say Mass in Afghanistan. Bruce turned out to be a hypochondriac with some experience of diseases and treatments, from which I benefited greatly. His exaggerations were reserved for romantic subjects where the truth would be no use anyway. When he said had I seen the animal droppings on a path through the woods, and warned me his wife had pondered them doubtfully and was always right about such things, they turned out to be a snow leopards. That was a practical, not a romantic matter. He was a charming guest to Chris Rundle, whom we met at the Embassy in Kabul and who took us in out of the kindness of his heart, because he had seen me as Yevtushenkos translator in Oxford. He became a friend and a companion of our best journey, being the most modest and reliable of men, and his house in the Embassy grounds was a refuge as fortunate for us as Corfu was to Odysseus. He was one of the last Oriental Secretaries left, who knew Persian as well as Russian, seconded from the research department of the Foreign Office, where his job was reading newspapers. He found a wife in Afghanistan a few years later and took her home with him.