Maugham - A Writers Notebook

Here you can read online Maugham - A Writers Notebook full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: London, year: 2011, publisher: Random House;Vintage Digital, genre: Art. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:A Writers Notebook

- Author:

- Publisher:Random House;Vintage Digital

- Genre:

- Year:2011

- City:London

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Writers Notebook: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "A Writers Notebook" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

From 1892, when he was eighteen, until 1949, when this book was first published, Somerset Maugham kept a notebook. It is without doubt one of his most important works. Part autobiographical, part confessional, packed with observations, confidences, experiments and jottings it is a rich and exhilarating admission into this great writers workshop

A Writers Notebook — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "A Writers Notebook" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

From 1892, when he was eighteen, until 1949, when this book was first published, Somerset Maugham kept a notebook. It is without doubt one of his most important works. Part autobiographical, part confessional, packed with observations, confidences, experiments and jottings, it is a rich and exhilarating admission into this great writers workshop.

W. Somerset Maugham

N OTEBOOK

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author's and publisher's rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Version 1.0

Epub ISBN 9781407074771

www.randomhouse.co.uk

Published by Vintage 2001

2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1

Copyright The Royal Literary Fund

First published in Great Britain in 1949 by William Heinemann

Vintage

Random House, 20 Vauxhall Bridge Road,

London SW1V2 SA

The Random House Group Limited Reg. No. 954009

www.randomhouse.co.uk

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

In loving memory of my friend

Frederick Gerald Haxton

18921944

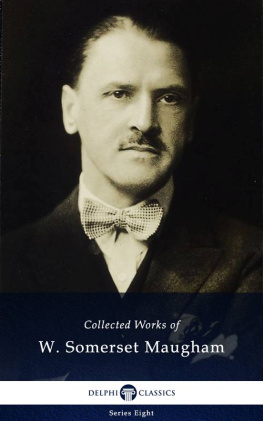

William Somerset Maugham was born in 1874 and lived in Paris until he was ten. He was educated at Kings School, Canterbury, and at Heidelberg University. He spent some time at St. Thomass Hospital with the idea of practising medicine, but the success of his first novel, Liza of Lambeth, published in 1897, won him over to letters. Of Human Bondage, the first of his masterpieces, came out in 1915, and with the publication in 1919 of The Moon and Sixpence his reputation as a novelist was established. His position as a successful playwright was being consolidated at the same time. His first play, A Man of Honour, was followed by a series of successes just before and after World War I, and his career in the theatre did not end until 1933 with Sheppey.

His fame as a short story writer began with The Trembling of a Leaf, subtitled Little Stories of the South Sea Islands, in 1921, after which he published more than ten collections. His other works include travel books such as On a Chinese Screen and Don Fernando, essays, criticism, and the autobiographical The Summing Up and A Writers Notebook.

In 1927 Somerset Maugham settled in the South of France and lived there until his death in 1965.

ALSO BY W. SOMERSET MAUGHAM

Of Human Bondage

The Moon and Sixpence

The Narrow Corner

The Razors Edge

Cakes and Ale

The Summing Up

Collected Short Stories Vol. 1

Collected Short Stories Vol. 2

Collected Short Stories Vol. 3

Collected Short Stories Vol. 4

Ashenden

Far Eastern Tales

More Far Eastern Tales

South Sea Tales

For Services Rendered

The Merry-Go-Round

Don Fernando

On a Chinese Screen

The Painted Veil

Catalina

Up at the Villa

Mrs Craddock

Liza of Lambeth

Ten Novels and their Authors

The Casuarina Tree

Christmas Holiday

The Magician

Points of View

Selected Plays

Theatre

Then and Now

The Vagrant Mood

The Journal of Jules Renard is one of the minor masterpieces of French literature. He wrote three or four one-act plays, which were neither very good nor very bad; they neither amuse you much nor move you much, but when well acted they can be sat through without ennui. He wrote several novels, of which one, Poil de Carotte, was very successful. It is the story of his own childhood, the story of a little uncouth boy whose harsh and unnatural mother leads him a wretched life. Renards method of writing, without ornament, without emphasis, heightens the pathos of the dreadful tale, and the poor lads sufferings, mitigated by no pale ray of hope, are heartrending. You laugh wryly at his clumsy efforts to ingratiate himself with that demon of a woman and you feel his humiliations, you resent his unmerited punishments, as though they were your own. It would be an ill-conditioned person who did not feel his blood boil at the infliction of such malignant cruelty. It is not a book that you can easily forget.

Jules Renards other novels are of no great consequence. They are either fragments of autobiography or are compiled from the careful notes he took of people with whom he was thrown into close contact, and can hardly be counted as novels at all. He was so devoid of the creative power that one wonders why he ever became a writer. He had no invention to heighten the point of an incident or even to give a pattern to his acute observations. He collected facts; but a novel cannot be made of facts alone; in themselves they are dead things. Their use is to develop an idea or illustrate a theme, and the novelist not only has the right to change them to suit his purpose, to stress them or leave them in shadow, but is under the necessity of doing so. It is true that Jules Renard had his theories; he asserted that his object was merely to state, leaving the reader to write his own novel, as it were, on the data presented to him, and that to attempt to do anything else was literary fudge. But I am always suspicious of a novelists theories; I have never known them to be anything other than a justification of his own shortcomings. So a writer who has no gift for the contrivance of a plausible story will tell you that story-telling is the least important part of the novelists equipment, and if he is devoid of humour he will moan that humour is the death of fiction. In order to give the glow of life to brute fact it must be transmuted by passion, and so the only good novel Jules Renard wrote was when the passion of self-pity and the hatred he felt for his mother charged his recollections of his unhappy childhood with venom.

I surmise that he would be already forgotten but for the publication after his death of the diary that he kept assiduously for twenty years. It is a remarkable work. He knew a number of persons who were important in the literary and theatrical world of his day, actors like Sarah Bernhardt and Lucien Guitry, authors like Rostand and Capus, and he relates his various encounters with them with an admirable but caustic vivacity. Here his keen powers of observation were of service to him. But though his portraits have verisimilitude, and the lively conversation of those clever people has an authentic ring, you must have, perhaps, some knowledge of the world of Paris in the last few years of the nineteenth century and the first few years of the twentieth, either personal knowledge or knowledge by hearsay, really to appreciate these parts of the journal. His fellow writers were indignant when the work was issued and they discovered with what acrimony he had written of them. The picture he paints of the literary life of his day is savage. They say dog does not bite dog. That is not true of men of letters in France. In England, I think, men of letters bother but little with one another. They do not live in one anothers pockets as French authors do; they meet, indeed, infrequently, and then as likely as not by chance. I remember one author saying to me years ago: I prefer to live with my raw material. They do not even read one another very much. On one occasion, an American critic came to England to interview a number of distinguished writers on the state of English literature, and gave up his project when he discovered that a very eminent novelist, the first one he saw, had never read a single book of Kiplings. English writers judge their fellow craftsmen; one they will tell you is pretty good, another they will say is no great shakes, but their enthusiasm for the former seldom reaches fever-heat, and their disesteem for the latter is manifested rather by indifference than by detraction. They do not particularly envy someone elses success, and when it is obviously unmerited, it moves them to laughter rather than to wrath. I think English authors are self-centred. They are, perhaps, as vain as any others, but their vanity is satisfied by the appreciation of a private circle. They are not inordinately affected by adverse criticism, and with one or two exceptions do not go out of their way to ingratiate themselves with the reviewers. They live and let live.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «A Writers Notebook»

Look at similar books to A Writers Notebook. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book A Writers Notebook and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.