Table of Contents

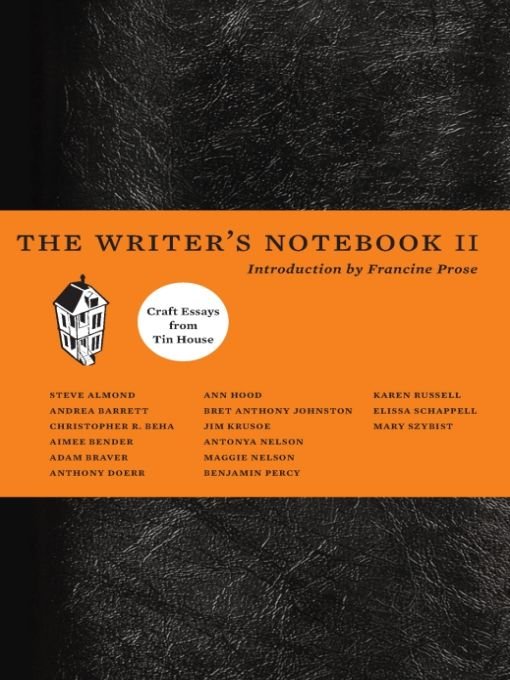

Craft Essays from Tin House

INTRODUCTION

FRANCINE PROSE

WHY SHOULD IT seem surprising that if we want to know what writers thinkreally thinkabout writing, we should read more of what they write and listen less to what they say? Having been a speaker, an audience member, an interviewer and an interviewee at the question-and-answer sessions that so often follow literary readings and panels, I have witnessed, and been responsible for, those moments when a writer takes the easy way out and simply repeats a facile statement shes made before, or blurts out something to fill the silence, whether or not its true.

Writers are creatures who (to paraphrase Wordsworth) function best when we can recall the writing process in tranquility. Which isnt to say that the experience of sitting in front of the blank page or screen is necessarily a tranquil one, unless you are the sort of masochist who finds peace in hideous anguish. Still, the closest writers may ever come to saying something accurate, let alone useful, about what we do is when we are alone, at our desks, in privatewhen we write the sort of essays collected in The Writers Notebook II.

I think its probably safe to say that most writers would rather lose themselves in a story or a poem than remain in the prison of their conscious selves and attempt to describe what we do. And though most writers would rather write a story or a poem than an essay about writing a story or a poem, the fact is that we are occasionallythanks to teaching or lecture commitments, a deadline or an invitationmoved to think about this bizarre activity that is at once our lifes blood and our job.

Nor should it come as a great surprise that writers can actually write, even when they are writing about writing. Each of the essays in this collection finds its unique voice in the way that each author chooses to place one word after anothervocabulary and punctuation decisions, matters of tone and diction, of perspective, detail, and length. The way in which these essays are written are lessons in themselves, lessons that reach us, above and beyond the substance of what their authors are saying.

You can open The Writers Notebook II at random and find some sentence that will surprise or delight you, a phrase or paragraph that will make you think, or laugh out loud. Or both. Here is Elissa Schappell on what may be the all-time worst ending in the history of fiction: There is a tale, now legendary in the circles of teachers of creative writing, about a story that ends with the revelation that the story was being narrated by a squirrel with a bag on its head. And Steve Almond on a young writers desire to be taken seriously: If enough people took me seriously I might start to take myself seriously, thereby dispelling the notion, forever lurking at the gates of ambition, that I was a sad clown who should quit writing and return to my given career as a professional masturbator, a career for which I am even now somewhat nostalgic. And listen to Karen Russell on the richness with which literature excites and satisfies a childs imagination: As a kid growing up in Miami, I lived in the closet of my mind, trying on costumes... I wanted scales and wings. Id figured out that you could do these really bizarre tricks in the library, in full view of the imperturbably cheerful librarians. You could, for example, metamorphose. You could suture a characters wings to your eight-year-old body. You could drop time like a skirt and step outside its wrinkled orbit.

If one had to find a common thread stitched through all, or most, of these intensely individual essays, it might wind its way around the question of how much writers readand how much inspiration they take from the work of their predecessors. Maggie Nelson pays tribute to the poetry of Alice Notley and Anne Carson; Mary Szybist contributes thoughtful and perceptive readings of Emily Dickinson and John Ashbery; Jim Krusoe views an array of literary masterpieces through the lens of the dream; Bret Anthony Johnston examines the magic with which Tim OBrien and Lorrie Moore alchemize experience into art; Ann Hood takes us on a lively tour of introductory sentences, from the familiar beginnings of Anna Karenina and Pride and Prejudice to the less often quoted but no less arresting introductions to Mrs. Dalloway and Elmer Gantry. Anthony Doerr looks to Camuss novel The Stranger and to Joyce Carol Oatess story Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been? for instructionwhich he kindly passes on to usin how to build and maintain suspense. And Christopher R. Beha transcribes an extraordinarily beautiful and useful passage from Saint Augustine about, as Beha puts it, the beauty to be found in a well-made whole.

Much of what any writer needs to know is contained in this helpful book. Andrea Barrett muses on the pleasures of research, the challenges and rewards of incorporating history into ones work. Benjamin Percy considers the importance of work itselfthe jobs that people do: Writing is an act of empathy. You are occupying and understanding a point of view that might be alien to your ownand work is often the keyhole through which you peer. Adam Braver describes the experience of editing a manuscript with the aid of a pair of scissors and a roll of Scotch tape. Antonya Nelson comes as close as anyone ever has to describing how sheor anyonewrites as she tells us about a class in which she asked her students to undertake the process of writing that I myself undertake.

In her essay On the Making of Orchards, Aimee Bender quotes a line from Dante suggesting that art is Gods grandchild. After finishing the last of these essays, we may all feel a little closer to being the distant relatives of art or nature or God. Reading The Writers Notebook II is like spending a couple of hours or days or weeks in the company of writers whose voices you want in your head, whose words you want to keep beside your desk. Go ahead, they seem to be saying. Here is how writing has been for me, and this is what Ive learned. Consider this, think about that, read the books that have inspired me. Im going to tell you what I know, but the rest is up to you. All you have to do now is just sit downand begin.

BEGINNINGS

ANN HOOD

I CANNOT WRITE an essay, a short story, or even a novel until I know my first line. At night, I put myself to sleep rearranging words, inserting a comma and then taking it out again. I edit and revise that one sentence while I cook dinner, wait in the car for my kids to walk out of school, do the laundry. The pressure of getting that sentence right is enormous. In fact, not just that sentence, but the opening paragraphno, the opening pagehas to do so much that in some ways it is the most important thing to write.

The beginning introduces the protagonist and his or her conflict. It creates tone, point of view, setting, voice. It introduces themes. Or, as Ted Kooser explains in The Poetry Home Repair Manual, the opening is the hand you extend to your reader. When the writer John Irving told me that he always knew his first line before he began writing, because by knowing his first line he then knew his last line, I understood yet another burden of the beginning: it puts into motion the events that will drive the story to its resolution. And that resolution is often the inverse of the opening.